Translate this page into:

Seroprevalence of transfusion transmitted infections in healthy blood donors: A 5-year Tertiary Care Hospital experience

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sushama A. Chandekar, Flat No. 33, Building No. 1, Government Coloney, K. K. Marg, Haji Ali, Mumbai - 400 034, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: sushamachandekar@rediffmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Transfusion transmitted infections (TTIs) can cause threat to bloody safety as blood transfusion is an important mode of transmission of TTI to the recipient, hence, to prevent transmission of these diseases, screening tests on blood bags is an important step for blood safety.

AIM:

This study was undertaken with the aim of determining the seroprevalence of TTI in healthy blood donors in a tertiary care blood bank.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A retrospective study was carried out over a period of 5 years from January 2007 to December 2011. Serum samples were screened for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Type 1 and 2, hepatitis c virus (HCV) and syphilis using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with the third generation kits and venereal disease research laboratory test, respectively.

RESULTS:

A total of 76,653 healthy donors were included out of which majority of donors were male (91.79%). The overall seroprevalence of HIV, HBsAg, HCV, and syphilis were 0.26%, 1.30%, 0.25%, and 0.28%, respectively.

CONCLUSION:

Methods to ensure a safety blood supply should be encouraged. For that, screening with a better selection of donors and use of sensitive screening tests including nucleic acid testing technology should be implemented.

Keywords

Hepatitis B virus

hepatitis C virus

human immunodeficiency virus

seroprevalence

transfusion transmitted infections

Introduction

Blood safety is of utmost importance in transfusion medicine. Transfusion-transmitted infections (TTIs) hamper blood safety and cause a serious public health problem.[1] A person can transmit an infection during its asymptomatic phase and so transfusion can contribute to an increase of infection in the population. Unsafe blood transfusion proves very costly for both the recipient and society at large. Screening TTI is also essential for blood transfusion safety and for protecting human life.[2] Blood transfusion is a life-saving procedure but can cause acute and delayed complications. Blood donors are the resources of a safe supply of blood and blood products.[3] Complications of blood transfusions may be mild or can be life-threatening and hence meticulous pretransfusion testing and screening for transfusion-transmissible infections is mandatory.[4] These infections are a threat to blood safety, and so blood transfusion services have to ensure safe, adequate, accessible, and efficient blood supply at all levels. All these transfusion transmissible infections cause prolonged viremia and carrier or latent state. These infections also cause fatal, chronic, and life-threatening disorders. The TTI's include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis c virus (HCV) and syphilis. 12.5% of patients who received blood transfusion are at risk of posttransfusion hepatitis.[5] To reduce risk of TTIs, careful selection of donors is needed so that the blood is safe and is not collected from the people who are likely to be carriers of infectious agents. Evaluations of TTI are essential for assessing the safety of blood supply and monitoring the efficiency of currently employed screening procedures.[6] The present study was carried out with the aim of determining the seroprevalence of TTI among healthy blood donors in a tertiary care hospital.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study was carried out at our institution where data were analyzed over a period of 5 years from January 2007 to December 2011. Blood was collected from apparently healthy individuals after detail history and examination, aged 18–60 years with weight >45 kg with hemoglobin concentration >12.5 gm%. All blood donors' samples were screened for HIV, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), HCV, and syphilis. Blood bank donor cards were used as a source of information. HIV, HBsAg, HCV tests were done by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) procedure using the third generation kits. Syphilis was diagnosed by performing the venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. Malaria testing was done by slide method using Leishman's staining. Blood donors were selected if they fulfilled all the criteria to be eligible for donation as described by the standard operating procedure of our blood bank.

Blood sampling

Venous blood was collected in plain vacutainer tubes which was allowed to clot naturally at room temperature. The clotted blood sample in plain vacutainer tubes was then spun in a centrifuge machine at 2500 rpm for 5 min to separate the serum which was further used for serological analysis. Hemoglobin determination was done by the traditional CuSO4 method. Tests on donor blood were carried out according to manufacturer's instructions with positive and negative controls. Before drawing the blood, each donor was requested to fill blood donor's card. Blood samples were tested, and reactive sera were confirmed by repeat testing using another kit manufactured by the different company. Confidentiality of reports was maintained as per standard guidelines.

Human immunodeficiency virus serology

Microlisa HIV (J. Mitra and Co., Pvt., Ltd.,) kits were used for detection of antibodies to HIV-1 (including subgroups O and C) and HIV-2. The Microlisa test is an enzyme immunoassay based on indirect ELISA.

Hepatitis B surface antigen serology

Microscreen HBsAg ELISA test kits (Span Diagnostic Ltd.,) were used for detection of HBsAg. The test is based on solid phase microplate direct ELISA (Sandwich ELISA) technique.

Hepatitis c virus serology

SD HCV ELISA 3.0 (SD Bio-standard diagnostic Pvt., Ltd.,) kits were used which is indirect sandwich ELISA for the qualitative detection of antibodies against HCV. It contains a microplate, which is precoated with recombinant HCV antigens (Core, NS3, NS4, and NS5) on the well. The amount of conjugate bound and hence color, in the wells, is directly related to the concentration of antibody in the sample.

Syphilis serology

Syphilis was diagnosed using Accucare™ rapid plasma reagin (RPR) syphilis screening test (Lab-care Diagnostic Pvt., Ltd.,). The RPR syphilis screening test is macroscopic nontreponemal flocculation card test for detection and to quantify reagin, an antibody-like substrate present in serum or plasma and spinal fluid from syphilitic persons.

Quality control

Internal and external quality controls were carried out.

Statistical analysis

After data collection, data entry was done in Excel. Data analysis was done with the help of Statistical Package for Social Science version 15 (IBM SPSS Version 15). Qualitative data were analyzed with the help of frequency and percentage table. The association among various study parameters was assessed with the help of Chi-square test. P < 0.05 consider as statistically significant.

Results

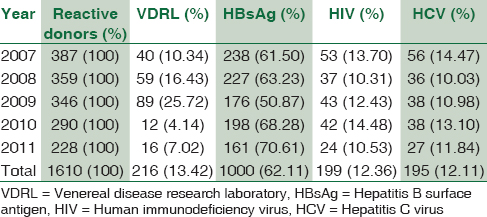

The study included a total of 76,653 healthy donors, out of which 70,363 (91.79%) were males and 6290 (8.21%) were females [Table 1]. Most of them 60,214 (78.55%) were voluntary donors and the remaining were family donors. Their ages ranged from 18 to 60 years. Out of 76,653 donors, 199 donors (0.26%) were HIV-positive, 1000 donors (1.30%) were HbsAg positive, and 195 donors (0.25%) were HCV positive while VDRL reactivity was seen in 216 donors (0.28%). The overall prevalence of HIV, HBsAg, HIV, and syphilis was 0.26% 1.30%, 0.25%, and 0.28% respectively which was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.001). There were 6 (0.007%) donors with multiple infection out of which 4 were found with HIV and HBsAg coinfection and two co-infected with HIV and syphilis. However, none of the donors displayed the presence of all three viral markers. No blood donor tested showed positivity for malarial parasite.

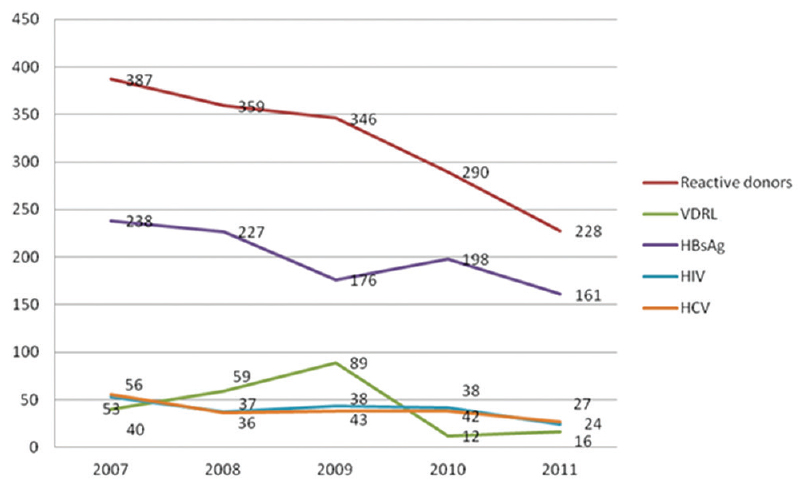

The trends in the seroprevalence of HIV, HBsAg, HCV, and syphilis over the 5-year period are shown [Figure 1 and Table 2]. The number of blood donors progressively increased from 2007 to 2011; however, the seropositivity was decreased over the years. In addition, after seeing the trend over 5 years, it was noted that >90% of the donors were men which is found to be statistically significant (P < 0.001).

- Trends in the seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis b surface antigen, hepatitis c virus and syphilis over the 5-year period

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV, and syphilis among healthy blood donors. Most of the donors in our study were males 70,363 (91.79%) aged between 18 and 60 years. This result is comparable with other studies of Buseri et al.,[1] Anjali et al.,[3] Pallavi et al.,[4] Tessema et al.,[5] and Matee et al.[7] Seropositivity rate was high among males in our study.

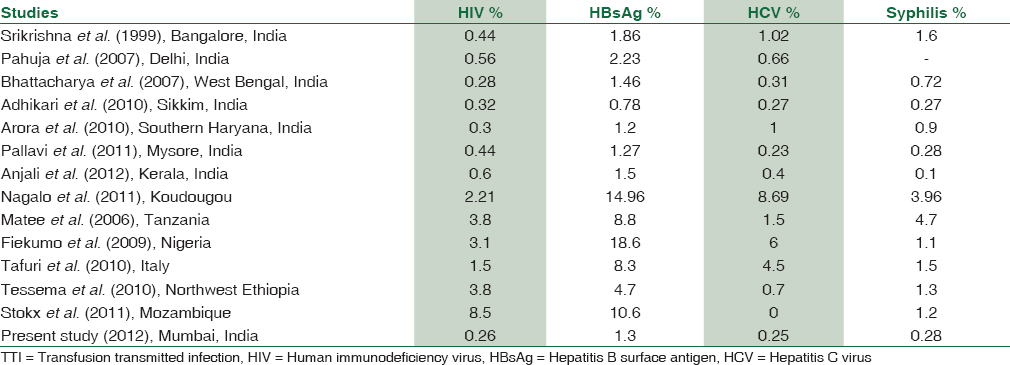

The donors were mainly voluntary donors. Voluntary donors are those donors who donate blood at regular intervals constituted 60,214 (78.55%) in our study. This is comparable to the study done by Matee et al.[7] The seroprevalence of the HIV, HBV, HCV, and syphilis were 0.26%, 1.30%, 0.25%, and 0.28%, respectively which is comparable with other studies such as Adhikari et al.,[8] Anjali et al.,[3] Pallavi et al.,[4] Pahuja et al.,[9] Arora et al.,[10] Bhattacharya et al.,[11] and Srikrishna et al.[12] as shown in Table 3. However, this seroprevalence rate is lower than studies done by Matee et al.,[7] Stokx et al.,[13] Tafuri et al.,[14] Tessema et al.,[5] Nagalo et al.,[2] Buseri et al.[1] as shown in Table 3. The reason for the quite lower prevalence of TTI compared to that in previous reports could be due to the reason that this study was carried in the academic institute where before donating blood awareness about TTI were given to donors.

It was also found that among 1610 (2.10%) seropositive donors, 6 (0.007%) donors had dual infections, commonly HIV and HBsAg coinfection followed by HIV and syphilis coinfection. These could be due to the fact that all these infections are sexually transmitted. However, none of the donors showed reactivity for all four infections (HIV, HBV, HCV, and syphilis).

HBV incidence is higher in our population. HBV positivity indicates a carrier state or an active infection. These seropositive donors may progress to develop chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and even progress to hepatocellular carcinomas.[1415]

Patients requiring blood transfusion are more prone to acquire HBV, HIV, HCV, and syphilis.[16] HBV is highly contagious and easily transmitted from one individual to another by transfusion during birth, by unprotected sex and by sharing needles. Syphilis can be spread by sexual contact, blood transfusion and by vertical transmission. Due to the nature of blood born virus, HCV is widely recognized as a major causative agent for posttransfusion non-A, non-B hepatitis. Other less common routes of transmission are sexual intercourse and mother to child transfer.[17] In case of HIV, transmission during window period is possible even if each unit is tested for HIV antibodies. The possibility of window period transmission would be minimized if blood is collected from low risk targeted general public.[18] However, blood safety remains an issue of major concern in transfusion medicine. However, HBV and HIV can also be transmitted from person to person contact, especially HBV which is transmittable from tears, urine, etc., Seroprevalence of HBsAg ranges from intermediate (2%–7%) to high (>8%) levels in India. High prevalence rate of 10% has been seen in Southern China, Korea, Melanesia, the Philippines, India, Indonesia, Japan, and Pakistan have intermediate rates of endemicity. However, these rates may be inaccurate and possible the tip of the iceberg as rates of occult HBV infection are not included in this.[19]

The course of HBV infection depends on many factors that can influence the immune system including age at infection and host genetic factors and genetic variability of viruses.[20] There are various HBV subtypes, subgenotypes, and escape mutants which cause public health concern through reinfection and occult infection. This is particularly true in Asia with its intermediate to high rates of chronic infection. These HBV isolates may escape detection and enter the blood supply. To lower the seroprevalence, there should be stringent donor selection criteria, blood donation by regular volunteer donors, effective donor education and counseling of seropositive donors. To make aware the general public about the highly infectious nature of these infections and its mode of transmission, special intervention programs should be planned.[21] Similarly, posttransfusion HBV infection rate is high due to the fact that HBV circulates at very low and undetectable level for screening assays. It is, therefore, necessary to find out the tests which detect the presence of Hepatitis B during the window period. Nucleic acid testing (NAT) assays are very useful in this situation which has considerably shortened the window period. However, the cost of this assay is high which makes it unaffordable for many centers.[22] There is 1% chance of transfusion-associated problems including TTI with each unit of blood.[4]

According to the WHO report, viral dose in HIV transmission through blood is so large that one HIV-positive transfusion leads to death on an average after 2 years in children and 3–5 years in adults.[4] HBsAg seroprevalence in India is high in spite of a safe and effective vaccine has been available. Sexually transmitted infections constitute a major public health problem and are widespread in developing countries. Syphilis has also acquired a new potential for morbidly and mortality through association with increased risk of HIV infection, thus making safe blood more difficult to get. The residual transmission risk of HBV infection through a transfusion is higher due to a long window period between initial HBV infection and the detection of HBsAg during which the virus is transmissible.[23]

Selection of donors with low TTI risk and effective laboratory screening is the very important part in blood bank processing which has reduced the risk of transmission to very low levels.[24]

Limitation of our study is that all TTI such as leishmaniasis and toxoplasmosis have not been covered.

Conclusion

The study reflects the seroprevalence of the general population in our area which may be helpful in planning public health interventional strategies. In our retrospective study of 76,653 donors, we estimated overall prevalence of HIV, HBsAg, HIV, and syphilis were 0.26% 1.30%, 0.25%, and 0.28%, respectively. Methods to ensure a safe blood supply should be encouraged. Screening with a better selection of donors and use of sensitive screening tests including NAT assay will definitely reduce the risk of TTI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sero-epidemiology of transfusion-transmissible infectious diseases among blood donors in Osogbo, South-West Nigeria. Blood Transfus. 2009;7:293-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses and syphilis among blood donors in Koudougou (Burkina Faso) in 2009. Blood Transfus. 2011;9:419-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transfusion-transmissible infections among voluntary blood donors at Government Medical College Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2012;6:55-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence and trends in transfusion transmitted infections among blood donors in a University Hospital blood bank: A 5 year study. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2011;27:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis infections among blood donors at Gondar University Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: Declining trends over a period of five years. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis C virus in apparently healthy Port Harcourt blood donors and association with blood groups and other risk indicators. Blood Transfus. 2008;6:150-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses and syphilis infections among blood donors at the Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infectious disease markers in blood donors at Central Referral Hospital, Gangtok, Sikkim. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2010;4:41-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and trends of markers of hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus and human immunodeficiency virus in Delhi blood donors: A hospital based study. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007;60:389-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis in blood donors in Southern Haryana. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:308-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Significant increase in HBV, HCV, HIV and syphilis infections among blood donors in West Bengal, Eastern India 2004-2005: Exploratory screening reveals high frequency of occult HBV infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3730-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of transfusion-transmissible infections and evaluation of the pre-donation screening performance at the Provincial Hospital of Tete, Mozambique. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:141.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hepatitis B, C, HIV and syphilis markers among refugees in Bari, Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:213.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of antibody to hepatitis B core antigen in multitransfused hemodialysis patients. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2009;3:14-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of HBV and HCV in blood donors: A study from regional blood transfusion services of Nepal. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2010;4:91-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus in Nepalese blood donors: A study from three regional blood transfusion services. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2008;2:66-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of new cases of HCV infection in thalassaemia patients for source of infection. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;5:132-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of hepatitis B virus genotypes among healthy blood donors in Eastern part of North India. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;5:144-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis B core antibody testing in Indian blood donors: A double-edged sword! Asian. J Transfus Sci. 2012;6:10-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among Albanian blood donors, 1999-2009. Virol J. 2011;8:96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and trends of transfusion transmitted infections in a regional blood transfusion centre. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;5:177-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis in voluntary blood donors. Indian J Med Sci. 2004;58:255-7.

- [Google Scholar]