Translate this page into:

Occupational Sharp Injury and Splash Exposure among Healthcare Workers in a Tertiary Hospital

Address for correspondence: Ritin Mohindra, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Research, Chandigarh, India (e-mail: ritin.mohindra@gmail.com).

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background

Occupational hazards like sharp injury and splash exposure (SISE) are frequently encountered in health-care settings. The adoption of standard precautions by healthcare workers (HCWs) has led to significant reduction in the incidence of such injuries, still SISE continues to pose a serious threat to certain groups of HCWs.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study which examined the available records of all patients from January 2015 to August 2019 who self-reported to our emergency department with history of sharp injury and/or splash exposure. Details of the patients, mechanism of injury, the circumstances leading to the injury, status of the source (hepatitis B surface antigen, human immunodeficiency virus, and hepatitis C virus antibody status), and the postexposure prophylaxis given were recorded and analyzed. Data were represented in frequency and percentages.

Results

During the defined period, a total of 834 HCWs reported with SISE, out of which 44.6% were doctors. Majority of the patients have SISE while performing medical procedures on patients (49.5%), while 19.2% were exposed during segregation of waste. The frequency of needle stick injury during cannulation, sampling, and recapping of needle were higher in emergency department than in wards. More than 80% of HCWs received hepatitis B vaccine and immunoglobulin postexposure.

Conclusion

There is need for periodical briefings on practices of sharp handling as well as re-emphasizing the use of personal protective equipment while performing procedures.

Keywords

needle stick injury

healthcare workers

occupational hazards

postexposure prophylaxis

Introduction

Occupational hazards like sharp injury and splash exposure (SISE) are frequently encountered in healthcare settings. The term “needle stick injury” (NSI) is a broad term that encompasses injuries caused by needles and/or other sharp objects (e.g., glass vials, surgical blades, and forceps), which accidentally puncture the skin. The adoption of standard precautions by healthcare workers (HCWs) has led to significant reduction in the incidence of such injuries. However, SISE still continues to pose a serious threat to certain groups of HCWs, especially surgeons, emergency room workers, laboratory room professionals, and nurses. This is largely attributable to the failure to fully adhere to the established protocols for standard precautions.[1]

SISE is associated with transmission of blood-borne pathogens, of which the major concerns are hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[2,3] The reported risks of contracting these infections after sustaining pathogen-positive NSIs range from 0.1 to 0.3% for HIV, 6.0 to 30.0% for HBV, and 0 to 10.0% for HCV.[4] In addition to causing potential threats due to these infections, SISEs also have direct costs which are spent for the laboratory testing for these pathogens among exposed individuals.[5] Other costs include costs related to postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for the HCWs, as well as the economic loss imposed on hospitals because of the absence of HCWs from work.[6]

Pre-exposure vaccination as a mode of protection from such exposures is available only for HBV.[7] The uniform adoption of standard precautions and safe practices by the HCWs is the only definitive way to prevent SISE. This study was undertaken to assess the profile of HCWs who had a SISE, and to see the practices adopted following a SISE in a tertiary care teaching hospital in India.

Materials and Materials

This retrospective study examined the available records of all patients from January 2015 to August 2019 who self-reported to our emergency department with history of sharp injury and/or splash exposure. Our emergency department is the designated nodal point for HCWs for reporting any incident of SISE and to receive the PEP. A SISE register is maintained where the details of the HCW reporting with SISE is recorded, which includes details of the patients, mechanism of injury, the circumstances leading to the injury, status of the source (HBsAg, HIV, and HCV antibody status), and the PEP given. Any missing data with regards to vaccination was assumed as not given. HCWs reporting with SISE to the emergency immediately receive hepatitis B vaccine; hepatitis B immunoglobulin depending on their anti-HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen) titers; tetanus toxoid if they have not received the same in the past 5 years or they are not aware of their vaccination status; and receive first dose of antiretroviral therapy (ART) as per the National AIDS Control (NACO) guidelines.[8] The blood samples for viral markers (HBV, HIV, and HCV) of the HCW and the source patient (if known) are sent to the virology laboratory for testing, and subsequently, patient is referred for outpatient follow-up to the ART clinic. A total of 842 patients presented to us from January 2015 to August 2019, out of them 8 were excluded as they were not HCWs.

Data were extracted from the records register and entered in the excel sheet which was password protected, double encrypted, and the name of the patient was de-identified to maintain the confidentiality as well as security of the data. Data were represented in frequency and percentages. Chi-square test was applied to compare between groups. The p-value < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant. Ethical clearance was taken by institutional review board (IEC/828/10/2019), and analysis was done in SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States).

Results

During the period of 3 years and 8 months included in the study, a total of 834 HCWs reported with SISE out of which 44.6% were doctors. Among the doctors, junior residents were the most frequently affected (37.1%). Highest number of SISE was reported from the wards (41.1%) followed by emergency (40.3%). NSI was the most common mode of injury (►Table 1).

| Frequency (n) | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 522 | 62.6 |

| Female | 312 | 37.4 | |

| Profession | Doctors | 376 | 44.6 |

| Consultant | 7 | 0.8 | |

| Senior residents | 52 | 6.2 | |

| Junior residents | 309 | 37.1 | |

| Interns | 7 | 0.8 | |

| Students | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Nurses | 268 | 31.7 | |

| Nursing officers | 243 | 29.1 | |

| Nursing students | 25 | 3.0 | |

| Hospital attendants | 165 | 19.8 | |

| Technicians | 25 | 3.0 | |

| Place of Work | Emergency | 336 | 40.3 |

| Ward | 343 | 41.1 | |

| Operation Theater | 69 | 8.3 | |

| ICU | 43 | 5.1 | |

| Laboratory | 27 | 3.2 | |

| Out patient | 11 | 1.3 | |

| Others | 5 | 0.5 | |

| Mode | Needle prick | 793 | 95.1 |

| Surgical blade | 14 | 1.7 | |

| Body fluid splash | 27 | 3.2 | |

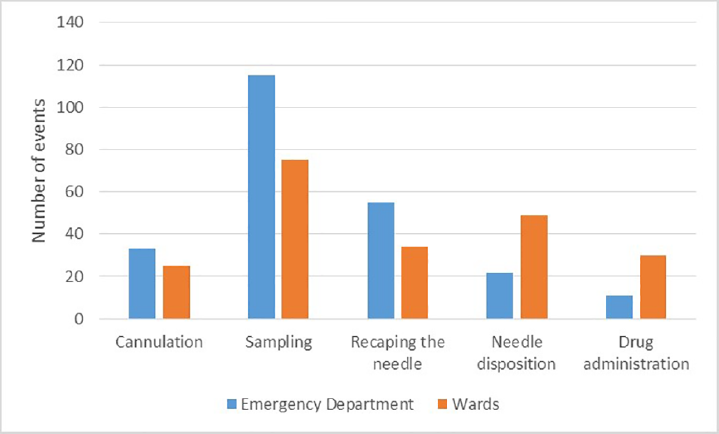

There was more incidence of NSI while sampling (115) and recapping (55) in the emergency, whereas in wards more incidents happened while drug administration (49) and disposing the needle (30) (►Table 2). The frequency of NSI during cannulation, sampling, and recapping of needle was higher in emergency department than in wards (p = 0.272, p < 0.001, and p = 0.012, respectively), whereas the frequency of NSI during needle disposition and drug administration was higher in wards than in emergency department (p = 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively; ►Fig. 1).

- Difference in sharp injury and splash exposure between emergency department and wards.

| Mechanism of injury | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| During procedures | 413 | 49.5 |

| Sampling | 209 | 25.1 |

| Central line insertion | 70 | 8.3 |

| Surgery | 69 | 8.1 |

| Cannulations | 64 | 7.5 |

| Delivery | 1 | 0.1 |

| During segregation of waste | 162 | 19.4 |

| While recapping needle | 100 | 12.0 |

| While disposing needle | 90 | 10.8 |

| While drug administration | 45 | 5.4 |

| While taking blood sugar | 24 | 2.9 |

Hepatitis B was the most common infection prevalent in known sources (7.7%). Next was HIV (2.6%), followed by hepatitis C (1%), which was positive in eight source patients, and in rest the source status was unknown.

More than 80% of HCWs received hepatitis B vaccine and immunoglobulin postexposure. Three HCWs refused treatment (►Table 3).

| PEP received | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B vaccine | 725 | 86.9 |

| Hepatitis B immunoglobulin | 687 | 82.4 |

| Antiretroviral therapy | 308 | 36.9 |

| Tetanus toxoid | 117 | 14.0 |

| None | 3 | 0.3 |

Abbreviation: PEP, postexposure prophylaxis.

However, 602 HCWs received both hepatitis B vaccine and immunoglobulin after the exposure, while 123 HCWs decided to take only the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine as they sent sample of the source patients and themselves for anti-HbsAg titers.

Discussion

Sharp injury and splash exposure are occupational hazards that expose the HCWs to blood-borne infections, which affect them physically and psychologically. Our study revealed that doctors were most commonly affected population among the HCWs. The findings were similar to previous studies done in different tertiary care hospitals, where the resident doctors are the major working force in the hospital.[9,10] Studies have shown that stressful psychosocial conditions and improper knowledge about safe disposal lead to increased incidence of NSI.[11-13] This emphasizes the need of a training workshop in using personal protective equipment and safe practices of sharp handling for resident doctors.[14]

Though the highest reported incidence was from the wards, almost similar number of cases were reported from emergency department (ED). There could be several reasons for this: first, our emergency department has the largest strength of HCWs; second, there are lots of high acuity patients and overcrowding in the ED; and finally, since ED is the nodal point for reporting SISE and receive PEP, residents posted there tend to report more.

Among sharp injuries, the most common mechanism was needle prick by hypodermic needles and suture needles, which was similar to previously reported literature.[15,16] Almost half of them occurred while performing various procedure like sampling, cannulations, central line placement, and surgical procedures. About 19.4% of the HCWs received NSI while segregating the waste. This points to the lack of training in proper sharp disposal techniques leading to untoward events, which otherwise are completely avoidable. Use of puncture proof bags and rubber gloves while collecting and disposing wastes should be promoted.

On comparing different mechanism of injury in wards and emergency, we found that in emergency more events of NSI happened while sampling and recapping the needle. This could be because of the urgency involved in managing patients in ED that people tend to forget taking basic precautions. The training sessions organized for HCWs should emphasize on these mechanisms separately for emergency and ward.

Twenty-seven patients were exposed to body fluid splash while performing procedures. Prevention of splash exposures via the use of protective goggles and face shields while performing procedures should be reinforced by regular training of HCWs. Mandatory infection control briefings, with emphasis on use of personal protective equipment and proper waste disposal and, use of safety control devices in required to reduce such incidents.[17,18]

After an SISE, the HCW should clean the wound; identify the patient source and their HIV, HBV, and HCV status; and contact the designated doctor responsible for guiding the further line of management. The treating physician then carefully weighs the source patient's disease status, exposure type, and seroconversion risk and then educate the HCW about the available options for PEP.[19] Although in our study, the status of the source was unknown, yet more the 80% of the HCWs were given hepatitis B immunoglobulin and hepatitis B vaccine. This was because most of the HCWs were not aware of their anti-HBsAg titers at the time of their exposure and were given PEP to avoid delay as risk of transmission is as high as 30%. CDC advocates concurrent use of hepatitis B immunoglobulin and vaccine for PEP.[20] This highlights the need of routine antibody titer testing in all HCWs when they join their service, which will reduce the extra cost of giving immunoglobulin to every HCW postexposure. In contrast, first dose of ART postexposure was only taken by 37% of the HCWs. This was mainly because of two reasons: first, the NACO does not advocate routine PEP if source status is unknown[8] as there is low rate of transmission by NSI in cases of HIV; and second, due to the side effects associated with taking ART. However, the samples of the source patient are immediately sent for testing, and the HCW is referred to the ART clinic to decide further course of action.

Spread of tetanus from SISE is highly unlikely unless the source is contaminated. However, tetanus vaccination is recommended in cases of NSI encountered while segregation of waste and in those who have not received tetanus toxoid booster within the past 5 years. In our study, a total of 117 HCWs received TT vaccine, of which 46 were exposed while segregating waste. The perception that NSI carry low risk of transmission of infection can lead to under reporting.[21] Sensitizing the HCWs about the various infections they are susceptible to while handling sharps can help in better compliance.

In conclusion, our study found that junior residents are frequently affected by SISE. There is a need for periodical briefings on practices of sharp handling as well as re-emphasizing the use of personal protective equipment, including glasses, while performing procedures.

Authors’ Contributions

R.M., R.Mo., and P.A. were involved in the conception of idea. R.M., A.S., and A.R. extracted data. R.M. and A.S. assisted in data analysis. R.M. and R.B. supported in writing the first draft of the manuscript. R.Mo., and P.A. performed critical revision of the manuscript. All authors take full responsibility of the originality of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

- Needlestick. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing 2019 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493147/. Accessed July 20, 2019

- [Google Scholar]

- Needle stick injury and HIV risk among health care workers in North India. Indian J Med Sci. 2011;65(09):371-378.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occurrence of needlestick and injuries among health-care workers of a tertiary care teaching hospital in North India. J Lab Physicians. 2017;9(01):20-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National incidence of percutaneous injury in Taiwan healthcare workers. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(02):172-179.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- et al Occupational exposure to needlestick injuries and hepatitis B vaccination coverage among health care workers in Egypt. Am J Infect Control. 2003;31(08):469-474.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle stick injuries & the health care worker–the time to act is now. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:384-386.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in healthcare workers of a tertiary care centre in india and their vaccination status. J Vaccines Vaccin. 2011;02(2)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Available at: http://naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/NACO%20-%20National%20Technical%20Guidelines%20on%20ART_October%202018%20%281%29.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2019

- Needle-stick injury among health care workers and its response in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2016;34(02):258-259.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle stick injuries in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27(01):44-47.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between psychosocial working conditions, stress perception, and needle-stick injury among healthcare workers in Shanghai. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(01):874.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude, and practice of needle stick and sharps injuries among dental professionals of Bangalore, India. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5(05):406-412.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job stress and needlestick injuries: which targets for organizational interventions? Occup Med (Lond). 2016;66(08):678-680.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- et al Needlestick injury prevention training among health care workers in the Caribbean. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2018;42:e93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of needlestick and sharp injuries among health care workers based on records from 252 hospitals for the period 2010-2014, Poland. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(01):634.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional observational study to assess the awareness regarding needle prick injuries among health care providers of a tertiary care teaching hospital in Madhya Pradesh, India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6(06):2440-2443.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- et al Incidence and analysis of sharps injuries and splash exposures in a tertiary hospital in Southeast Asia: a ten-year review. Singapore Med J. 2019;60(12):631-636.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Published September 27, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/eye/eye-infectious.html. Accessed October 5, 2019

- [Google Scholar]

- Available at: https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/124195/what-should-i-do-if-i-get-needlestick. Accessed October 5, 2019

- Guidance for Evaluating Health-Care Personnel for Hepatitis B Virus Protection and for Administering Postexposure Management. Accessed October 6, 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6210a1.html. Accessed October 5, 2019

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour towards needlestick injuries among junior doctors. Occup Med (Lond). 2019;69(06):436-440.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]