Translate this page into:

Monkey B virus- An emerging threat?

*Corresponding author: Gursimran Kaur Mohi, Department of Virology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. gkmohi@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Roy M, Kaur S, Mohi GK. Monkey B virus- An emerging threat? J Lab Physicians. doi: 10.25259/JLP_321_2024

Abstract

A death from Monkey B virus (Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1) infection was recently reported in China, reminding us to be on the lookout for the risk of transmission and infection with Monkey B virus. Monkey B virus is found in macaques of the genus Macaca, which are widely used in biomedical research. Although B virus infection in macaques is usually asymptomatic or mild, it can be fatal in humans, causing encephalomyelitis. Without prompt treatment, the mortality rate from Monkey B virus infection can reach more than 70%. Although the risk of human-to-human transmission is low, the virus’s widespread prevalence among monkeys, high mortality among infected individuals, and severe neurological sequelae in survivors make this virus an important zoonotic pathogen that threatens humans. Training programs for at-risk personnel and prompt treatment after Monkey B virus exposure can reduce infection rates and mortality. Following a rapid diagnosis of Monkey B virus disease, the early initiation of antiviral therapy prevents severe disease or death. The identification of risk factors is critical in controlling the spread of the Monkey B virus in the vulnerable population.

Keywords

Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1

Monkey B virus

Zoonotic virus

INTRODUCTION

The first case of the Monkey B virus or Herpes B virus was discovered by Gay and Holden in 1932 in Dr. William Brebner, a 29-year-old working in polio research who was bitten by a seemingly healthy Macaques rhesus monkey. He started showing symptoms of ascending myelitis on day 13 and passed away on day 17. Although it did not affect monkeys, the infected tissue from the case led to comparable lesions in rabbits. After being discovered to have characteristics of the herpes virus, this virus was given the name B virus in honor of the patient Dr. W.B.[1]

In China, the first case of the Monkey B virus was identified in 2021 in Beijing, in a 53-year-old male veterinarian specializing in nonhuman primate breeding and experimental research. He performed the dissections of two deceased monkeys on March 4 and March 6, respectively, after which he experienced nausea and vomiting, followed a month later by neurological problems, and ultimately passed away on May 27, 2021, despite visiting multiple hospitals. This example suggested that the Monkey B virus could pose a zoonotic concern to veterinary researchers and animal caretakers who work with macaques, as they are important nonhuman primate models for biomedical research.[2]

ETIOLOGY

Although Monkey B virus has been referred to by several names throughout the years, including Herpes simiae, B virus, and Herpes B, the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses has given it the official name Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1.[3]

Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1 is a member of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae of the genus Simplexvirus. In its native hosts, i.e., Asian monkeys of the genus Macaca, it typically causes minor localized or asymptomatic infections only. In the natural host, Monkey B virus causes infections that are similar to herpes simplex virus (HSV) in humans. However, in foreign hosts, including humans and even other monkey species except macaques, it can cause potentially fatal illnesses, including encephalitis and encephalomyelitis.[3]

The puzzling aspect is the lack of Monkey B virus reported cases in Asia, even though Monkey B virus positive macaques have close interactions through bites or scratches, particularly in thousands of temples from east of Afghanistan to Japan. Humans are exposed to these Macaques, which include Rhesus, Long-tailed, and Pig-tailed monkeys, during food handouts, particularly among international tourists. Hence, the question of whether Monkey B virus is zoonotic in Asia remains unanswered. Or it could be a lack of diagnosis that prevents the Monkey B virus from being detected.[4] In this article, we review this neglected virus causing neurovirulence.

TRANSMISSION

Humans contract the Monkey B virus infection primarily through direct contact with infected tissue or monkeys’ contaminated saliva. There are many ways that the Monkey B virus can spread, including direct inoculation with monkey tissue or fluid through bites, scratches, or cage scratches; direct contamination of a wound with monkey saliva; needle-stick injuries; and airborne infection.[1,2,5-16] In addition, a case of person-to-person spread has also been reported.[13] In humans, the time it takes for the disease to develop symptoms after exposure can range from <2 days to 10 years. A potential instance of Monkey B virus latency has also been reported in humans.[12]

PATHOGENESIS

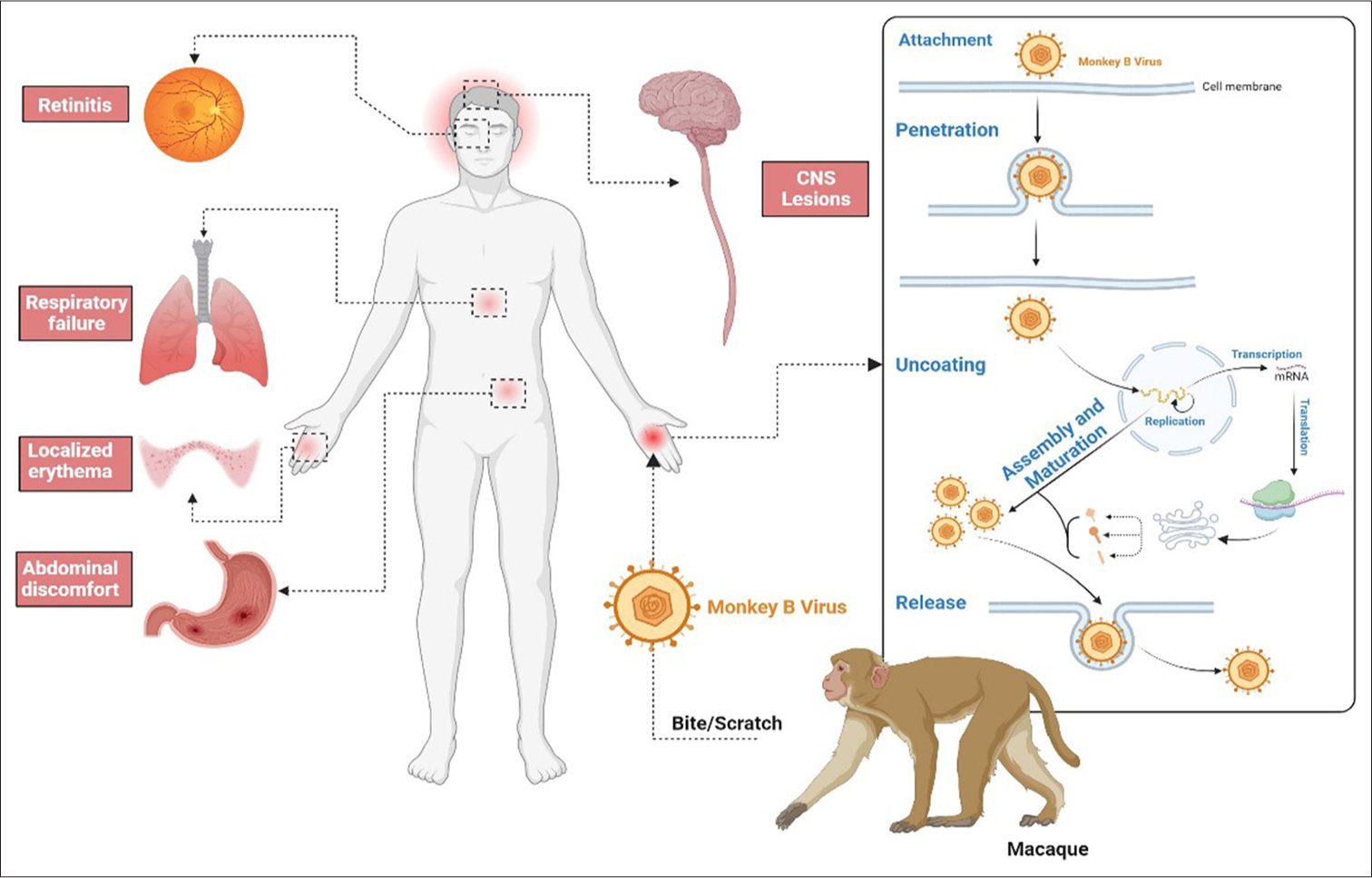

In terms of pathophysiology, antigenicity, structure, as well as processes of infection and reproduction, Monkey B virus is similar to herpes simplex virus. The virus infects a target host cell by fusing its viral envelope with the cell’s plasma membrane after binding to the surface receptors on the target host cell. Once the naked capsid has passed through nuclear pores, the viral DNA is subsequently released into the nucleus. The viral progeny are discharged from the host cell after replication which takes place in the nucleus, continuing the infection cycle. Monkey B virus titers stabilize 24–36 h after infection, although detection can occur as early as 6 h after infection.[17] Occasionally, syncytia or polykaryocytes are discovered after the infection. In Monkey B-virus-infected epithelial cells during the replication cycle, Cowdry type A intranuclear inclusion bodies, which are virus induced and are a typical herpes virus cytopathic effect of syncytia formation, are discovered; this occurs concurrently with host-cell shutdown of macromolecular synthesis, margination of chromatin, cellular swelling, and, ultimately lysis[18,19] [Figure 1].

- Pathogenesis and clinical features of Monkey B virus.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Monkey

Rhesus and cynomolgus or long-tailed monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) have been the subjects of most reports of natural Monkey B virus infections in macaques, though isolations from bonnet (Macaca radiata), Japanese (Macaca fuscata), Taiwan (Macaca cyclopis), and stump-tailed (Macaca arctoides) macaques have also been noted. Three patas monkeys (Erythrocebus patas) and one black-and-white colobus monkey (Colobus abyssinicus) that were housed close to a colony of rhesus monkeys in a zoo in the United States were also discovered to have possible Monkey B virus infections. As previously reported, common marmosets and capuchin monkeys, two species of New World monkeys, were experimentally infected with the virus and developed deadly neurological illnesses (Callithrix jacchus).[20] Although no publications have been found in African Old-World monkeys, the closely related alpha herpesvirus SA8 is present in baboons (Papio species) naturally and has a pathogenesis that appears to be comparable to that of Monkey B virus.[18] There are no reports of Monkey B virus in African Old-World monkeys, even though primates are the natural hosts and can contract a disease that resembles herpes simplex in humans. The primary infection is typically gingivostomatitis, which is characterized by one or more vesicles that burst in 3–4 days and leave ulcers.[19] In addition, the conjunctiva and skin may develop lesions.[18,21,22] Primary infection typically has minor signs and symptoms, and the illness goes undiagnosed most of the time. Bacteria and fungi can occasionally cause a secondary infection of the sores. Systemic signs, such as widespread viral infection, cerebral infarction, interstitial hemorrhagic pneumonia, and localized hepatitis, are more common in macaques than in rhesus monkeys.[18] Monkey can become latent in the sensory ganglia and cause repeated infections in some animals, just like the herpes virus does in humans. In asymptomatic monkeys, the virus occasionally sheds into the saliva and genital secretions.[23,24] Intranuclear inclusion bodies, ballooning of cells, necrosis of epithelial cells, and mild inflammation that varies with the severity of secondary infection are all signs of Monkey B virus infection, which shares histological characteristics with Herpes Simplex virus infection in humans.[22]

Humans

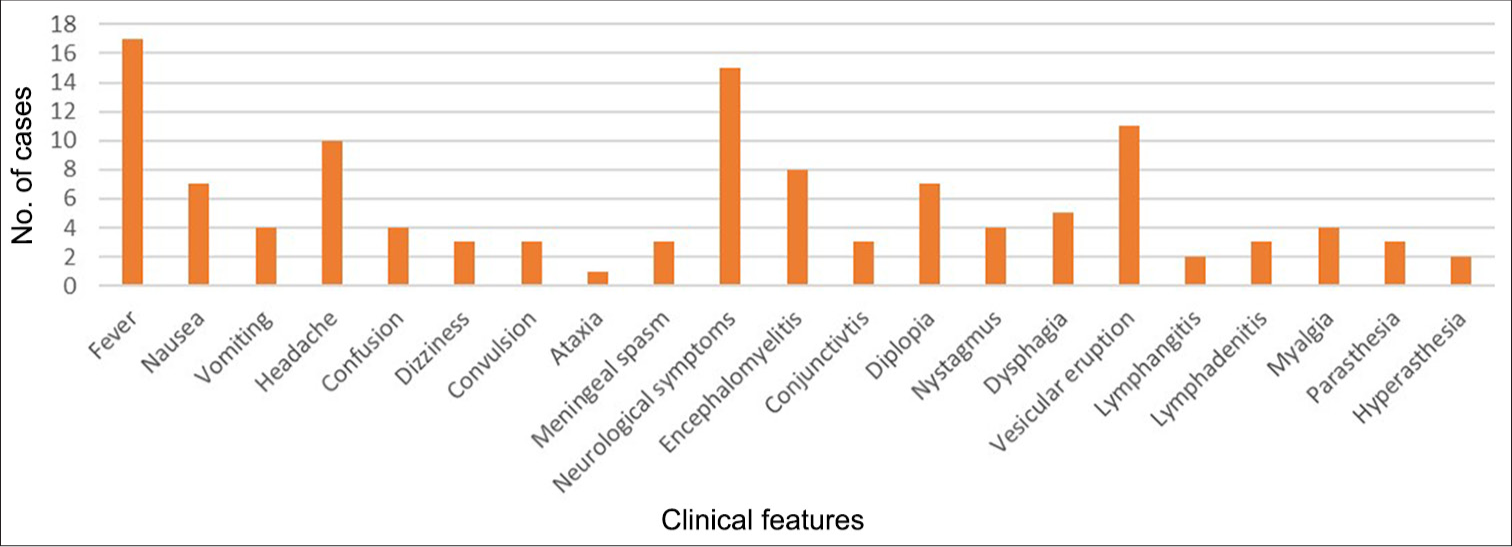

They primarily result in mortality in humans. For the most part, constitutional symptoms such as fever, flu-like aches and pains, particularly muscular pain, exhaustion, and headache begin first. Hiccups, vomiting, nausea, lymphadenitis, and lymphangitis are other symptoms. Most of the time, neurologic symptoms such as ataxia, diplopia, agitation, and ascending flaccid paralysis appear. Less often seen symptoms include urinary retention, seizures, and confusion. Coma and death may result from encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, and respiratory failure.[1,2,5-16] The majority of symptoms are depicted in Figure 2.

- Clinical features documented in Monkey B Virus positive patients.

REVIEW OF CASES TILL NOW

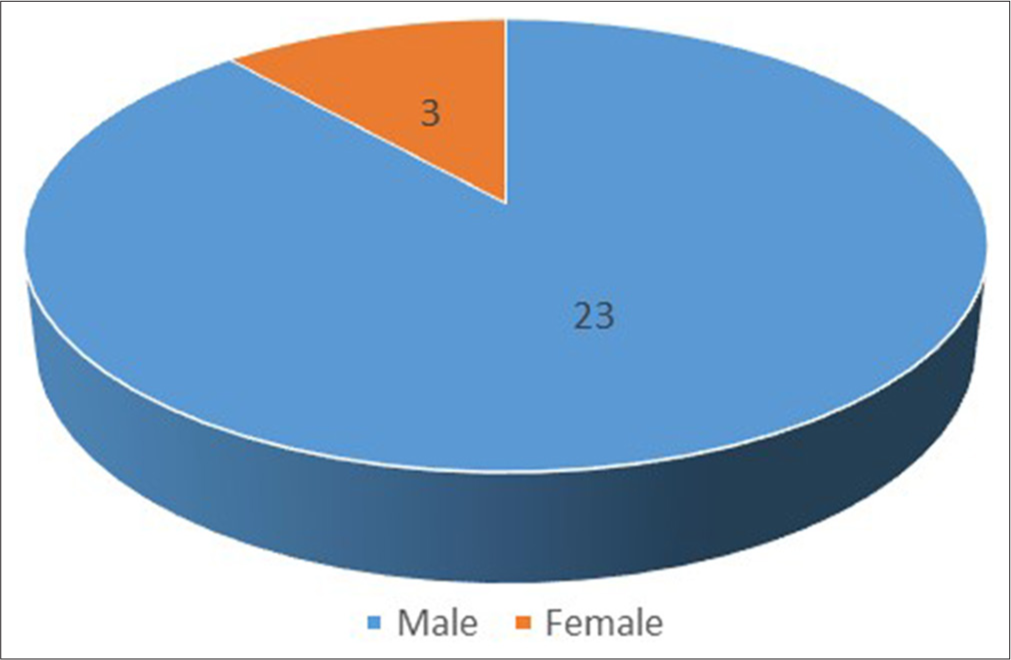

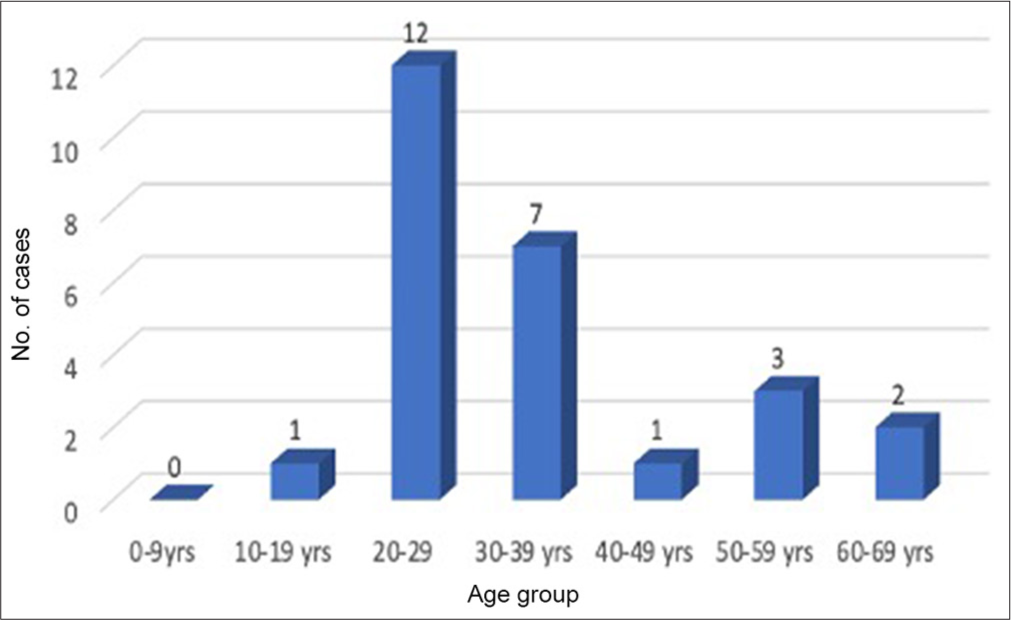

There have been around 50 recorded cases thus far, of which 26 have documentation. They are primarily male and between the ages of 20 and 29 [Figures 3 and 4]. The bulk of the patients are veterinarians, lab technicians, or animal handlers, which is a significant discovery. Only one case has been documented to date in which the patient had indirect interaction with humans rather than direct contact with primates.[12] This information indicates that the Monkey B virus is a zoonotic infection, putting the safety of lab workers and animal handlers in jeopardy. Only 7 persons out of all the known cases survived [Table 1]. The case fatality rate in humans is more than 70%.[2]

- Gender distribution of documented patients affected by Monkey B virus.

- Age distribution of documented patients affected by Monkey B virus.

| Year of incident/report | State/country | Source of infection | Occupation | Age | Gender | Incubation period | Survival and cause of death (if mentioned) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | New York, USA | Monkey bite | Physician | 29 | Male | 3 days | 17 days. Respiratory faiulure.[2] |

| 1949 | Philadelphia, USA | Saliva to wound | Physician | 25 | Male | Unknown | Few days[5] |

| 1956 | Philadelphia, USA | Monkey bite and scratch | Animal attendant | 21 | Male | 1 month | 2 months[6] |

| 1956 | Philadelphia, USA | Monkey scratch | Animal attendant | 29 | Male | 2 days | Recovered[5] |

| 1957 | Ottawa, Canada | Unknown, Possible aerosols | Engaged in poliomyelitis vaccine preparation and was mainly occupied with the inoculation and autopsies of Rhesus monkeys. | 31 | Male | Unknown | 8 days.[7] |

| 1957 | Philadelphia, USA | Tissue culture bottle cut | Technician handling monkey renal cells | 21 | Male | 1month approx. | 15 days.[6] |

| 1957 | London, England | Monkey bite and scratch | Animal attendant | 31 | Male | 13 days | Recovered.[8] |

| 1957 | Philadelphia, USA | Cleaned monkey skull | Chemist | 30 | Male | 7 days | 3 days.[5] |

| 1957 | Philadelphia, USA | Monkey bite | Animal attendant | 19 | Male | 5 days | 26 days.[5] |

| 1958 | USA | Unknown | Animal attendant | 34 | Male | Unknown | 3 days[9] |

| 1958 | Philadelphia, USA | Needle stick injury | Animal attendant | 29 | Male | 5 days | 2 weeks approx.[5] |

| 1958 | Philadelphia, USA | Needle stick injury and monkey bite | Animal attendant | 40 | Male | Unknown | 5 weeks approx.[5] |

| 1959 | New York, USA | Monkey scratch | Worked with rhesus monkey | 24 | Male | 5 days | 3 months approx.[10] |

| 1963 | USA | Unknown | Worked with rhesus and African Green Monkey | 51 | Male | Unknown | 3 years.[11] |

| 1970 | California, USA | Possible reactivation | Virologist | 61 | Male | Unknown | Recovered.[12] |

| 1970 | USA | Unknown | Virologist | 62 | Male | Unknown | 5 days.[11] |

| 1987 | Florida, USA | Monkey bite | Research technician | 31 | Male | 5 days | 6 months. Cardiac arrest.[13] |

| 1987 | Florida, USA | Monkey bite | Biological technician | 37 | Male | 5days | 48 days.[13] |

| 1987 | Florida, USA | Cage scratch | Laboratory supervisor | 53 | Male | 3 days | Recovered.[13] |

| 1987 | Florida, USA | Human to human exposure | Wife of Monkey B virus positive patient | 29 | Female | Unknown | Recovered.[13] |

| 1989 | Texas, USA | Needle stick injury | Veterinary technician | 26 | Female | No symptoms | Survived[14] |

| 1989 | Michigan, USA | Monkey bite | Animal attendant | 22 | Male | 1 month approx. | 8 days.[16] |

| 1989 | Michigan, USA | Monkey bite and scratch | Animal attendant | 20 | Male | 15 days | Recovered.[16] |

| 1989 | Michigan, USA | Monkey bite and scratch | Animal attendant | 32 | Male | Unknown | Recovered.[16] |

| 1997 | USA | Ocular splash | Not mentioned | 22 | Female | 9 days | 42 days. Refractory respiratory failure.[15] |

| 2021 | China | Dissected monkey | Veterinary surgeon | 53 | Male | 1 month | 83 days.[1] |

LAB DIAGNOSIS

To combat the Monkey B virus mortality, both rapid diagnosis and high clinical suspicion are required. Initially, cell line culture, in Vero, LLC-MK2, was the mainstay of diagnosis.[24] Since it is a member of the risk group 4 pathogen, it must be studied in a BSL-3/4 facility, which makes in-depth research on this virus challenging.[25] For rapid and accurate virologic diagnosis of Monkey B virus infection, both in clinical diagnosis and for research reasons, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and restriction endonuclease analysis have been used alone. It has proven very challenging to detect the infection in asymptomatic patients since the specificity of the two diagnostic approaches depends on the presence of significant titers of actively infected viruses in the test sample.[13,20,24,26,27] Because HSV and monkey B antibodies react with one another, serological identification of antibodies is challenging. Serology uses ELISA and cellular enzyme assays as diagnostic tools. The most often found antigens are gB, gC, and gD, which have sensitivities of 100%, 97.30%, and 88%, respectively.[28,29] Nucleic acid detection using RT PCR, which detects the 5’ region of the gG gene, is one of the most recent diagnostic modalities. In the Point of Care test (POCT), LAMP is a promising diagnostic tool that can identify as low as 27.8 copies per reaction.[30,31]

PREVENTION

In settings where macaque monkeys are present, the Monkey B virus is a risk. The main bodily fluids linked to a risk of transmission are mucosal secretions, including saliva, vaginal secretions, and conjunctival secretions. Zoonoses have been documented as the result of bite, scratch, or splash accidents. Monkey B virus cases have also been documented following exposure to tissue from the central nervous system and to monkey cell cultures. However, the risks related to this danger can be easily decreased by using barrier precautions and by quickly and thoroughly cleaning up after a potential site contamination. When any macaque species is used for work, safety precautions must be taken.[32] In cases of skin exposure with loss of skin integrity, mucosal exposure, needlestick injury, deep puncture bite, and laceration injury following exposure to objects that are contaminated with either monkey oral fluid, genital lesions, or nervous system tissue known to contain Monkey B virus, Post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is advised. In cases of intact skin exposure or contact with nonmacaque species of nonhuman primates, no prophylaxis is advised. Cleaning the exposed area is part of the postexposure prophylaxis, which is to be followed by a medical professional’s evaluation. Even though there are not many reports of human-to-human transmission, anyone who may be affected should be warned to avoid touching others for the duration of the incubation period and even beyond. Acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are among the antivirals used in PEP, although none of them is food and drug administration (FDA)-recommended for Monkey B virus PEP.[33]

TREATMENT

Intravenous antiviral therapy must be started in the presence of any Monkey B virus illness signs or symptoms or upon laboratory confirmation of Monkey B virus infection. Given the unpredictable nature of rapid and life-threatening brain stem involvement, some specialists advise IV acyclovir in cases of disease without symptoms, while others advise IV ganciclovir.[33] If there are clear signs of CNS involvement, IV ganciclovir is advised. Early therapy initiation has been shown to increase patient survival in several circumstances. Standard safety precautions must be taken during the therapy.[33] There is disagreement on when to stop treatment, where one group of doctors advises that IV therapy must be continued until symptoms go away and ≥2 sets of cultures produce negative findings after being admitted for 10– 14 days, others contend that oral antivirals should be used instead.[33]

CONCLUSIONS

Monkey B virus is a rare but highly lethal zoonotic pathogen. Though it has relatively low prevalence in humans, its high mortality and morbidity potential demands vigilance. The relatively sparse documentation of human cases in Asia, where human-monkey interactions are quite frequent, highlights a significant gap in surveillance and diagnosis. Early recognition, rapid laboratory diagnosis, and timely therapeutic interventions are critical for improving survival outcomes. Increased awareness among at-risk populations and the development of sensitive diagnostic tools are essential to mitigate the risk posed by this neglected but potentially fatal virus.

Authors’ contribution:

MR: Literature search, data acquisition, data analysis, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation; SK: Manuscript preparation, manuscript editing; GKM: Concept, design, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review.

Ethical approval:

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent:

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflict of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation:

The authors confirms that there was no use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- First human infection case of monkey B virus identified in China, 2021. China CDC Wkly. 2021;3:633.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acute ascending myelitis following a monkey bite, with the isolation of a virus capable of reproducing the disease. J Exp Med. 1934;59:115-36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Complete sequence and comparative analysis of the genome of herpes B virus (Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1) from a rhesus monkey. J Virol. 2003;77:6167-77.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Questioning the extreme neurovirulence of monkey B virus (macacine alphaherpesvirus 1) Adv Virol. 2018;2018:5248420.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encephalomyelitis due to infection with herpesvirus simiae (herpes B virus); A report of two fatal, laboratory-acquired cases. N Engl J Med. 1959;261:64-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A fatal B virus infection in a person subject to recurrent herpes labialis. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;79:743-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Monkey-bite encephalomyelitis; Report of a case; With recovery. Br Med J. 1958;2:22-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- B virus: Its current significance; Description and diagnosis of a fatal human infection. Am J Hyg. 1958;68:242-50.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Occupational infection with virus B of monkeys. JAMA. 1962;179:804-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The simian herpesviruses In: The herpesviruses. New York: Academic Press; 1973. p. :389-426.

- [Google Scholar]

- Herpes B Virus encephalomyelitis presenting as ophthalmic zoster. A possible latent infection reactivated. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79:225-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- B Virus (herpesvirus simiae) infection in humans: Epidemiologic investigation of a cluster. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:833-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human infection with B virus following a needlestick injury. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:288-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatal Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1 (B virus) infection following a mucocutaneous exposure and interim recommendations for worker protection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:1073-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and management of human B virus (herpesvirus simiae) infections in Michigan. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:33-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpesvirus simiae (B virus): Replication of the virus and identification of viral polypeptides in infected cells. Arch Virol. 1987;93:185-98.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biology of B virus in macaque and human hosts: A review. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:555-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- B virus, herpesvirus simiae: Historical perspective. J Med Primatol. 1987;16:99-130.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transmission of B virus infection between monkeys especially in relation to breeding colonies. Lab Anim. 1984;18:125-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- B virus (herpesvirus simiae) In: The viruses. The herpesviruses. Boston: Springer; 1983. p. :385-428.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1 (B virus) infection and shedding in a large breeding cohort of rhesus macaques. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:257-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excretion of B virus in monkeys and evidence of genital infection. Lab Anim. 1984;18:65-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- B-virus (Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1) infection in humans and macaques: Potential for zoonotic disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:246-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpes B virus infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:399-403.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid identification of herpesvirus simiae (B virus) DNA from clinical isolates in nonhuman primate colonies. J Virol Methods. 1986;13:55-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Replication of simian herpesvirus SA8 and identification of viral polypeptides in infected cells. J Virol. 1984;50:316-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Production of herpes B virus recombinant glycoproteins and evaluation of their diagnostic potential. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:620-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid detection of monkeypox virus and monkey B virus by a multiplex loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay. J Infect. 2023;86:e114-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quantitative real-time PCR for detection of monkey B virus (Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1) in clinical samples. J Virol Methods. 2003;109:245-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories (5th ed). United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health; 2009. p. :205-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for prevention of and therapy for exposure to B virus (Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1) Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1191-203.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]