Translate this page into:

Aggressive angiomyxoma in pregnancy: A rare and commonly misdiagnosed entity

Address for correspondence: Dr. Kamal Malukani, 601, Akansha Apartment, Sri Aurobindo Medical College Campus, Indore-Ujjain Highway, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: kamal.malukani@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM) is an uncommon mesenchymal tumor that predominantly involves the pelvis and perineum of young females. It is often clinically mistaken for more common superficial lesions such as vaginal cysts, labial cysts, and lipomas. A review of the medical literature reveals very few cases of AAM reported in pregnancy. We describe a rare case of AAM in pregnancy, clinically misdiagnosed as prolapsed cervical fibroid.

Keywords

Aggressive angiomyxoma

mesenchymal tumors

pregnancy

Introduction

Aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm of vulvo-perineal region and usually found in women of reproductive age group.[1] It is a slow-growing, low-grade neoplasm but is locally infiltrative, and relapse has been reported in about 30%–40% of cases even after many years of complete resection.[2] Rarely, AAM can metastasize to lungs, peritoneum, and lymph nodes.[3]

Only a few cases of AAM coexistent with pregnancy are reported in medical literature.[45] AAM grows to a huge size during pregnancy which may be due to its hormone dependency as suggested by estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor (PR) positivity.[6] AAM may be clinically misdiagnosed as Bartholin cyst, lipoma, labial cyst, Gartner's duct cyst, levator hernia or sarcoma, and condyloma lata, and rate of misdiagnosis is as high as 80%.[7]

Case Report

A 24-year-old, 17-week pregnant female (G2P1L1), married for 5 years, presented with bleeding per vagina for 3 days. She also complained of huge mass coming out of vagina, difficulty in walking, and pain in abdomen and lower back. There was no history of fever, weight loss, trauma, bowel or bladder disturbance, and use of any contraceptive. Her menstrual history and past history were unremarkable. Local examination showed a large pedunculated, well-circumscribed, ulcerated mass coming out of the vagina.

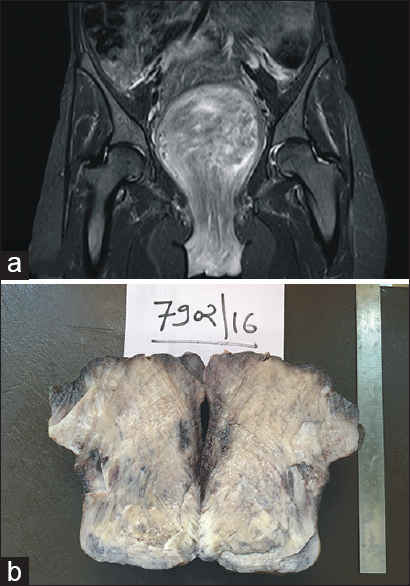

Ultrasound of abdomen showed bulky anteverted uterus, measuring 9.6 cm × 7.6 cm × 5.4 cm. Prominent heterogeneous endometrium (25 mm) with few small echogenic foci and small pockets of collection were favoring retained products of conception. Furthermore, there was a large solid mass measuring 11.4 cm × 11.3 cm × 9.95 cm in the cervical region, protruding into and outside the vagina. On magnetic resonance imaging, the mass exhibits hyperintense signal on T2 and hypointense on T1 with multiple specks of T1 hyperintensity within, suggestive of pedunculated prolapsed fibroid [Figure 1a].

- (a) Magnetic resonance imaging: mass exhibits hyperintense signal on T2 and hypointense signals on T1 with multiple specks of T1 hyperintensity. (b) Photograph showing solid, homogeneous gray-white mass with glistening appearance

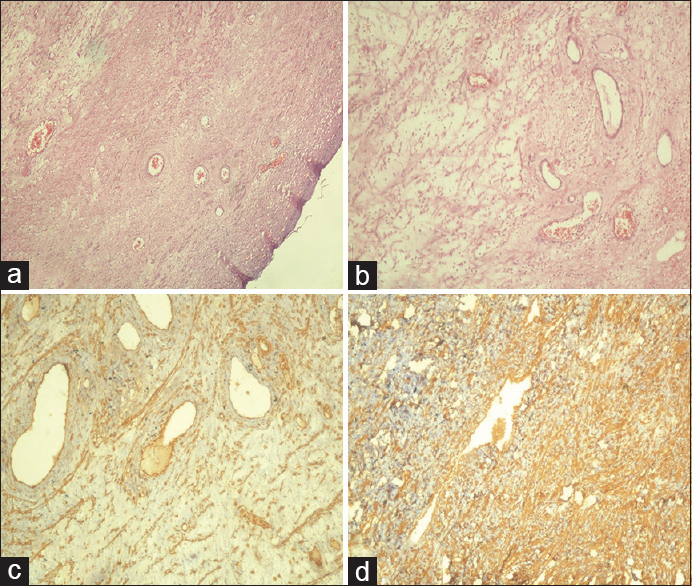

A clinical diagnosis of spontaneous incomplete abortion with prolapsed cervical fibroid was made, considering that pedunculated mass was excised and uterine curettage was done. Histology of curettage material revealed chorionic villi and trophoblastic tissue. On gross examination, mass was soft to firm and external surface shows congestion. Cut surface was a solid, homogeneous gray-white mass with glistening appearance [Figure 1b]. On microscopy, the tumor composed of admixture of loose fibroareolar tissue with numerous variable-sized vessels and round-to-stellate reticulum cells on myxoid background. Surface was partly lined by stratified squamous epithelium of vagina with areas of ulceration, hemorrhage, and mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate [Figure 2a and b]. On immunohistochemistry, tumor was positive for ER and vimentin [Figure 2c and d] and negative for PR and S-100.

- (a and b) Photomicrographs showing tumor composed of admixture of loose fibroareolar tissue with numerous variable-sized vessels and stellate reticulum cells on myxoid background (H and E, ×40). (c) Photomicrograph showing positive nuclear staining for estrogen receptors in immunohistochemistry. (d) Photomicrograph showing positive nuclear staining for vimentin in immunohistochemistry

Discussion

AAM was first described by Steeper and Rosai in 1983.[1] The term “aggressive” denotes its propensity for local aggression and recurrence after excision even with negative margins.[8] Sometimes, in view of operative morbidity, partial excision may be done. On computed tomography (CT), AAM has well-defined margins with attenuation less than that of muscle. The attenuation on CT scan and high signal intensity on magnetic resonance imaging are likely to be related to the high water content and loose myxoid matrix of AAM.[5] Superficial angiomyxoma, angiomyofibroblastoma, cellular angiofibroma, and smooth muscle tumor should also be considered as its differential diagnosis. AAM has thick-walled vessels which are less numerous than thin-walled vessels in angiofibroblastoma. Cells of AAM express vimentin, desmin, and smooth muscle antigen and may express estrogen and PRs but are negative for S-100.[9] Hormonal manipulation with tamoxifen, raloxifene, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist analogs has been attempted. These have been shown to reduce the size of tumor and may help in complete excision and in the treatment of recurrence. A gene in the region 12q13–15, called high-mobility group protein isoform I-C (HMGI-C), which encode protein involved in the transcription, has a role in pathogenesis of this tumor. Detection of HMGI-C using immunohistochemistry with anti-HMGI-C antibody may potentially be a useful marker for microscopic residual disease.[10]

Conclusion

When pregnant female presents with painless, soft vulvo-perineal mass, a high index of suspicion for AAM should always be kept in mind. Diagnosis is not at all clinical; thus, cases may present as pedunculated, prolapsed cervical fibroid. Due to its high rate of local recurrence, wide local excision and long-term follow up are necessary.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum. Report of nine cases of a distinctive type of gynecologic soft-tissue neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:463-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressive angiomyxoma of vulva recurring 8 years after initial diagnosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280:485-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressive angiomyxoma: A second case of metastasis with patient's death. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1072-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva in pregnancy: A case report and review of management options. MedGenMed. 2007;9:16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressive angiomyxoma of pelvic parts exhibits oestrogen and progesterone receptor positivity. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:603-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva and vagina. A common problem: Misdiagnosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;112:114-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressive angiomyxoma in females: Is radical resection the only option? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:216-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vulvovaginal soft tissue tumours: Update and review. Histopathology. 2000;36:97-108.

- [Google Scholar]