Translate this page into:

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Shigella isolates in a tertiary healthcare center

Address for correspondence: Dr. Anitha Madhavan, Department of Microbiology, Government TD Medical College, Alappuzha, Kerala, India. E-mail: anitha_anoop@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Shigellosis is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in children in developing countries. To the best of our knowledge, there is no published data in the study area on the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and prevalence of Shigella species among diarrheagenic cases. Therefore, a retrospective analysis was done to find the Shigella serotypes, common age group affected, and antimicrobial resistance pattern of Shigella isolates in South Kerala

METHODS:

Stool samples collected from cases of dysentery and diarrhea from January 2011 to December 2016 were processed. Standard bacteriological methods were used to isolate, identify, and determine the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Shigella isolates. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 16.

RESULTS:

Among 1585 stool samples, 48(3%) yielded Shigella. The most common serogroup isolated was Shigella sonnei (62.5%) followed by Shigella flexneri. Of 48 isolates, 44(91.6%) isolates were found to be multidrug resistant. Over the 5-year period, the isolates show 100% resistance to nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, and cotrimoxazole. Eight isolates were found to be resistant to ceftriaxone and cefotaxime. The presence of Extended spectrum betalactamase (ESBL) was phenotypically confirmed in five isolates.

CONCLUSION:

Even though S. flexneri is the most common Shigella-causing diarrhea, S. sonnei was found to be the most important species responsible in our study. Multidrug resistance was common (91.6%) and the most common multidrug resistance profile was ampicillin-nalidixic acid-cotrimoxazole-ciprofloxacin. Regular monitoring of antibiotic susceptibility pattern including detection of beta lactamases should be done in all microbiology laboratories. Guidelines for therapy should be monitored and modified based on regional susceptibility reports.

Keywords

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern

multidrug resistance

retrospective analysis

Shigella dysentery

Introduction

Shigellosis is a global public health problem. Epidemiological reports have shown that shigellosis is responsible for approximately 165 million cases annually, of which 98.8% are in developing countries.[1] The primary mode of transmission of Shigella species is by direct contact with an infected person and fomites or by eating contaminated food and water. No individual is immune to shigellosis, but certain individuals are at increased risk. Children <5 years of age contribute to nearly 69% of cases.[2] In developing countries, majority of Shigella infections is due to endemic shigellosis. The diagnosis of shigellosis is made by culture isolation of Shigella from feces or rectal swabs. Intestinal infections with Shigella can be managed with rehydration; however, antibiotics have proven to reduce intensity, duration, and prevent lethal complications. Empiric antimicrobial therapy requires knowledge of the local antibiogram of circulating Shigella strains. Especially important is the awareness of the global emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Shigellae, notably the increasing resistance to third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones and most recently to azithromycin.[34]

To our knowledge, no reports exist regarding the antibiotic resistance pattern of Shigella isolates in Kerala. This study was carried out to find the Shigella serotypes, common age group affected and antimicrobial resistance pattern of Shigella isolates in our region.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis was done on Shigella strains isolated from stool culture of patients with diarrhea and dysentery attending our hospital from January 2011 to December 2016. The study was conducted in clinical microbiology laboratory at a tertiary healthcare teaching hospital. The ethical committee of the institute approved the study.

A total of 1585 freshly collected stool samples received in the laboratory were inoculated on MacConkey agar (MA)/deoxycholate citrate agar (DCA), bile salt agar, and selenite F broth without delay for isolating Salmonella and Shigella.[5] Alkaline peptone water broth was used in suspected cases of cholera. The inoculated plates were incubated at 37°C and examined after 24 h. Subcultures were done from selenite F broth on MA/DCA and from APW broth on bile salt agar. Nonlactose fermenting colonies were identified by standard biochemical tests and serologically confirmed by commercially available polyvalent antisera (Denka Seikan, Japan). The antibiotic susceptibility testing was done by Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (HIMEDIA) as per the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. The antibiotics used were ampicillin, cotrimoxazole, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, furazolidone, gentamicin, and ceftriaxone (Microexpress). MIC to the drugs were determined using Vitek 2. Ecoli ATCC 25922 was used for quality control in each batch. ESBL production was detected using CLSI phenotypic confirmatory test (cephalosporin/clavulanate combination disc test) and double disc diffusion test on MHA[6] (HIMEDIA).

Results

Of 1585 stool samples processed in the laboratory, Shigella was isolated from 48 cases (3%). Shigella sonnei was the predominant serotype n = 30 (62.5%) isolated followed by Shigella flexneri n = 18 (37.5%). Although all age groups are susceptible to Shigella infection, the common age group affected belonged to 0–5 years (56.25%) with male predominance.

Of 48 isolates, 44 (91.6%) isolates were found to be multidrug resistant. Eleven isolates were resistant to six of the seven antibiotics tested [Table 1].

When comparing the resistance pattern of serotypes obtained, S. sonnei showed highest resistance to cotrimoxazole (96%), ciprofloxacin (90%), and almost 100% resistance to nalidixic acid. On the other hand, S. flexneri showed higher resistance to ampicillin (83.3%) than S. sonnei [Table 2].

MIC of various drugs tested by VITEK2 were as follows; ciprofloxacin ≥4, nalidixic acid ≥32, cotrimoxazole ≥320, ampicillin ≥32, ceftriaxone ≥64.

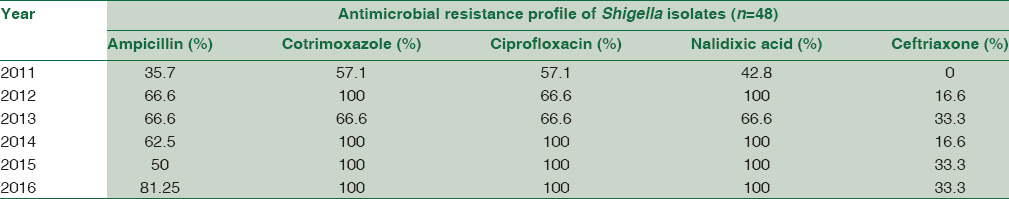

Over the 5-year period, resistance of the isolates to ampicillin, cotrimoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and nalidixic acid increased from 35.7% to 81.25%, 57.1% to 100%, 57.1% to 100%, and 42.8% to 100%, respectively [Table 3].

Discussion

Our study highlights the importance of multidrug-resistant Shigella as an enteric pathogen in both children and adults. In the present study, the rate of isolation of Shigella species is 3%. This rate is similar to studies by Taneja et al.[7] Higher rates of isolation have been reported by Nair et al. from Kolkata (6.1%).[8] Overall isolation rates reported from the country vary from 3 to 6%.[9]

In endemic regions of the developing countries, shigellosis is predominantly a pediatric disease. Although infectious diarrhea due to Shigella species is self-limiting in many cases, many experts believe that patients with positive stool cultures for Shigella species should be treated to shorten the duration of clinical symptoms and decrease fecal excretion of the organism to minimize transmission. Therefore, in children with suspected Shigella species infection, empiric antibiotic therapy is usually administered while awaiting for the stool culture and susceptibility results. Many patients often experience symptomatic relief even before the results are available. In our study, the age distribution of patients who were positive for Shigella ranged from 6 months to 65 years, with a mean age of 11.66 years ± 1.62 months. The most frequent age group affected belonged to 0–5 years (56.25%), followed by the age group 6–10 years (20.8%) [Table 5]. In literature, majority of Shigella isolates are from the pediatric population where 70% of infections occur in children <15 years.[10] In the present work, children accounted for 87.5% of Shigella-positive patients.

Shigella dysenteriae and S. flexneri are the predominant species isolated in the tropics. Clinically, S. dysenteriae I is associated with large outbreaks and severe disease. S. flexneri is the most prevalent serogroup in other studies from India.[111213] The most common Shigella serotype obtained in our study was S. sonnei (62.5%). So far, there are no reports of such high incidence of S. sonnei reports from India. S. sonnei occur more frequently in industrialized countries with a milder course. The predominant species has shifted from S. flexneri to S. sonnei in Thailand, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka possibly due to improved socioeconomic developments in the country.[1415] Our study substantiates such a scenario developing in southern regions of India also.

Shigella infections are commonly associated with poor sanitation and limited access to clean water. The rate of Shigella isolation was found to decrease from 2011 to 2013 [Table 4] which could be due to improved public health measures, whereas the isolation rates showed an increase in subsequent years. This may be due to lack of continuing efforts by health authorities to improve sanitation.

Antimicrobial therapy of Shigella infections hastens the clinical recovery, prevents complications, and stops the dissemination of the bacteria back into the community. Fluoroquinolones were recommended as the drug of choice by the WHO in1990.[16] Ciprofloxacin proved to be highly effective in the treatment of shigellosis. The emergence of MDR Shigella is possibly due to overuse and misuse of this agent for diarrhea and urinary tract infections. The resistance rate of Shigella isolates to ciprofloxacin in our work came to be 85.4% [Table 2]. Another study from Kolkata reported 90% resistance to quinolones.[17] Higher resistance rates have been reported from other parts of India also.[18] Fluoroquinolones are thus no longer the preferred group of drugs for managing shigellosis in India.

Overall, 17.02% of Shigella isolates were found to be resistant to at least one of the third-generation cephalosporin tested, ceftriaxone and cefotaxime. Among the S. sonnei isolates, 20% were found to be resistant, whereas S. flexneri showed 11.76% resistance to either cefotaxime or ceftriaxone. Studies from Southeast Asia have reported the resistance of Shigella spp. to cephalosporins at 2.0%–5.2%.[317] However, there was a higher percentage of cephalosporin resistance (17.02%) in our study. A large multicenter study in eight Asian countries (Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Philippines, Hong Kong, and Sri Lanka) from 2001 to 2004 also observed increased resistance to ceftriaxone (5%) in Shigella isolates.[3] The high resistance observed in our isolates may not reflect the true prevalence of cephalosporin resistance in Shigella sp. in the community, as ours is a tertiary care referral center that receives partially or completely treated cases.

Analysis of antibiotic susceptibility data shows a gradual increase in resistance pattern of ciprofloxacin from 57.1% to 100% during the 5-year period; fluctuating but persistent resistance to ampicillin; 35.7% to 81.25%. Cotrimoxazole and nalidixic acid also showed 100% resistance from 2014 to 2016 [Table 3]. Higher cotrimoxazole resistance compared to ampicillin was reported by Kumar et al. also.[19] The isolates obtained also showed maximum resistance to nalidixic acid (100%). Similar resistance pattern was reported by Tejashree et al. and Nath and Saikia.[20] Although ceftriaxone resistance was not detected in 2011, the resistance rate was found to be the same during 2015–2016 (33.3%). This fluctuating resistance to antimicrobials may be due to plasmid-mediated carriage of the resistance determinants within members of Enterobacteriaceae family. In our study, the isolates exhibited comparatively lower resistance to furazolidone (43.7%) and gentamicin (33.3%), which support the findings of the study by Taneja et al.

When the resistance rates of the serotypes were compared, S. sonnei strains were found to be more resistant than S. flexneri strains. Thus, MDR S. sonnei strains which were reported only in Israel, USA, and other developing countries,[21] has emerged as the predominant serotype in our region. In this study, multiple drug resistance to as many as six antimicrobials were observed with 91.6% isolates being multidrug-resistant strains [Table 1]. Eight strains of multidrug-resistant Shigella (S. sonnei n = 6 and S flexneri n = 2) showed resistance to third-generation cephalosporins, ceftriaxone and cefotaxime. The MIC values obtained for ceftriaxone (VITEK 2) was also significantly high (MIC ≥ 64). Five isolates (S. sonnei n = 3 and S. flexneri n = 2) were phenotypically confirmed to be ESBL producers. We were not able to revive the other strains. All ceftriaxone-resistant isolates (n = 8) in our study were susceptible to piperacillin tazobactam, cefaperazonesulbactum, and imipenem. The first ESBL-producing ceftriaxone-resistant S. sonnei strain was isolated from a fecal sample of a child from Ho Chi Minh City, who had severe dysentery, in May 2007.[22] ESBL-carrying Shigella are being increasingly reported from different parts of the world.[2324] Of eight ceftriaxone-resistant cases, four were on ceftriaxone, which was stopped after 48 h of receiving antibiotic sensitivity report and managed symptomatically as the symptoms were mild. One case was discharged at request and lost to follow-up. The other three cases were discharged on cefixime (not included in sensitivity report). All the cases improved clinically on follow-up.

Since azithromycin is now recommended by the AAP as a therapeutic option for the treatment of Shigella species infections in children where the susceptibility of the isolate is unknown or is known to be resistant to ampicillin or cotrimoxazole, the need for clinically validated susceptibility breakpoints and data supporting its efficacy in both children and adults is critical. Moreover, there are currently no clearcut CLSI guidelines or susceptibility breakpoints for interpretation of azithromycin susceptibility for Gram-negative bacteria including Shigella species. There is only one other published study evaluating the efficacy of azithromycin for the treatment of shigellosis, which was conducted in seventy adult Bangladesh men.[25] Further studies are needed to define the role of azithromycin in the treatment of bacterial diarrhea due to Shigella species.

Conclusion

The study highlights on the prevalence of MDR Shigella in south Kerala with the predominant serogroup being S. sonnei. In milder cases, especially in children, choosing the optimal oral drug is a problem and should be based on local epidemiological data. The prescription of cefixime and ceftriaxone as empirical drugs leads to the emergence of ESBL-producing Shigella strains. Azithromycin and piperacillin tazobactam can become treatment options in treating MDR strains. Physicians should be aware of the high-antimicrobial resistance rates among Shigella. Continuous monitoring of MDR strains along with serotyping is very important to know the changing susceptibility pattern as well as cyclical changes of the serogroup in various regions of the country.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global burden of Shigella infections: Implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:651-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial susceptibility of Shigella isolates in eight Asian countries, 2001-2004. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008;41:107-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shigella antimicrobial drug resistance mechanisms, 2004-2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1083-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ananthanarayanan and Panikers Textbook of Microbiology (9th ed). Himayatnagar, Hyderabad: University Press; 2013. p. :288.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: 21st Informational Supplement M100-S21. Vol 31. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2011. p. :48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cephalosporin-resistant Shigella flexneri over 9 years (2001-2009) in India. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1347-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changing epidemiology of shigellosis and emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant Shigellae in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:678-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging trends in the etiology of enteric pathogens as evidenced from an active surveillance of hospitalized diarrhoeal patients in Kolkata, India. Gut Pathog. 2010;2:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A five-year antimicrobial resistance pattern of Shigella isolated from stools in the Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Trop Doct. 2008;38:43-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The recent trends of shigellosis: A JIPMER perspective. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1474-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging trends in the etiology and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of enteric pathogens in rural Coastal India. Int J Clin Med. 2014;5:425-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of enteric pathogens in a tertiary hospital. Transworld Med J. 2013;1:69-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- A multicentre study of Shigella diarrhoea in six Asian countries: Disease burden, clinical manifestations, and microbiology. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e353.

- [Google Scholar]

- Achanging picture of shigellosis in Southern Vietnam: Shifting species dominance, antimicrobial susceptibility and clinical presentation. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:204.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Control of Shigellosis, Including Epidemics due to Shigella dysenteriae type 1. WHO Document Production Services. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. p. :11-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subtype prevalence, plasmid profiles and growing fluoroquinolone resistance in Shigella from Kolkata, India (2001-2007): A hospital-based study. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:1499-507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial resistance in Shigella – Rapid increase and widening of spectrum in Andaman Islands, India. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:365-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Shigella in stool samples in a tertiary healthcare hospital of Punjab. CHRISMED J Health Res. 2014;1:33-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Drug resistant Shigella flexneri in and around Dibrugarh, North-East India. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:183-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent trends in the epidemiology of Shigella species in Israel. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:897-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical implications of reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones in paediatric Shigella sonnei and Shigella flexneri infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:807-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extended spectrum beta-lactamase production in Shigella isolates – A matter of concern. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:76-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-mediated third-generation cephalosporin resistance in Shigella isolates in Bangladesh. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:846-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of shigellosis: V. Comparison of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:697-703.

- [Google Scholar]