Translate this page into:

Antimicrobial Resistance in Enterobacteriaceae Bacteria Causing Infection in Trauma Patients: A 5-Year Experience from a Tertiary Trauma Center

Address for correspondence: Purva Mathur, MD, Department of Laboratory Medicine, JPNATC, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi 110029, India (e-mail: purvamathur@yahoo.co.in).

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction

Multiple drug resistance emergences among bacteria at an alarming rate worldwide are posing a serious threat to the treatment benefits that have been achieved with antibiotics. This crisis is due to the inappropriate and overuse of existing antibiotics. We evaluated the antimicrobial resistance pattern of Enterobacteriaceae pathogens isolated from intensive care units (ICUs), wards, and outpatient department (OPD) patients.

Objectives

The aim of the study is to determine the antimicrobial resistance pattern in bacteria of Enterobacteriaceae family.

Material and Methods

This is a retrospective study conducted at a tertiary care level-1 trauma center in the capital city of India. We collected all the retrospective data of 5 years from the laboratory information system software of the microbiology laboratory. The retrospective data included patients’ details, samples detail, organism's identification, and their antimicrobial susceptibility testing, done by Vitek2 compact system and disk diffusion test according to each year's Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. This study included the interpretation of zone diameters and minimum inhibitory concentrations of all isolates according to CLSI guidelines, 2018.

Results

Among all the Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella spp. was the most commonly isolated pathogen, followed by Escherichia coli and Enterobacter spp. in ICUs and wards, while in OPD patients E. coli was the most commonly isolated pathogen, followed by Klebsiella spp. and Enterobacter spp. Enterobacteriaceae isolates remained resistant to all classes of cephalosporins in all settings. In addition, β lactam and β-lactamase inhibitor remained less effective. Carbapenems showed less resistance than quinolones and aminoglycosides. Among the different antimicrobial agents, tigecycline proved most effective in all settings; however, it showed more resistance than other studies.

Conclusion

Tigecycline proved effective among different multidrug resistance bacteria. Multidrug resistance in bacteria leads to prolonged hospital stays as well as makes the treatment less cost effective. Proper and judicious use of antimicrobials is the need of the hour.

Keywords

tigecycline

Vitek2

disk diffusion

Enterobacteriaceae

Klebsiella spp.

Escherichia coli

antibiotic resistance

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance is a great threat to patient care. This antibiotic resistance not only increases the total cost of effective treatment but also is associated with a substantial increase in morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients.[1-4] Nosocomial infections are one of the main causes of death in trauma patients, and bacteria belonging to family Enterobacteriaceae are the most prominent causative agents of these nosocomial infections.[2,5] Beta lactam antibiotics are usually the first line of treatment used against the infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae, however, with time these bugs have evolved by producing extended spectrum of β lactamases (ESBL). The first ESBL producing Enterobacteriaceae reported from Germany in 1983 and since then, their incidence has been reported to be increasing rapidly worldwide.[6] In 1994, the first KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate was reported in Japan, which conferred resistance to carbapenems.[7] In 1999, Martínez-Martínez et al found that the combination of porin loss and the presence of plasmid-mediated β lactamases resulted in carbapenem resistance.[8] New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM-1) producing Enterobacteriaceae are resistant to all β-lactams and carbapenemens.[9] Unfortunately, today these bugs have started to confer resistance against colistin, which is the last resort against these highly resistant gram-negative pathogens.[10-12]

This study is unique because of its large sample size, different source of samples, patients admitted to different settings (intensive care unit [ICU], ward, and outpatient department [OPD]) and use of wide range of antimicrobial agents. Very few authors have reported the study with such a large sample size. The present study would help in understanding the antimicrobial resistance pattern in Enterobacteriaceae pathogens isolated from different settings of level-1 trauma center over a period of 5 years.

Materials and Methods

Study Period and Place

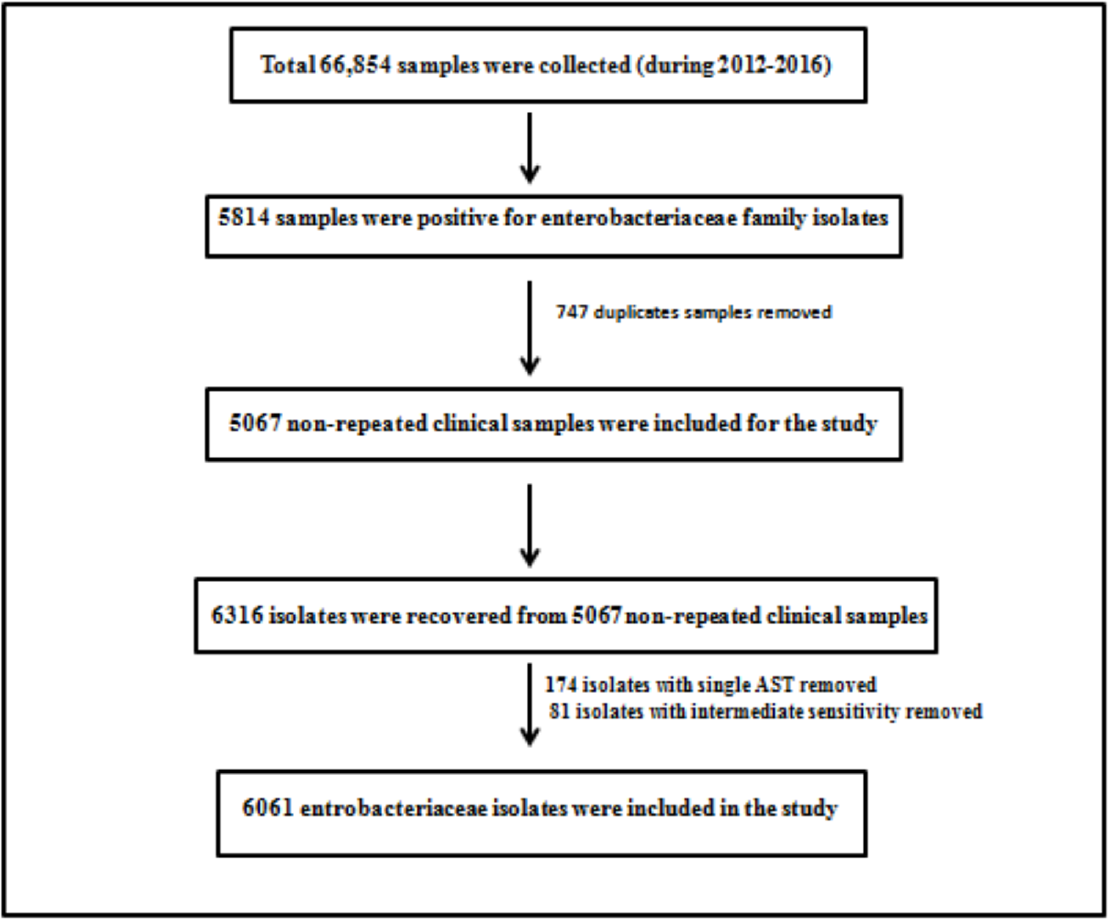

Retrospective 5 years data (January 2012 to December 2016) was collected from laboratory information system software of microbiology laboratory of 186 bedded tertiary apex trauma center, New Delhi. A total of 6,061 isolates belonging to family Enterobacteriaceae were recovered from 5,067 nonrepeated clinical samples. These clinical isolates were recovered from patients’ clinical samples received during this study period, namely, blood, urine, body fluid, bone and tissue, tip culture, pus/wound and swab, and respiratory samples. Duplicate samples were excluded from the study. All organisms were not subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) by both methods. Therefore, for accuracy, only those isolates which were subjected to AST by both methods constituted the analysis. Intermediate sensitive isolates were not included in the study. ►Fig. 1 shows the exclusion and inclusion criteria.

- Exclusion and inclusion criteria included in the study.

Bacterial Identification

All the samples were processed as per standard microbiological methods. Bacterial isolates were identified to species level by the Vitek2 compact identification system (Biomeriux, France).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

The antimicrobial susceptibility testing of all isolates was done by the disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar. Apart from this, the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were also determined by the Vitek2 compact system (using AST GN cards; Biomeriux, France). The interpretation of zone diameters and MICs was done according to each year's CLSI guidelines.

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was taken as the control strains. The following antimicrobials (Himedia, India) were tested: ceftazidime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), cefoxitin (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), piperacillin (100 µg), piperacillin-tazobactam (100/10 μg), ticarcillin-clavulanate (75/10 μg), cefoperazone-sulbactam (75/30 μg), cefepime-tazobactam (30/10 µg), ceftriaxone- sulbactam (30/15 µg), imipenem (10 μg), meropenem (10 μg), ertapenem (10 μg), amikacin (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), netilmicin (30 μg), tobramycin (10 μg), tetracycline (30 µg), Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1.25/24 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), levofloxacin (5 μg), tigecycline (15 μg), nitrofurantoin (300 μg), and chloramphenicol (30 μg).

We interpreted the zone diameters and MICs of the isolates as per CLSI recommendations, 2018.[13]

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States, version 15.0). The decreased resistance percentage was reported as the resistance percentage difference between the first year (2012) and the last year (2016) of the study.

Results

During the study, a total of 5,067 positive samples were included. The mean age of the patients from whom the samples were received was 32 years (range ± standard deviation [SD]: 1 to 87 ± 15.1 years). In male patients, the mean age was 46 years (range ± SD: 1 to 112 ± 27.11 years) whereas, in female patients, the mean age was found to be 44.5 years with a range of 2 to 96 ± 26.84 years). The difference of the means of the age in male and female patients was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.002, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.9481–4.2187).

Samples received from ICU (1,472, 29%), wards (2,714, 53.6%), and OPD (881, 17.4%) admitted patients were included in this study. Maximum number of Enterobacteriaceae isolates were obtained from patients admitted to general surgical ward (1,254, 25%) followed by neurosurgical ward (1,242, 25%), neurosurgical ICU (739, 15%), polytrauma ICU (733, 14%), and orthopaedics ward (218, 4%). The outpatients contributed about (881) 17% of the samples.

The samples included in our study were blood, urine, body fluid, respiratory samples, bone and tissue, pus/wound and swab, and tip culture. ►Table 1 shows the distribution of clinical samples included in this study. Blood culture yielded the maximum number of isolates (1,663, 33%), followed by pus/wound and swab (1,317, 26%), urine (849, 17%), respiratory samples (761, 15%), body fluid (268, 5%), bone and tissue (135, 3%), and tip culture samples (74, 1%).

| Samples (N = 5,067) | |

|---|---|

| N (%) | |

| Blood | 1,663 (33%) |

| Pus/wound + swab | 1,317 (30%) |

| Urine | 849 (17%) |

| Respiratory | 761 (15%) |

| Body fluid | 268 (5%) |

| Bone + tissue | 135 (3%) |

| Tip culture | 74 (1%) |

aN, total number of isolates.

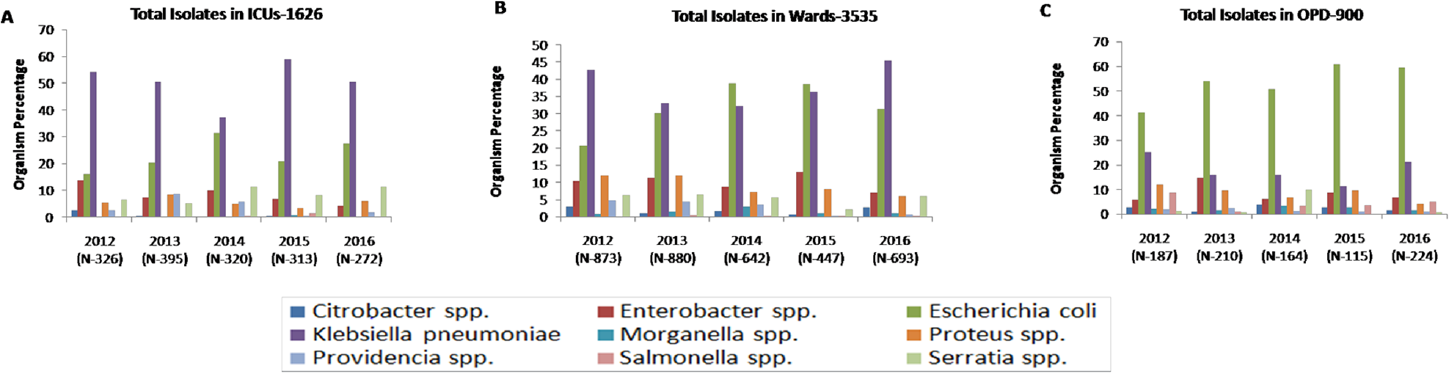

The maximum number of Enterobacteriaceae isolates recovered are from wards (3,535, 58.3%), followed by ICUs (1,626, 26.8%), and OPDs (900, 14.8%). In ICUs, Klebsiella spp. (815, 50.1%) was found to be the most predominant Enterobacteriaceae followed by E. coli (371, 22.8%) and Enterobacter spp. (135, 8.3%) throughout the study period (►Fig. 2A). In wards also, we found the same pattern except in 2014 and 2015 where E. coli was the most prominent (►Fig. 2B). In OPD, E. coli was the most predominant Enterobacteriaceae (476, 52.8%), followed by Klebsiella spp. (166, 18.4%) and Enterobacter spp. (77, 8.6%) (►Fig. 2C). For the purpose of conciseness, we concentrate on only predominant Enterobacteriaceae isolates, i.e., Klebsiella spp. and E. coli.

- Yearly distribution of Enterobacteriaceae isolates in (A) ICUs, (B) wards, and (C) OPDs. ICU, intensive care unit; OPD, outpatient department.

In ICU settings, both E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates showed more than 80% resistance against cephalosporins and quinolones. E. coli isolates showed maximum resistance to ciprofloxacin (94.6%), followed by ceftazidime and piperacillin (92%), ticarcillin-clavulanate (84.6%), and levofloxacin (84%). Among carbapenems, E. coli isolates showed more resistance against ertapenem (56%), followed by meropenem (36.3%) and imipenem (19.4%). The resistance against amikacin and chloramphenicol in E. coli isolates was observed in 38 and 29%, respectively. Among quinolones, Klebsiella spp. isolates showed maximum resistance to ciprofloxacin (85%), followed by levofloxacin (77.8%). These isolates also showed resistance against carbapenems; the resistance pattern was the same as observed in E. coli isolates, i.e., ertapenem (69%) > meropenem (67.3%) > imipenem (59%). Both E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates showed least resistance to tigecycline; Klebsiella spp. isolates showed 16% resistance, while E. coli isolated showed less than 1% resistance. All the urine isolates were resistant (98–100%) to nitrofurantoin. The year-wise resistance pattern against different antibiotics of Enterobacteriaceae in ICU settings is given in ►Table 2. In wards, E. coli showed 90% resistance to cephalosporins, 84% resistance to ceftazidime, and 81% resistance to levofloxacin. Among aminoglycosides, highest resistance was observed against gentamycin (55%), followed by tobramycin (41%) and amikacin (27%). Among carbapenems, maximum resistance was observed against ertapenem (46.8%), followed by meropenem (31.8%) and imipenem (16.1%). Klebsiella spp. isolates showed 92% resistance to ceftazidime, 89% to ciprofloxacin, and 79% to levofloxacin. Among aminoglycosides, Klebsiella spp. showed highest resistance against gentamycin (80%), followed by amikacin (73%). Among carbapenems, resistance against both ertapenem and meropenem was 67% and against imipenem was 53%. The year-wise resistance pattern against different antibiotics of Enterobacteriaceae in wards settings is given in ►Table 3.

| Organism name | Year | AMK, N (%) | CEFEP, N (%) | CEFEPTAZ, N (%) | CEFOSUL, N (%) | CEFOT, N (%) | CEFOX, N (%) | CEFTAZ, N (%) | CEFTRX, N (%) | CEFTRXSUL, N (%) | CHL, N (%) | CIPRO, N (%) | ERTA, N (%) | GENTA, N (%) | IMI, N (%) | LEVO, N (%) | MERO, N (%) | NETIL, N (%) | PIP, N (%) | PIPTAZ,N (%) | TETRA, N (%) | TIC, N (%) | TICLAV,N (%) | TIG, N (%) | TOBRA, N (%) | TMZ, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrobacter spp. | 2012 (8) | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | NA | 8 (100) | NA | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | NA | 2 (25) | 8 (100) | 1 (14) | 8 (100) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | 0 | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | 0 | 8 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | |

| 2014 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2015 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 1 (100) | |

| 2016 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Enterobacter spp. | 2012 (44) | 39 (88) | 39 (88) | NA | 38 (86) | NA | IR | 40 (91) | 40 (91) | NA | 30 (69) | 38 (86) | 40 (92) | 39 (89) | 33 (75) | 37 (84) | 37 (82) | 38 (86) | 40 (91) | 38 (86) | 20 (45) | 43 (97) | 38 (87) | 4 (9) | 43 (97) | NA |

| 2013 (28) | 13 (46) | 19 (67) | 13 (46) | 18 (64) | 15 (53) | IR | 24 (86) | 19 (68) | 13 (46) | 10 (35) | 19 (68) | 12 (43) | 17 (61) | 15 (54) | 13 (46) | 17 (61) | 16 (57) | 24 (86) | 15 (52) | 14 (50) | 28 (100) | 20 (70) | 4 (13) | 28 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (31) | 20 (65) | 22 (71) | 20 (63) | 21 (67) | 23 (74) | IR | 23 (74) | 24 (77) | 23 (74) | 10 (31) | 21 (68) | 22 (71) | 23 (74) | 17 (55) | 21 (68) | 18 (58) | 21 (69) | 24 (77) | 19 (61) | 0 (0) | NA | 26 (84) | 5 (17) | NA | 24 (77.4) | |

| 2015 (21) | 8 (40) | 13 (63) | 6 (29) | 6 (29) | 14 (67) | IR | 15 (70) | 18 (88) | 8 (40) | 11 (50) | 11 (50) | 10 (46) | 13 (60) | 3 (16) | 11 (50) | 3 (15) | 13 (60) | 14 (65) | 5 (26) | 21 (100) | 0 (0) | 13 (61) | 2 (11) | NA | 10 (50) | |

| 2016 (11) | 5 (46) | 4 (36) | 6 (55) | 6 (55) | 11 (100) | IR | 6 (55) | 6 (55) | 6 (55) | 4 (36) | 6 (55) | 0 (0) | 6 (55) | 4 (36) | 6 (50) | 6 (55) | 5 (46) | 6 (55) | 6 (55) | NA | NA | 6 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Escherichia coli | 2012 (52) | 17 (33) | 39 (75) | NA | 32 (62) | NA | 35 (67) | 46 (88) | 47 (90) | NA | 10 (20) | 49 (94) | 9 (17) | 27 (52) | 11 (21) | 44 (85) | 29 (56) | 16 (30) | 51 (98) | 39 (75) | 44 (85) | 50 (96) | 35 (67) | 0 | 52 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (80) | 26 (33) | 66 (82) | 22 (28) | 37 (46) | 77 (96) | 48 (60) | 76 (95) | 73 (91) | 37 (46) | 20 (25) | 72 (90) | 21 (26) | 51 (64) | 11 (14) | 67 (84) | 41 (51) | 26 (33) | 65 (81) | 51 (64) | 70 (88) | 78 (97) | 75 (94) | 1 (1) | 80 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (100) | 33 (33) | 77 (77) | 34 (34) | 43 (43) | 94 (94) | 67 (67) | 85 (85) | 94 (94) | 48 (48) | 22 (22) | 94 (94) | 62 (62) | 62 (62) | 27 (27) | 70 (70) | 41 (41) | 33 (33) | 87 (87) | 55 (55) | NA | NA | 84 (84) | 1 (1) | NA | 83 (83.8) | |

| 2015 (65) | 32 (49) | 57 (88) | 33 (51) | 28 (43) | 65 (100) | NA | 63 (97) | 65 (100) | 46 (70) | 23 (36) | 65 (100) | 49 (76) | 50 (77) | 6 (9) | 64 (99) | 9 (14) | 34 (53) | 64 (99) | 34 (53) | NA | NA | 59 (91) | 0 (0) | NA | 47 (72.3) | |

| 2016 (74) | 34 (46) | 69 (93) | 26 (35) | 30 (40) | 71 (96) | NA | 71 (96) | 71 (96) | 44 (60) | 33 (44) | 71 (96) | 66 (89) | 60 (81) | 17 (23) | 66 (89) | 18 (24) | 36 (48) | 73 (99) | 37 (50) | NA | NA | 61 (83) | 0 (0) | NA | 56 (75) | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2012 (176) | 148 (84) | 162 (92) | NA | 162 (92) | 176 (100) | 165 (94) | 169 (96) | 171 (97) | NA | 116 (66) | 171 (97) | 128 (73) | 158 (90) | 121 (69) | 162 (92) | 144 (82) | 160 (91) | 169 (96) | 153 (87) | 118 (67) | IR | 172 (98) | 42 (24) | 174 (99) | NA |

| 2013 (199) | 167 (84) | 187 (94) | 151 (76) | 177 (89) | 195 (98) | 171 (86) | 187 (94) | 189 (95) | 159 (80) | 111 (56) | 185 (93) | 109 (55) | 169 (85) | 123 (62) | 169 (85) | 161 (81) | 165 (83) | 191 (96) | 153 (77) | 107 (54) | IR | 189 (94) | 34 (17) | 199 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (119) | 88 (74) | 104 (87) | 87 (73) | 94 (79) | 106 (89) | 95 (80) | 104 (87) | 112 (94) | 88 (74) | 48 (40) | 95 (80) | 83 (70) | 94 (79) | 71 (60) | 75 (63) | 90 (76) | 83 (70) | 105 (88) | 91 (76) | 0 (0) | IR | 106 (89) | 19 (16) | NA | 94 (79.6) | |

| 2015 (184) | 96 (52) | 166 (90) | 94 (51) | 131 (71) | 177 (96) | NA | 158 (86) | 166 (90) | 132 (72) | 101 (55) | 145 (79) | 118 (64) | 134 (73) | 75 (41) | 138 (75) | 88 (48) | 107 (58) | 169 (92) | 132 (71) | NA | IR | 160 (87) | 21 (12) | NA | 145 (80.1) | |

| 2016 (137) | 122 (89) | 126 (92) | 104 (76) | 96 (70) | 137 (100) | NA | 132 (96) | 123 (90) | 119 (87) | 92 (67) | 104 (76) | 121 (88) | 100 (73) | 90 (66) | 90 (66) | 66 (48) | 127 (93) | 136 (99) | 89 (65) | NA | IR | 117 (86) | 19 (14) | 0 (0) | 112 (82) | |

| Morganella spp. | 2012 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | IR | NA | NA |

| 2013 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | IR | NA | NA | |

| 2014 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | IR | NA | NA | |

| 2015 (2) | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 | NA | 2 (100) | IR | NA | 2 (100) | |

| 2016 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | IR | NA | NA | |

| Proteus spp. | 2012 (17) | 11 (63) | 17 (100) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | 2 (14) | 15 (88) | 17 (100) | NA | 11 (67) | 17 (100) | NA | 9 (50) | 0 (0) | 13 (77) | 9 (53) | 17 (100) | 5 (31) | 0 (0) | IR | 14 (82) | 6 (36) | IR | 17 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (33) | 13 (38) | 29 (89) | 4 (13) | 3 (9) | 24 (73) | 9 (26) | 26 (79) | 20 (61) | 4 (13) | 24 (74) | 15 (46) | 33 (100) | 18 (55) | 2 (6) | 18 (55) | 21 (64) | 28 (85) | 7 (21) | 1 (3) | IR | 33 (100) | 14 (43) | IR | 33 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (15) | 11 (73) | 12 (80) | 1 (7) | 6 (40) | 9 (63) | 5 (36) | 12 (80) | 8 (53) | 2 (13) | 12 (80) | 13 (87) | 0 (0) | 12 (80) | 6 (39) | 12 (80) | 6 (40) | 14 (93) | 6 (40) | 0 (0) | IR | NA | 8 (53) | IR | NA | 14 (93.3) | |

| 2015 (10) | 0 (0) | 3 (30) | 0 | 0 | 2 (22) | 0 | 3 (30) | 0 | 0 | 8 (80) | 3 (30) | 0 | 2 (20) | 0 | 3 (30) | 0 | 3 (30) | 0 | 6 (60) | IR | NA | 0 | IR | NA | 4 (40) | |

| 2016 (16) | 5 (31) | 3 (19) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 10 (60) | NA | 6 (38) | 7 (44) | 2 (13) | 2 (15) | 9 (56) | 0 (0) | 6 (38) | 3 (19) | 10 (60) | 1 (6) | 6 (38) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | IR | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | IR | 0 (0) | 6 (35.7) | |

| Providencia spp. | 2012 (8) | 7 (88) | 5 (57) | NA | 7 (88) | NA | 7 (86) | 7 (88) | 7 (88) | NA | 8 (100) | 4 (50) | NA | 7 (88) | 6 (75) | 4 (50) | 1 (13) | 7 (88) | 7 (88) | 6 (7.5) | IR | 6 (80) | 8 (100) | IR | 8 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (34) | 23 (68) | 23 (67) | 28 (83) | 26 (77) | 31 (92) | 20 (60) | 26 (76) | 26 (76) | 28 (83) | 23 (69) | 28 (82) | 0 (0) | 28 (82) | 9 (27) | 29 (85) | 21 (62) | 25 (74) | 22 (65) | 13 (38) | IR | 13 (38) | 27 (79) | IR | 34 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (18) | 17 (94) | 17 (94) | 13 (72) | 17 (92) | 17 (94) | 14 (78) | 18 (100) | 17 (94) | 15 (83) | 13 (71) | 17 (94) | 18 (100) | 18 (100) | 17 (94) | 17 (94) | 13 (72) | 18 (100) | 17 (94) | 17 (94) | IR | NA | 18 (100) | IR | NA | 7 (41.2) | |

| 2015 (1) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | IR | NA | 1 (100) | IR | NA | NA | |

| 2016 (4) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | IR | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | IR | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | |

| Salmonella spp. | 2012 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2013 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2014 (1) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2015 (4) | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | |

| 2016 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Serratia spp. | 2012 (21) | 17 (81) | 14 (65) | NA | 15 (71) | NA | IR | 18 (86) | 18 (86) | NA | 6 (30) | 14 (67) | NA | 8 (38) | 5 (25) | 13 (62) | 9 (45) | 14 (67) | 21 (100) | 18 (86) | 7 (35) | 18 (86) | 21 (100) | 11 (50) | 18 (86) | NA |

| 2013 (20) | 11 (55) | 12 (62) | 6 (29) | 9 (47) | 10 (50) | IR | 17 (85) | 15 (75) | 6 (29) | 2 (10) | 7 (37) | 0 (0) | 6 (30) | 4 (21) | 3 (15) | 7 (35) | 15 (75) | 15 (75) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 19 (93) | 15 (74) | 2 (11) | 18 (92) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (36) | 28 (78) | 29 (81) | 1 (4) | 5 (14) | 33 (91) | IR | 32 (89) | 30 (83) | 4 (11) | 9 (25) | 15 (42) | 12 (33) | 5 (14) | 13 (37) | 8 (22) | 9 (25) | 27 (74) | 28 (78) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 24 (67) | 8 (23) | NA | 15 (41.7) | |

| 2015 (25) | 2 (8) | 8 (32) | 4 (17) | 5 (20) | 25 (100) | IR | 12 (48) | 20 (80) | 3 (12) | 4 (16) | 8 (32) | 25 (100) | 1 (4) | 6 (22) | 3 (13) | 4 (16) | 21 (83) | 8 (32) | 7 (28) | 0 (0) | NA | 8 (32) | 4 (17) | NA | 1 (4) | |

| 2016 (30) | 26 (85) | 26 (85) | 3 (11) | 6 (19) | 27 (90) | IR | 29 (96) | 29 (96) | 19 (63) | 9 (29) | 12 (40) | 0 (0) | 8 (26) | 0 (0) | 23 (75) | 0 (0) | 29 (96) | 29 (96) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 29 (96) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: AMK, amikacin; CEFEP, cefepime; CEFEPTAZ, cefepime-tazobactam; CEFOSUL, cefoperazone-sulbactam; CEFOT, cefotaxime; CEFOX, cefoxitin; CEFTAZ, ceftazidime; CEFTRX, ceftriaxone; CEFTRXSUL, ceftriaxone-sulbactam; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIPRO, ciprofloxacin; ERTA, ertapenem; GENTA, gentamicin; IMI, imipenem; IR, intrinsic resistance; LEVO, levofloxacin; MERO, meropenem; NA, not applicable; NETIL, netilmicin; PIP, piperacillin; PIPTAZ, piperacillin-tazobactam; TETRA, tetracycline; TIC, ticarcillin-clavulanate; TIG, tigecycline; TOBRA, tobramycin; TMZ, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Note: N denotes the number of isolates.

| Organism name | Year | AMK, N (%) | CEFEP, N (%) | CEFEPTAZ, N (%) | CEFOSUL, N (%) | CEFOT, N (%) | CEFOX, N (%) | CEFTAZ, N (%) | CEFTRX, N (%) | CEFTRXSUL, N (%) | CHL, N (%) | CIPRO, N (%) | ERTA, N (%) | GENTA, N (%) | IMI, N (%) | LEVO, N (%) | MERO, N (%) | NETIL, N (%) | PIP, N (%) | PIPTAZ, N (%) | TETRA, N (%) | TIC, N (%) | TICLAV, N (%) | TIG, N (%) | TOBRA, N (%) | TMZ, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrobacter spp. | 2012 (25) | 18 (73) | 14(57) | 0 (0) | 17 (69) | 0 (0) | 18 (73) | 18 (73) | 19 (76) | 0 (0) | 15 (60) | 15 (58) | 16 (63) | 18 (73) | 13 (50) | 7 (28) | 10 (39) | 17 (67) | 19 (76) | 15 (60) | 4 (17) | 23 (92) | 21 (85) | 0 (0) | 25 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 2013 (9) | 5 (55) | 5 (55) | 6 (71) | 5 (55) | 9 (100) | 7 (82) | 6 (64) | 7 (82) | 6 (71) | 6 (71) | 5 (55) | 7 (75) | 5 (55) | 2 (27) | 2 (27) | 4 (46) | 5 (55) | 5 (60) | 5 (55) | 5 (50) | 6 (67) | 7 (73) | 0 (0) | 9 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (10) | 3 (31) | 3 (31) | 3 (31) | 4 (38) | 4 (36) | 6 (62) | 5 (50) | 4 (38) | 4 (36) | 2 (23) | 2 (19) | 6 (56) | 4 (38) | 1 (14) | 1 (13) | 1 (6) | 2 (23) | 4 (44) | 4 (38) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2015 (3) | 2 (50) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (40) | 1 (40) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 2 (60) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 1 (33) | 2 (50) | 1 (33) | 2 (50) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (18) | 5 (30) | 10 (55) | 5 (25) | 11 (60) | 18 (100) | 0 (0) | 12 (68) | 12 (68) | 12 (65) | 12 (68) | 12 (65) | 10 (55) | 7 (39) | 3 (15) | 5 (28) | 3 (17) | 7 (40) | 13 (70) | 8 (44) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (70) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (17) | |

| Enterobacter spp. | 2012 (89) | 57 (64) | 59 (66) | 0 (0) | 61 (68) | 0 (0) | IR | 68 (76) | 69 (77) | 0 (0) | 36 (41) | 60 (67) | 39(44) | 61(68) | 46 (52) | 53 (60) | 54 (61) | 58 (65) | 73 (82) | 55 (62) | 40 (45) | 75 (84) | 76 (85) | 7 (8) | 89 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 2013 (99) | 51 (52) | 57(58) | 44 (44) | 60 (61) | 70 (71) | IR | 73 (74) | 68 (69) | 58 (59) | 58 (59) | 53 (54) | 41 (41) | 58 (59) | 41 (41) | 47 (47) | 40 (40) | 59 (60) | 77 (78) | 55 (56) | 32 (32) | 84 (85) | 76 (77) | 4 (4) | 95 (96) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (56) | 27 (48) | 36 (64) | 29 (51) | 30 (54) | 38 (68) | IR | 42 (75) | 30 (54) | 38 (68) | 25 (45) | 28 (50) | 31 (55) | 35 (63) | 24 (42) | 17 (31) | 23 (41) | 30 (54) | 39 (69) | 31 (55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 41 (74) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2015 (58) | 31 (54) | 32 (56) | 6 (11) | 24 (41) | 36 (62) | IR | 43 (74) | 41 (71) | 26 (44) | 27 (47) | 30 (52) | 24 (41) | 39 (68) | 15 (25) | 27 (46) | 15 (25) | 26 (45) | 38 (65) | 26 (44) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 41 (70) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (49) | 24 (48) | 20 (41) | 18 (37) | 21 (42) | 20 (41) | IR | 22 (45) | 21 (42) | 22 (44) | 15 (30) | 19 (39) | 30 (61) | 24 (48) | 13 (26) | 20 (40) | 15 (30) | 20 (41) | 22 (44) | 21 (42) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (48) | 5 (10) | 0 (0) | 17 (35) | |

| Escherichia coli | 2012 (180) | 50 (28) | 124 (69) | 0 (0) | 86 (48) | 4 (2) | 85 (47) | 153 (85) | 160 (89) | 0 (0) | 34 (19) | 166 (92) | 47 (26) | 118 (66) | 32 (18) | 149 (83) | 83 (46) | 40 (22) | 164 (91) | 76 (42) | 157 (87) | 171 (95) | 169 (94) | 9 (5) | 178 (99) | 0 (0) |

| 2013 (264) | 58 (22) | 219 (83) | 71 (27) | 121 (46) | 216 (82) | 153 (58) | 232 (88) | 230 (87) | 116 (44) | 116 (44) | 243 (92) | 69 (26) | 161 (61) | 48 (18) | 206 (78) | 121 (46) | 74 (28) | 246 (93) | 116 (44) | 214 (81) | 259 (98) | 253 (96) | 1 (0.3) | 264 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (248) | 62 (25) | 174 (70) | 62 (25) | 82 (33) | 208 (84) | 149 (60) | 193(78) | 82 (33) | 208 (84) | 42 (17) | 218 (88) | 117 (47) | 124 (50) | 42 (17) | 188 (76) | 64 (26) | 87 (35) | 181 (73) | 107 (43) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 181 (73) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2015 (172) | 53 (31) | 136 (79) | 52 (30) | 83 (48) | 151 (88) | 0 (0) | 146 (85) | 139 (81) | 96 (56) | 60 (35) | 151 (88) | 120 (70) | 86 (50) | 26 (15) | 146 (85) | 34 (20) | 50 (29) | 151 (88) | 101 (59) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 139 (81) | 7 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (216) | 69 (32) | 179 (83) | 71 (33) | 102 (47) | 192 (89) | 0 (0) | 179 (83) | 192 (89) | 117 (54) | 63 (29) | 197 (91) | 153 (71) | 104 (48) | 26 (12) | 188 (87) | 41 (19) | 63 (29) | 194 (90) | 106 (49) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 166 (77) | 89 (41) | 0 (0) | 147 (68) | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2012 (371) | 301 (81) | 341 (92) | 0 (0) | 308 (83) | 0 (0) | 289 (78) | 352 (95) | 349 (94) | 0 (0) | 193 (52) | 341 (92) | 223 (60) | 338 (91) | 237 (64) | 312 (84) | 286 (77) | 289 (78) | 356 (96) | 293 (79) | 249 (67) | IR | 371 (100) | 111 (30) | 371 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 2013 (290) | 206 (71) | 267 (92) | 168 (58) | 229(79) | 247 (85) | 238 (82) | 273 (94) | 273 (94) | 186 (64) | 186 (64) | 261 (90) | 171 (59) | 229 (79) | 165 (57) | 200 (69) | 215 (74) | 223 (77) | 273 (94) | 220 (76) | 136 (47) | IR | 281 (97) | 78 (27) | 290 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (206) | 122 (59) | 167 (81) | 136 (66) | 148 (72) | 187 (91) | 161 (78) | 173 (84) | 148 (72) | 187 (91) | 97 (47) | 183 (89) | 146 (71) | 157 (76) | 103 (50) | 150 (73) | 138 (67) | 161 (78) | 173 (84) | 150 (73) | 0 (0) | IR | 177 (86) | 29 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2015 (162) | 115 (71) | 149 (92) | 78 (48) | 125 (77) | 147 (91) | 0 (0) | 152 (94) | 152 (94) | 117 (72) | 91 (56) | 144 (89) | 118 (73) | 122 (75) | 73 (45) | 138 (85) | 84 (52) | 118 (73) | 156 (96) | 120 (74) | 0 (0) | IR | 152 (94) | 8 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (313) | 238 (76) | 269 (86) | 200 (64) | 257 (82) | 297 (95) | 0 (0) | 285 (91) | 285 (91) | 238 (76) | 160 (51) | 269 (86) | 247 (79) | 231 (74) | 135 (43) | 254 (81) | 182 (58) | 257 (82) | 297 (95) | 222 (71) | 0 (0) | IR | 282 (90) | 16 (5) | 0 (0) | 194 (62) | |

| Morganella spp. | 2012 (8) | 3 (33) | 4 (44) | 0 (0) | 6 (78) | 0 (0) | 6 (78) | 4 (56) | 4 (56) | 0 (0) | 3 (38) | 6 (78) | 0 (0) | 5(67) | 3(33) | 5 (67) | 4 (56) | 3 (33) | 5 (63) | 2 (25) | 6 (71) | 7 (88) | 6 (75) | IR | 6 (75) | 0 (0) |

| 2013 (13) | 5 (38) | 5 (40) | 4 (30) | 7 (56) | 0 (0) | 11 (88) | 8 (63) | 8 (64) | 4 (30) | 4 (30) | 11 (81) | 13 (100) | 7 (50) | 4 (31) | 10 (75) | 7 (50) | 6 (44) | 8 (63) | 4 (27) | 13 (100) | 11 (83) | 10 (75) | IR | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (18) | 10 (53) | 6 (35) | 1 (7) | 10 (53) | 12 (64) | 18 (100) | 13 (71) | 10 (53) | 12 (64) | 12 (67) | 14 (77) | 9 (50) | 13 (71) | 1 (7) | 13 (71) | 2 (12) | 12 (64) | 5 (29) | 4 (24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (53) | IR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2015 (5) | 1 (25) | 1 (13) | 1 (17) | 1 (14) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 1 (17) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (38) | 0 (0) | 2 (38) | 1 (25) | 2 (38) | 1 (13) | 2 (33) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | IR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (7) | 4 (50) | 5 (75) | 4 (50) | 5 (75) | 4 (50) | 0 (0) | 5 (75) | 5 (75) | 5 (75) | 2 (33) | 5 (75) | 0 (0) | 5 (75) | 4 (50) | 5 (75) | 2 (25) | 5 (75) | 5 (75) | 4 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (75) | IR | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | |

| Proteus spp. | 2012 (104) | 66 (63) | 62 (60) | 0 (0) | 22 (21) | 0 (0) | 27 (26) | 74 (71) | 76 (73) | 0 (0) | 70 (67) | 79 (76) | 26 (25) | 56 (54) | 17 (16) | 72 (69) | 49 (47) | 87 (84) | 35 (34) | 8 (8) | IR | 61 (59) | 56 (54) | IR | 104 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 2013 (106) | 42 (40) | 86(81) | 39 (37) | 37 (35) | 57 (54) | 27 (25) | 88 (83) | 76 (72) | 35 (33) | 35 (33) | 75 (71) | 0 (0) | 71 (67) | 18 (17) | 78 (74) | 41 (39) | 88 (83) | 29 (27) | 11 (10) | IR | 61 (58) | 34 (32) | IR | 106 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (46) | 20 (43) | 31 (68) | 15 (32) | 19 (41) | 21 (46) | 16 (35) | 38 (82) | 19 (41) | 21 (46) | 23 (51) | 34 (73) | 0 (0) | 35 (75) | 13 (29) | 29 (62) | 14 (30) | 38 (82) | 10 (21) | 3 (7) | IR | 0 (0) | 15 (33) | IR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2015 (36) | 16 (45) | 26 (71) | 2 (6) | 1 (4) | 24 (67) | 0 (0) | 25 (70) | 26 (72) | 0 (0) | 26 (71) | 31 (86) | 0 (0) | 23 (64) | 0 (0) | 26 (72) | 0 (0) | 31 (86) | 4 (11) | 4 (11) | IR | 0 (0) | 7 (20) | IR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (41) | 22 (54) | 25 (60) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 23 (55) | 0 (0) | 29 (71) | 27 (67) | 2 (6) | 29 (71) | 18 (44) | 0 (0) | 28 (69) | 7 (18) | 29 (71) | 1 (3) | 29 (71) | 9 (23) | 1 (3) | IR | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | IR | 0 (0) | 30 (73) | |

| Providencia spp. | 2012 (42) | 31 (73) | 27 (64) | 0 (0) | 28 (67) | 0 (0) | 22 (53) | 31 (73) | 34 (80) | 0 (0) | 15 (36) | 38 (90) | 0 (0) | 37 (87) | 8 (18) | 34 (82) | 26 (63) | 35 (84) | 29 (68) | 6 (15) | IR | 32 (77) | 32 (75) | IR | 42 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 2013 (39) | 26 (67) | 26 (66) | 28 (73) | 31 (79) | 35 (90) | 31 (79) | 35 (91) | 36 (93) | 23 (59) | 23 (59) | 32 (81) | 9 (22) | 32 (81) | 18 (47) | 33(84) | 29 (75) | 31 (79) | 27 (70) | 24 (61) | IR | 39 (100) | 32 (83) | IR | 39 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (22) | 17 (77) | 14 (62) | 11 (50) | 17 (77) | 20 (89) | 20 (89) | 17 (77) | 17 (77) | 20 (89) | 15 (67) | 18 (83) | 0 (0) | 17 (77) | 10 (44) | 12 (54) | 12 (54) | 17 (78) | 17 (77) | 17 (77) | IR | 0 (0) | 15 (70) | IR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2015 (1) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | IR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | IR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (5) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (80) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (80) | 0 (0) | 4 (80) | 2 (40) | 4 (80) | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | IR | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | IR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Salmonella spp. | 2012 (0) | 0 (43) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (13) | 0 (6) | 0 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (8) | 0 (21) | 0 (50) | 0 (25) | 0 (7) | 0 (7) | 0 (7) | 0 (20) | 0 (27) | 0 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (21) | 0 (38) | 0 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2013 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 3 (83) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2014 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 0 (0) | 0 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2015 (1) | 0 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (40) | 0 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (60) | 0 (0) | 1 (60) | 0 (0) | 0 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (40) | 0 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (2) | 0 (15) | 0 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (8) | 0 (15) | 0 (0) | 1 (46) | 0 (0) | 0 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Serratia spp. | 2012 (54) | 49 (91) | 44 (82) | 0 (0) | 46 (86) | 0 (0) | IR | 40 (74) | 51 (94) | 0 (0) | 14 (26) | 46 (85) | 0 (0) | 21 (38) | 8 (15) | 26 (49) | 12 (23) | 46 (85) | 39 (73) | 8 (15) | 15 (27) | 32 (59) | 42 (78) | 0 (0) | 52 (97) | 0 (0) |

| 2013 (56) | 18 (32) | 31 (55) | 13 (23) | 21 (37) | 44 (79) | IR | 42 (75) | 38 (68) | 21 (38) | 21 (38) | 18 (32) | 22 (40) | 12 (21) | 14 (25) | 17 (30) | 20 (35) | 29 (51) | 41 (74) | 7 (13) | 18 (33) | 31 (56) | 39 (70) | 0 (0) | 46 (83) | 56 (100) | |

| 2014 (35) | 14 (41) | 17 (48) | 2 (5) | 7 (21) | 16 (47) | IR | 18 (50) | 7 (21) | 16 (47) | 8 (24) | 14 (41) | 12 (33) | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 9 (25) | 4 (10) | 18 (50) | 14 (40) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (45) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2015 (9) | 1 (11) | 4 (44) | 0 (0) | 2 (25) | 3 (33) | IR | 4 (44) | 0 (0) | 3 (38) | 4 (43) | 4 (44) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | 5 (50) | 8 (88) | 5 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (42) | 23 (54) | 28 (67) | 7 (17) | 14 (33) | 32 (77) | IR | 28 (67) | 28 (67) | 21 (50) | 16 (38) | 24 (57) | 0 (0) | 11 (27) | 1 (3) | 24 (58) | 0 (0) | 28 (67) | 25 (60) | 13 (31) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 (60) | 10 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: AMK, amikacin; CEFEP, cefepime; CEFEPTAZ, cefepime-tazobactam; CEFOSUL, cefoperazone-sulbactam; CEFOT, cefotaxime; CEFOX, cefoxitin; CEFTAZ, ceftazidime; CEFTRX, ceftriaxone; CEFTRXSUL, ceftriaxone-sulbactam; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIPRO, ciprofloxacin; ERTA, ertapenem; GENTA, gentamicin; IMI, imipenem; IR, intrinsic resistance; LEVO, levofloxacin; MERO, meropenem; NETIL, netilmicin; PIP, piperacillin; PIPTAZ, piperacillin-tazobactam; TETRA, tetracycline; TIC, ticarcillin-clavulanate; TIG, tigecycline; TOBRA, tobramycin; TMZ, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Note: N denotes the number of isolates.

In OPD, E. coli showed less than 70% resistance to cephalosporins, resistance against ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin was 79.4 and 69%, respectively. Among aminoglycosides, maximum resistance was seen against gentamycin (44%), followed by tobramycin (31.5%) and amikacin (18.3%). Among carbapenems, maximum resistance was observed against ertapenem (24.5%), followed by meropenem (18.9%) and imipenem (5.3%). E. coli showed 17% resistance to chloramphenicol. Klebsiella spp. showed 77% resistance to ceftazidime, 70.5% resistance to cefepime, and 65% resistance to levofloxacin. Among carbapenems, maximum resistance was observed against meropenem (59%), followed by imipenem (46.3%) and ertapenem (34%). Among aminoglycosides, maximum resistance seen in Klebsiella spp. isolates was against gentamycin (70%), followed by tobramycin (62.6%) and amikacin (64%). ►Table 4 shows the year-wise resistance pattern against different antibiotics of Enterobacteriaceae of OPD patients. We observed least resistance against tigecycline among both E. coli and Klebsiella spp. (1.5 and 12.6%, respectively).

| Organism name | Year | AMK, N (%) | CEFEP, N (%) | CEFEPTAZ, N (%) | CEFOSUL, N (%) | CEFOT, N (%) | CEFOX, N (%) | CEFTAZ, N (%) | CEFTRX, N (%) | CEFTRXSUL, N (%) | CHL, N (%) | CIPRO, N (%) | ERTA, N (%) | GENTA, N (%) | IMI, N (%) | LEVO, N (%) | MERO, N (%) | NETIL, N (%) | PIP, N (%) | PIPTAZ, N (%) | TETRA, N (%) | TIC, N (%) | TICLAV, N (%) | TIG, N (%) | TOBRA, N (%) | TMZ, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrobacter spp. | 2012 (5) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | NA | 2 (40) | NA | 2 (100) | 3 (60) | 3 (75) | NA | 2 (40) | 1 (25) | 1 (100) | NA | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 2 (0) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 3 (60) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (2) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | NA | 1 (50) | NA | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | NA | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 3 (60) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA | |

| 2014 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (100) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 1 (16.7) | |

| 2015 (3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (33.3) | |

| 2016 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (66.) | NA | NA | 2 (66.) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (100) | 1 (33.) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | |

| Enterobacter spp. | 2012 (11) | 5 (50) | 6 (54.6) | NA | 6 (60) | NA | IR | 6 (60) | 7 (63.6) | NA | 4 (44.) | 6 (54.6) | 1 (100) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (57.1) | 4 (50) | 4 (50) | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 3 (50) | 2 (25) | 6 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (31) | 6 (19.4) | 5 (16.1) | 4 (16) | 4 (13.3) | 4 (30.8) | IR | 15 (48.4) | 4 (12.9) | 5 (20) | 3 (10.) | 4 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.9) | 2 (7.1) | 11 (35.5) | 4 (13.8) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (14.3) | 11 (35.5) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (100) | NA | |

| 2014 (10) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (60) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (83.3) | IR | 6 (60) | 7 (70) | 4 (40) | 2 (25) | 5 (50) | 1 (50) | 6 (60) | 2 (20) | 3 (30) | 2 (20) | 3 (60) | 6 (60) | 3 (30) | NA | NA | 7 (70) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 7 (70) | |

| 2015 (10) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | 2 (20) | 3 (30) | 6 (66.7) | IR | 7 (70) | 5 (71.4) | 3 (30) | 2 (22.) | 5 (50) | 2 (66.) | 6 (60) | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | 1 (10) | 4 (40) | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | NA | NA | 8 (80) | 0 (0) | NA | 6 (66.7) | |

| 2016 (15) | 8 (53.3) | 6 (40) | 4 (26.7) | 5 (33.3) | 1 (50) | IR | 5 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | 6 (40) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (20) | 4 (57.1) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (20) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (20) | 6 (40) | 6 (40) | 5 (33.3) | NA | NA | 6 (42.9) | 1 (7.1) | NA | 3 (37.5) | |

| Escherichia coli | 2012 (77) | 15 (19.5) | 36 (61) | NA | 31 (41.9) | 3 (100) | 33 (50.8) | 57 (79.2) | 62 (81.6) | NA | 18 (23.3) | 61 (82.4) | 6 (15.8) | 42 (55) | 6 (8) | 58 (77.3) | 27 (35) | 10 (16.7) | 49 (80.3) | 13 (28.3) | 54 (80.6) | 60 (89.6) | 72 (93) | 1 (2) | 50 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (113) | 16 (14.2) | 68 (72.3) | 8 (11.8) | 42 (37.5) | 21 (63.6) | 48 (45.7) | 87 (77) | 82 (72.6) | 18 (26.9) | 5 (10.4) | 94 (83.2) | 12 (16) | 62 (54.9) | 7 (6.2) | 77 (68.8) | 27 (24) | 20 (18) | 97 (85.8) | 37 (33) | 39 (84.8) | 48 (96) | 99 (88) | 1 (1) | 25 (100) | NA | |

| 2014 (83) | 7 (8.4) | 44 (53.7) | 7 (9.2) | 29 (35) | 32 (62.8) | 24 (43.6) | 48 (60.8) | 50 (63.3) | 11 (13.4) | 2 (7.1) | 59 (74.7) | 15 (33.3) | 31 (37.8) | 4 (4.9) | 45 (54.9) | 11 (13.8) | 13 (20) | 43 (52.4) | 16 (19.5) | NA | NA | 53 (64) | 1 (0.9) | 75 (100) | 52 (65) | |

| 2015 (70) | 15 (21.4) | 51 (75) | 17 (28.8) | 22 (34.9) | 46 (79.3) | NA | 41 (58) | 28 (65.1) | 28 (41.8) | 5 (7) | 57 (81.4) | 23 (48.9) | 26 (37) | 3(4) | 52 (77.6) | 9 (12.9) | 16 (27.6) | 52 (75.4) | 26 (37.1) | NA | NA | 39 (56) | 0 (0) | NA | 47 (69.1) | |

| 2016 (133) | 34 (26) | 86 (67.7) | 28 (21.7) | 45 (34) | 47 (88.7) | NA | 67 (50) | 103 (82.4) | 53 (41.7) | 8(6) | 107 (82.3) | 61 (70.9) | 47 (35) | 5 (3.8) | 96 (75.6) | 16 (12) | 30 (23.3) | 112 (87.5) | 46 (35.9) | NA | NA | 69 (52) | 0 (0) | NA | 65 (60.8) | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2012 (47) | 40 (87) | 42 (89.3) | NA | 39 (83) | NA | 40 (93) | 42 (89.1) | 40 (88.9) | NA | 26 (72.2) | 42 (91.3) | 14 (70) | 42 (91.3) | 33 (69.6) | 42 (89) | 33 (75) | 32 (88.9) | 35 (97.2) | 20 (80) | 21 (56.8) | IR | 31 (96.9) | 7 (26.9) | 42 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (33) | 14 (42.4) | 24 (72.7) | 5 (23.8) | 13 (41.9) | 2 (16.7) | 18 (56.3) | 26 (79) | 18 (54.6) | 6 (28.6) | 8 (32) | 18 (56.3) | 9 (39.1) | 12 (37.5) | 15 (46) | 25 (76) | 16 (51.6) | 14 (42.4) | 26 (78.8) | 13 (40.6) | 3 (30) | IR | 27 (81.8) | 6 (21.4) | 10 (100) | NA | |

| 2014 (26) | 13 (50) | 18 (69.2) | 11 (45.8) | 12 (48) | 11 (61.1) | 11 (55) | 20 (76) | 16 (61.5) | 13 (50) | 6 (46.2) | 12 (46.2) | 5 (33.3) | 14 (53.9) | 11 (42) | 16 (61.6) | 12 (46.2) | 11 (55) | 15 (57.7) | 14 (53.9) | NA | IR | 17 (65.4) | 4 (18.2) | 52 (100) | 13 (54.2) | |

| 2015 (13) | 7 (53.9) | 8 (61.52) | 5 (50) | 7 (53.9) | 7 (77.8) | NA | 9 (67) | 4 (66.7) | 8 (61.5) | 4 (57.1) | 9 (69.2) | 4 (44.4) | 9 (69.2) | 4(30.8) | 6 (46.1) | 5 (38.5) | 6 (60) | 11 (84.6) | 8 (66.7) | NA | IR | 9 (75) | 1 (8.3) | NA | 6 (50) | |

| 2016 (47) | 32 (71.1) | 25 (53.2) | 29 (61.7) | 35 (74.5) | 24 (88.9) | NA | 31 (65.4) | 38 (82.6) | 36 (76.6) | 25 (69.4) | 39 (83) | 25 (80.7) | 39 (83) | 14 (30) | 19 (40) | 32 (68.1) | 37 (78.7) | 41 (87.2) | 31 (72.1) | NA | IR | 42 (91.3) | 3 (7) | NA | 26 (63.4) | |

| Morganella spp. | 2012 (4) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | NA | 3 (75) | NA | 3 (100) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | NA | 1 (33.3) | 2 (50) | NA | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (75) | 2 (66.7) | IR | 1 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | NA | 3 (100) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 3 (100) | NA | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 2 (66.7) | IR | 1 (100) | NA | |

| 2014 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 1 (100) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | 2 (40) | IR | NA | 2 (50) | |

| 2015 (3) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | NA | 2 (66.7) | 1 (50) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (66.7) | NA | 3 (100) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (100) | 2 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) | NA | NA | 2 (66.7) | IR | NA | 3 (100) | |

| 2016 (3) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (100) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (100) | 1 (100) | NA | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 1 (50) | 3 (100) | NA | 3 (100) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (100) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 2 (66.7) | NA | NA | 3 (100) | IR | NA | 1 (100) | |

| Proteus spp. | 2012 (22) | 10 (45.5) | 7 (36.8) | NA | 3 (13.6) | NA | 6 (31.6) | 13 (59.1) | 13 (61.9) | NA | 12 (66.7) | NA | 0 (0) | 8 (36.4) | 3 (13.6) | 11 (50) | 6 (28.6) | 11 (61.1) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (12.5) | IR | 6 (46.2) | 11 (61.1) | IR | 12 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (20) | 4 (20) | 6 (50) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 3 (50) | 3 (15) | 13 (65) | 11 (55) | 0 (0) | 10 (52.6) | NA | NA | 9 (45) | 0 (0) | 12 (60) | 5 (26.3) | 14 (70) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (5.6) | IR | 5 (83.3) | 9 (52.9) | IR | 12 (100) | NA | |

| 2014 (11) | 3 (27.3) | 5 (45.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 5 (45.5) | 1 (10) | 7 (63.6) | 7 (63.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (28.6) | 6 (54.55) | 0 (0) | 5 (45.5) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) | 7 (63.6) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | IR | NA | 2 (18.2) | IR | 24 (100) | 8 (80) | |

| 2015 (11) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (50) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (57.1) | NA | 6 (54.6) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 6 (66.7) | 4 (54.55) | NA | 6 (54.6) | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | IR | NA | 1 (10) | IR | NA | 7 (63.6) | |

| 2016 (9) | 7 (77.8) | 5 (55.6) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (22.2) | 4 (66.7) | NA | 7 (77.8) | 5 (71.4) | 1 (11.1) | 7 (87.5) | 5 (50) | NA | 6 (85.7) | 3 (42.9) | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (77.8) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (12.5) | IR | NA | 1 (11.1) | IR | NA | 5 (83.3) | |

| Providencia spp. | 2012 (3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (100) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | 2 (66.7) | NA | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | IR | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50) | IR | 1 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (5) | 3 (60) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 4 (80) | 4 (80) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (80) | (0) | 4 (80) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | 4 (80) | 3 (60) | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | IR | 3 (100) | 3 (60) | IR | 3 (100) | NA | |

| 2014 (2) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | NA | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | IR | NA | 1 (50) | IR | 4 (100) | 1 (50) | |

| 2015 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | NA | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (100) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | IR | NA | 0 (0) | IR | NA | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 2 (100) | NA | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | NA | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | IR | NA | 0 (0) | IR | NA | 0 (0) | |

| Salmonella spp. | 2012 (16) | 6 (42.9) | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (8.3) | NA | 2 (18.2) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | NA | 1 (0) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (50) | 3 (25) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (20) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 3 (21.4) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (7.7) | NA | NA |

| 2013 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | |

| 2014 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (20) | |

| 2015 (4) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 2 (50) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | NA | 3 (75) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | NA | NA | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | |

| 2016 (11) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 2 (18.2) | NA | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | NA | 2 (20) | |

| Serratia spp. | 2012 (2) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | NA | 1 (50) | NA | IR | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | NA | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | NA | 1 (100) | NA | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA |

| 2013 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | IR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA | |

| 2014 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | IR | 0 (0) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.3) | NA | NA | NA | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | |

| 2015 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | NA | NA | NA | IR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2016 (1) | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | IR | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | NA | NA | NA | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: AMK, amikacin; CEFEP, cefepime; CEFEPTAZ, cefepime-tazobactam; CEFOSUL, cefoperazone-sulbactam; CEFOT, cefotaxime; CEFOX, cefoxitin; CEFTAZ, ceftazidime; CEFTRX, ceftriaxone; CEFTRXSUL, ceftriaxone-sulbactam; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIPRO, ciprofloxacin; ERTA, ertapenem; GENTA, gentamicin; IMI, imipenem; IR, intrinsic resistance; LEVO, levofloxacin; MERO, meropenem; NA, not applicable; NETIL, netilmicin; PIP, piperacillin; PIPTAZ, piperacillin-tazobactam; TETRA, tetracycline; TIC, ticarcillin-clavulanate; TIG, tigecycline; OPD, outpatient department; TOBRA, tobramycin; TMZ, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Note: N denotes the number of isolates.

From 5-years resistance pattern in ICUs, we observed that E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates showed some decrease in resistance percentage against some antimicrobials. About 32% decreased resistance was observed in E. coli against meropenem, while against Klebsiella spp. isolates it was 34%. Against piperacillin-tazobactam, E. coli showed 25% decreased resistance, while Klebsiella spp. showed 22%. Both E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates showed 22% decreased resistance against cefoperazone-sulbactam. In addition to these, Klebsiella spp. isolates also showed decreased resistance against ceftriaxone (7%), 21% against ciprofloxacin, 12% against ticarcillin-clavulanate, 17% against gentamycin, 3% decreased resistance against imipenem, and 26% against levofloxacin.

In wards also, both E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates showed decreased resistance across the study period. In E. coli, maximum decreased resistance was observed against meropenem (27%), followed by gentamicin (18%) and imipenem (6%). In Klebsiella spp. maximum decreased resistance was observed against tigecycline (25%), followed by imipenem (21%), meropenem (19%), gentamicin (17%), piperacillin-tazobactam (8%), and ciprofloxacin (6%).

In OPD patients, E. coli showed maximum decreased resistance against ticarcillin-clavulanate (41%), followed by ceftazidime (29%), meropenem (23%), gentamycin (20%), chloramphenicol (17.7%), cefoperazone-sulbactam (8%), imipenem (4.2%), and tigecycline (1%). Klebsiella spp. isolates showed maximum decreased resistance against levofloxacin (49%), followed by imipenem (39.6%), cefepime (36.1%), and ceftazidime (23.7%).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the antimicrobial resistance pattern of Enterobacteriaceae in trauma patients. We found that in ICUs and wards, the most common gram-negative pathogens responsible for nosocomial infections were Klebsiella spp., followed by E. coli and Enterobacter spp. These findings are in concordant with other published studies.[14,15] In OPD patients, the most common gram-negative pathogens responsible for nosocomial infections were E. coli, followed by Klebsiella spp. and Enterobacter spp.

Our study showed Enterobacteriaceae isolates from ICUs, wards, and OPD showed high level of resistant to all classes of cephalosporins. In addition, β lactam and β-lactamase inhibitor combination remained less effective. This encouraged therapy with quinolones, aminoglycosides, or carbapenems. However, among quinolones, aminoglycosides, and carbapenems we found least resistance to carbapenems followed by aminoglycosides and quinolones in all settings; this result is in concordant with another study.[16] This shows that the resistance is increasing to currently used antibiotics, and the older drugs may prove as an effective option. Both imipenem and meropenem showed good activity against Enterobacteriaceae even when they are producing either ESBLs or Amp C. It was found that meropenem showed ≥ 97.3% sensitivity among Enterobacteriaceae isolates while imipenem showed 87.5% sensitivity, showing that meropenem is 4 to 16 times more active than imipenem against Enterobacteriaceae.[17,18] In contrast, we found imipenem more effective than meropenem in all settings. Among aminoglycosides group of antimicrobial agents, less resistance was shown against amikacin than gentamycin; similar results were observed in other published studies.[19,20] The least resistant was observed against tigecycline (1–15%) among all isolates in all settings. A similar result was found in another study where tigecycline was active against multidrug-resistant E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates.[21,22]

From 5-year resistance pattern of antimicrobials (►Tables 2-4), we found that Enterobacteriaceae isolates showed increased sensitivity against some antimicrobials in all settings. In ICU settings, both E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates showed significant increased sensitivity percentage against β-lactamase inhibitors and carbapenem. Klebsiella spp. isolates also showed increased sensitivity against quinolones and aminoglycosides (gentamycin). These results suggest the substantial use of these antibiotics against these pathogens. In wards and OPDs, increased sensitivity was observed across the study period; both pathogens showed increased sensitivity against carbapenems (meropenem, imipenem) and aminoglycosides (gentamycin). Klebsiella spp. isolates also showed increased sensitivity against piperacillin-tazobactam, ciprofloxacin, and tigecycline in wards settings. In OPD patients, increased sensitivity against ceftazidime and cefepime was also observed in both pathogens, showing primitive antibiotics like ceftazidime and cefepime can be used as choice of antibiotic against these pathogens in OPD patients, although it is administered intravenously.

Among different classes of antimicrobials, tigecycline proved most effective in all settings. Tigecycline is a potent therapeutic option for multidrug resistance enterobacterial infections. Although tigecycline resistance has been observed, it is still active among Enterobacteriaceae. However, increased resistance was observed than other studies which is < 10%.[23-26]

This study is among the very few studies done in the Indian setting. The large sample size of this study makes its results more reliable. Isolates of Enterobacteriaceae included in this study were collected from multiple sources in terms of location of the patients and types of samples. Therefore, the findings can be generalized to a variety of location of patients and samples. However, all the samples were collected from the apex trauma center of a tertiary care center. This limits the generalizability of the study in terms of study settings. The burden, profile, and AST of Enterobacteriaceae bacteria isolated from a secondary or primary care setting or from community settings are expected to be different from this study. Hence the interpretation with reference to study setting should be cautiously done.

No intermediate isolate was reported in the study results. This study includes the results based on automated system (Vitek2 compact system). These need to be validated by molecular methods or by sequencing.

Conclusion

Emergences of multiple drug resistance among bacteria are occurring at an alarming rate worldwide. This crisis is due to the inappropriate and overuse of existing antibiotics and lack of development of new antibiotics.[27,28] Tigecycline proved to be an effective agent against Enterobacteriaceae. Use of tigecycline needs to be strictly monitored to prevent development and dissemination of resistance against it. In addition to curtailing the antibiotic misuse and abuse, it becomes even more important to avoid the emergence of antibiotic resistance by taking measures like strict implementation of infection control guidelines, proper hand hygiene, and antimicrobial stewardship programs that include optimal selection, dose, and duration of treatment.

Ethical Approval

Since this is a retrospective study and the data obtained was from routine laboratory work, this study was exempted from the attainment of ethical approval.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and implementation of the study. All authors contributed to analyzing the data, writing and reviewing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

- Bacteriophage therapy: a potential solution for the antibiotic resistance crisis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8(02):129-136.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of infectious disease antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. 2013 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013. Accessed July 4, 2020

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic resistance: a public health crisis. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(04):314-316.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Update on the antibiotic resistance crisis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;18:56-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of antibiotic resistance on clinical outcomes and the cost of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(Suppl. 04):N114-N120.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(04):657-686.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(04):657-686.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- et al Roles of beta-lactamases and porins in activities of carbapenems and cephalosporins against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(07):1669-1673.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- et al Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(09):597-602.

- [Google Scholar]

- et al Antimicrobial resistance in Enterobacteriaceae from healthy broilers in Egypt: emergence of colistin-resistant and extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Gut Pathog. 2018;10:39.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- et al First report on a cluster of colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from a tertiary care center in India: whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Genome Announc. 2017;5(05):e01466-e16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- et al Multiple mutations in lipid-A modification pathway & novel fosA variants in colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Future Sci OA. 2018;4(07):FSO319.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. In: CLSI supplement M100 In: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (28th). 2018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(19):1804-1813.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- et al Treatment of health-care-associated infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria: a consensus statement. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(02):133-139.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Variations in the occurrence of resistance phenotypes and carbapenemase genes among Enterobacteriaceae isolates in 20 years of the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(Suppl. 01):S23-S33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meropenem activity against European isolates: report on the MYSTIC (Meropenem Yearly Susceptibility Test Information Collection) 2006 results. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;60(02):185-192.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Carbapenem Discussion Group. Imipenem and meropenem: comparison of in vitro activity, pharmacokinetics, clinical trials and adverse effects. Can J Infect Dis. 1998;9(04):215-228.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Controlled comparison of amikacin and gentamicin. N Engl J Med. 1977;296(07):349-353.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The antimicrobial activity of amikacin in comparison with three other aminoglycoside-antibiotics (author's transl) Med Klin. 1978;73(24):914-917.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosocomial blood-stream infections from extended- spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumonia from GB Pant Hospital, New Delhi. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4(08):517-520.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigecycline activity tested against antimicrobial resistant surveillance subsets of clinical bacteria collected worldwide (2011) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76(02):217-221.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susceptibility of important gram-negative pathogens to tigecycline and other antibiotics in Latin America between 2004 and 2010. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2012;11:29.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- et al Nationwide surveillance in Taiwan of the in-vitro activity of tigecycline against clinical isolates of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32(Suppl. 03):S179-S183.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigecycline in vitro activity against commonly encountered multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens in a Middle Eastern country. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62(04):411-415.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigecycline susceptibility report from an Indian tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129(04):446-450.

- [Google Scholar]

- The multifaceted roles of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:47.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seven ways to preserve the miracle of antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(10):1445-1450.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]