Translate this page into:

Clinical Patterns and Hematological Spectrum in Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

Address for correspondence: Dr. Vanamala Alwar, E-mail: vanalwar@yahoo.com

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) results from red cell destruction due to circulating autoantibodies against red cell membrane antigens. They are classified etiologically into primary and secondary AIHAs. A positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT) is the hallmark of diagnosis for AIHA.

Methods and Results:

One hundred and seventy-five AIHA cases diagnosed based on positive DAT were included in the study. The cases showed a female predilection (M: F = 1:2.2) and a peak incidence in the third decade. Forty cases were found to be due to primary AIHA, while a majority (n = 135) had AIHA secondary to other causes. The primary AIHA cases had severe anemia at presentation (65%) and more often showed a blood picture indicative of hemolysis (48%). Forty-five percent of primary AIHAs showed positivity for both DAT and indirect antiglobulin test (IAT). Connective tissue disorders were the most common associated etiology in secondary AIH A0 (n = 63).

Conclusion:

AIHAs have a female predilection and commonly present with symptoms of anemia. AIHA secondary to other diseases (especially connective tissue disorders) is more common. Primary AIHAs presented with severe anemia and laboratory evidence of marked hemolysis.

Keywords

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

antiglobulin test

primary

secondary

INTRODUCTION

Immune hemolytic anemia can be either isoimmune or autoimmune in nature. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is an immune disorder caused by circulating antibodies against antigens on the red cell (RBCs) membrane resulting in shortened RBC life span.[1] Etiologically they are classified as primary (Idiopathic) and secondary (Co existing with another disease or drug induced). The antibodies sensitizing the RBCs are also varied. The most common form of AIHA is characterized by the presence of “warm” type of autoantibodies, which are IgG type and react optimally at 37°C, causing RBC destruction extravascularly by tissue macrophages. The other two antibodies include “cold” agglutinins (IgM type) and Donath Landsteiner antibodies (IgG type).[2] The cornerstone of diagnosis of AIHA is a positive Antihuman globulin or Coombs test, in the presence of hemolysis.[1] Clinically, these patients present with variable features usually including a sudden onset of pallor, mild jaundice, and splenomegaly on examination.[2] Though the rate of hemolysis and hence the clinical manifestation depend mainly on the type of antibodies and their capacity to fix complements, etiology and demographics also play a role.[1] With this background, we analyzed the clinical features, hematological and serological parameters in AIHAs for a 18 month period in a tertiary hospital setup to observe any patterns of presentation, which may give direction to diagnosis and prognosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The patients who were screened in the study were referred to our blood bank for evaluation of a possible autoimmune cause of anemia over a period of 18 months, including a retrospective analysis from January to December 2003 and prospective analysis from January to June 2005. The tests performed included direct and indirect antiglobulin test (DAT, IAT) and cold agglutinin titer (CAT). Any patient who was found to be antiglobulin test positive was included in the study. The gel card technique using Diamed id cards with polyspecific antihuman globulin was used for DAT and IAT.

During the screening process, the details pertaining to demographics and disease status including, the presenting complaints, clinical features at the time of presentation were retrieved from the archives. DAT positive cases due to Rh and ABO incompatibility in neonates and IAT-positive cases in Rh-negative pregnant women were excluded. Patients with history of pregnancy or those who received blood transfusion in the previous 3 months were also excluded.

The laboratory parameters were then correlated including hemoglobin, total and differential leukocyte counts, reticulocyte count, and peripheral smear findings. The database was compiled in excel sheet and analyzed. Since this was an observational study, only percentage calculations have been employed. The institution's ethical committee had approved this study.

RESULTS

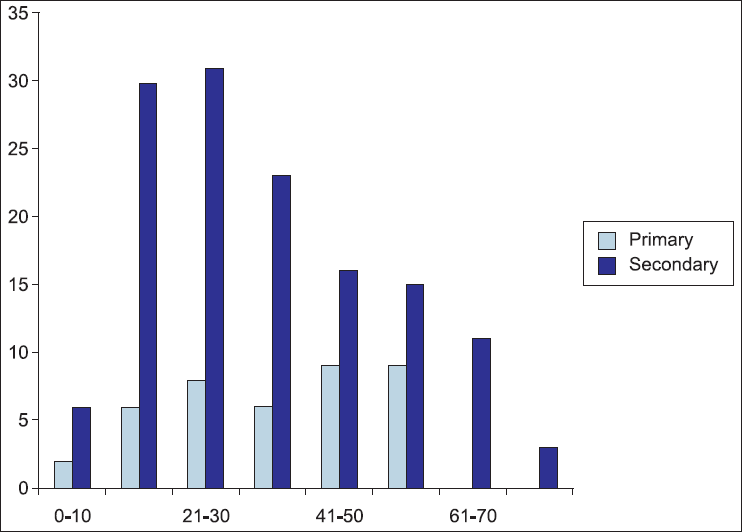

A total of 175 cases were evaluated. The age of included patients at presentation ranged from 6 to 84 years, with a peak incidence between 21 to 30 years and there was a female predilection (M : F = 1:2.2) [Figure 1].

- Age distribution of autoimmune hemolytic anemia cases

Etiologically, 40 patients had primary autoimmune hemolytic anemia, while in 135 cases the occurrence of AIHA was secondary to varied causes [Table 1]. The most common cause associated was connective tissue disorders (mainly systemic lupus erythematosis) in 63 cases.

| Primary | 40 |

| Secondary | 135 |

| Connective tissue diseases | 63 |

| HIV | 8 |

| Tuberculosis | 4 |

| End organ failure (renal) | 19 |

| Hematological malignancy | 14 |

| Other anemias | 12 |

| Miscellaneous | 15 |

Miscellaneous causes include drug induced, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, malaria etc.

The commonest presentation (36%) in our patients were symptoms attributed to the anemia like fatigue and breathlessness. The secondary AIHA cases commonly presented with systemic symptoms like fever, joint pains, and bleeding [Table 2].

| Presenting complaints | Primary | Secondary |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 26 | 37 |

| Fever | 8 | 51 |

| Joint pain | 0 | 22 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 8 |

| Bleeding | 4 | 11 |

| Infection | 0 | 6 |

| Examination findings | ||

| Hepatomegaly | 19 | 36 |

| Splenomegaly | 18 | 28 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 1 | 12 |

| No organomegaly | 2 | 59 |

On examination, Pallor (seen in 98% cases) was a universal finding. Hepatosplenomegaly was more often seen in primary AIHA [Table 2].

Laboratory findings

To analyze the correlation between etiology and severity of presentation, anemia was graded as severe anemia (Hb <5 g%), moderate anemia (Hb 6-10 gm%), and mild (Hb >10 but <12 g%). It was observed that severe anemia was seen in 26 cases (65%) of primary AIHA and 41 of secondary AIHA cases (30%) [Table 3].

| Hemoglobin | Primary | Secondary |

|---|---|---|

| 0-5 g% (Severe) | 26 | 41 |

| 5-10 g% (Moderate) | 10 | 80 |

| 10-12 g% (Mild) | 4 | 11 |

| >12 g% | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 40 | 135 |

Reticulocytosis was seen in 68% of primary and 20% of secondary AIHA. The morphological features on peripheral smear examination that suggest AIHA include clumping of RBCs, presence of many nucleated RBCs, and polychromasia. These classical features of AIHA were seen more often in primary (48%) than secondary AIHA (28%). Thrombocytopenia (<1 Χ 105/µl) was a frequent feature (n = 59) and was seen more often in secondary compared to primary AIHA (36% and 25%, respectively). 12 cases presented as pancytopenia.

Serologically, 45% of primary AIHA cases showed positivity for both DAT and IAT, indicative of high titers of circulating autoantibodies. Cold agglutinin titer was significantly raised in two cases [Table 4].

| Antiglobulin tests | Primary | Secondary |

|---|---|---|

| DAT | 20 | 115 |

| DAT+IAT | 18 | 20 |

| DAT + CAT | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 40 | 135 |

DISCUSSION

Accurate diagnosis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia is mandatory, as the condition requires different strategies for therapy and monitoring. Therefore, awareness of demographics, clinical presentation, and laboratory tests is required in the diagnosis of AIHAs. The present study includes a detailed clinico-hematological profile in a large series of 175 patients diagnosed as AIHA based on antiglobulin test positivity in a south Indian demography.

Few comprehensive studies have been undertaken across the Indian population. Choudhry et al, studied 21 cases, the most common feature at presentation in their study was pallor (89%), followed by jaundice (43%) and fever (38%). Splenomegaly and Hepatomegaly was seen in 81% and 76% cases, respectively. 15 cases were primary in etiology and 6 were secondary. 19 cases showed DAT positivity, while 7 were IAT positive.[3] Though fewer cases were studied, their findings are parallel to our study.

Genty et al, in their series studied 83 cases. They found 51% of the warm antibody cases were secondary to other causes, of which the most common were non-hodgkins lymphoma and connective tissue disorders (14 cases each). They stated in their conclusion that AIHA may precede the onset of lymphomas, therefore requiring further investigations and follow up.[4] Though in our series, secondary AIHA was seen to be more prevalent (77%), hematological malignancies were a rare secondary cause (n = 14) of which only two were lymphoid in origin.

Though the granulocytes and platelets are usually maintained in AIHA patients, the combination of AIHA with thrombocytopenia concurrently or sequentially (Evans syndrome) may occur as seen in our series (n = 59). Although the AIHAs are classically classified as primary and secondary, some investigators (Serrano et al.) have further expanded the classification and divided AIHA into four groups: Idiopathic; Secondary; Associated; Accompanying. The need and implications of such a classification have to be further evaluated. In their study they evaluated 200 cases. A high percentage of cases were related with severe underlying disease. Warm AIHA was seen in 74.5% and cold reacting in 19% cases.[5] In our study, cold reacting antibodies was rarely seen (1%). 99% were classified as warm AIHA.

While a positive DAT is the hallmark of diagnosis of AIHA, it is said that for DAT to be positive the number of IgG molecules sensitizing each RBCs must be usually above 200 molecules.[2,6] Various other studies give the threshold of IgG molecules to be detected by antiglobulin test to be anywhere from 100 to 500.[7,8] In the above context, AIHA with low titers of antibodies may present with negative DAT i.e. DAT negative AIHAs. False negative cases for DAT are recorded in 2-4% cases.[1] These patients usually have strong clinical evidence of hemolytic anemia, but the autoantibodies are not detected either in the eluate or serum. Several reasons have been postulated to explain the negative reaction:

The antibodies with low binding affinity may dissociate from the red cells during saline washing. Washing with low ionic strength saline or saline at 37 degrees C may help retain the antibodies on the cells.

The number of antibodies may be too few as explained above, to be detected by routine methods. In these cases, they may be demonstrated by flow cytometry, enzyme-linked antiglobulin tests, solid phase, or direct Polybrene. Use of non-routine reagents. The causative antibody may be IgM or IgA, not detected by routine antiglobulin reagents. Anti IgG, anti-C3d, and combined anti-C3b-C3d reagents are the only licensed products available currently to demonstrate agglutination with human red cells.[9]

Technical advances like use of gel cards to perform DAT and use of more sensitive monospecific reagents can help us reduce the number of false negative cases.[6]Many studies including an Indian study done in Pune prove the many advantages of using the Gel card technique for DAT and IAT including, simplicity, reliability, reproducibility, stability, and increased sensitivity.[10]

However, as the inclusion criterion for the present series was that the cases be DAT positive, such cases were not considered.

CONCLUSION

Study of a single large series of 175 patients from one tertiary institution showed the following.

AIHA has a female predilection and patients present commonly in the second and third decades.

Secondary AIHA is more common, with connective tissue disorders being the most often underlying disease.

Primary AIHA cases presented with severe anemia and hepato-splenomegaly; emphasizing the correlation between etiology and severity of presentation.

Laboratory evidence of hemolysis is more marked in primary AIHA.

Source of Support:

Nil

Conflict of Interest:

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemias. In: Robert H, Edward JB, Sanford JS, Bruce F, Harvey JC, Leslie ES, eds. Haematology: Basic Principles and Practice (3rd). New York: Churchill Livingston; 2000. p. :661-730.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinico-hematological spectrum of auto-immune hemolytic anemia: An Indian experience. J Assoc Physicians India. 1996;44:112-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults: Retrospective analysis of 83 cases. Rev Med Interne. 2002;23:901-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia: Review of 200 cases studied in a period of 20 years (1970-1989) Sangre (Barc). 1992;37:265-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gel test application for IgG subclass detection in autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Vox Sang. 1997;72:233-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quantitation of IgG on Erythrocytes: Correlation of number of IgG molecules per cell with the strength of the direct and indirect antiglobulin tests. Vox Sang. 1984;47:73-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grand rounds: Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:346-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technical Manual of American Association of Blood Banks. (12th). Maryland: Bathesda; 1996. p. :379-410.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of gel based technique for Coomb's test. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006;49:370-2.

- [Google Scholar]