Translate this page into:

Faropenem for the management of infectious diseases – A systematic review of in vitro susceptibility tests and clinical studies

*Corresponding author: Amitrajit Pal, Department of Medical Affairs, Alkem Laboratories Ltd., Mumbai, Maharashtra, India amitrajit.pal@alkem.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Pal A, Pawar D, Sharma A. Faropenem for the management of infectious diseases – A systematic review of in vitro susceptibility tests and clinical studies. J Lab Physicians. 2025;17:1-17. doi: 10.25259/JLP_215_2024

Abstract

This comprehensive review aimed to understand the activity and resistance pattern of faropenem compared to other antimicrobial agents. A literature search was performed using the PubMed database to identify studies published in the English language. The inclusion criteria were clinical studies involving adults and/or children with respiratory or urinary tract infections that evaluated faropenem use and resistance patterns compared to other antibiotics, in inpatient, outpatient, and/or preclinical settings. In vitro studies reporting the activity of faropenem against clinical isolates of bacteria were included in the study. Of 327 identified articles, two clinical and 21 in vitro studies were considered eligible. The clinical studies, which included adult patients with acute bacterial sinusitis, showed improvement with faropenem compared to cefuroxime. The in vitro studies indicated the activity of faropenem against Gram-positive (e.g., Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Clostridium, and Enterococcus) and Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Hemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli, and Proteus, Pseudomonas, Citrobacter, and Bacteroides species) compared to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid combination, cefpodoxime, levofloxacin, and azithromycin. Faropenem also showed activity against β-lactamase–producing and penicillin-, ampicillin-, and methicillin-resistant strains. Faropenem exhibited antimicrobial activity against a broad spectrum of bacterial pathogens, including resistant strains. Furthermore, faropenem has the potential to treat community-acquired infections, particularly respiratory tract infections.

Keywords

Aerobes

Anaerobes

Clinical studies

Faropenem

Gram-negative

Gram-positive

In vitro studies

INTRODUCTION

Infectious disease is a serious and re-emerging threat to life, causing approximately an estimated 10 million annual deaths.[1] Antimicrobial agents play a crucial role in transforming the therapeutic paradigm and are the second most prescribed drug category.[2] These agents inhibit bacterial growth by disrupting numerous molecular structures within or on the surface of bacteria. However, their increased use and misuse have led to the development of resistance.[1,3] Resistance is most commonly caused by the expression of bacterial β-lactamases, reduced target affinity to the modified penicillin-binding proteins, impaired entry, increased efflux, and a scarcity of effective antimicrobials.[3,4] To overcome these challenges, new targets and antibiotics are needed.[5]

Penems, a class of antimicrobials, are known for their broad antibacterial activity and intrinsic stability against β-lactamases, making them effective against resistant strains.[4] Based on their antibacterial spectra, penems are divided into two subclasses: carbapenem (including doripenem, ertapenem, imipenem, and meropenem) covers hospital pathogens, and faropenem, a novel oral penem with a low resistance propensity, is effective against community pathogens.[4,6]

Faropenem inhibits penicillin-binding proteins, which is crucial for maintaining cell wall structural integrity during growth and replication.[7] Its bioavailability ranges from 72% to 84% and its plasma protein binding, from 90% to 95%.[6] Faropenem shows bactericidal activity against respiratory pathogens, including methicillin-susceptible staphylococci, penicillin-susceptible/-resistant streptococci, and other aerobic and anaerobic Gram-positive pathogens[4] In India, oral faropenem is approved in 2008 for treating infections such as acute bacterial sinusitis, acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, community-acquired pneumonia, and uncomplicated skin and skin-structure infections.[8]

Several in vitro studies reported the antimicrobial activity (in terms of minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC]) of faropenem against various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial isolates from children[9-11] and adults.[11,12] The activity of faropenem was also reported against 16 penicillin-susceptible and 26 penicillin-intermediate resistant or resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae from both adults and children.[11] Another in vitro study showed the activity of faropenem against Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates and also against respiratory pathogens including S. pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Hemophilus influenzae.[13-16] Clinical studies including patients with respiratory tract infections showed the role of faropenem against S. pneumoniae, M. catarrhalis, and H. influenzae associated with community-acquired sinusitis.[17,18] A systematic review including ten clinical studies of oral penems for treating Enterobacterales infection, reported resistance emergence following faropenem treatment.[19] In addition, broad-spectrum antibiotics such as azithromycin, second- and third-generation cephalosporins, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid combination (co-amoxiclav), and quinolones were commonly prescribed for infectious disease;[20] however, excess use of broad-spectrum antibiotics can increase the chances of multidrug resistance.[21,22] Hence, there is a need to understand both the broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and resistance pattern for faropenem compared to other antimicrobial agents.

Hence, this comprehensive systematic review of in vitro and comparative clinical studies aimed to understand the activity and resistance pattern of faropenem across a range of microbes and to compare faropenem with antimicrobial agents such as co-amoxiclav, cefpodoxime, levofloxacin, and azithromycin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research questions

We conducted a scoping review of the available literature on faropenem to answer research questions: (1) Is the clinical efficacy of faropenem comparable to other antibiotics in treating infections? (2) Is the in vitro activity of faropenem comparable to other antibiotics such as co-amoxiclav, cefpodoxime, levofloxacin, and azithromycin against clinical isolates of bacteria?

We followed the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) approach to identify eligible publications for review [Table 1]. Briefly, this included studies of patients (adult and/or children) with respiratory or urinary tract infections that evaluated faropenem use and patterns of antibiotic resistance compared to other antibiotics, in inpatient, outpatient and/or preclinical settings . In vitro studies were considered for inclusion if they reported the activity of faropenem against clinical isolates of bacterial spectrum [Supplementary Table 1].

| Criteria | For clinical studies | For in vitro studies |

|---|---|---|

| P Population |

Patients (adults and/or children) with respiratory or urinary tract infections | Estimated MIC of faropenem against various bacterial isolates |

| I Intervention |

Faropenem monotherapy | Faropenem* |

| C Comparison |

Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (co-amoxiclav), azithromycin, cefpodoxime (or any cephalosporin group of drugs), and levofloxacin | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (co-amoxiclav), azithromycin, cefpodoxime, and levofloxacin* |

| O Outcomes |

Clinical efficacy and safety | MICs (MIC50, MIC90, and MIC range) |

| S Study |

Any clinical study evaluated the efficacy of faropenem in adults or children | Any in vitro study estimated the MIC |

Search strategy

The literature search was performed using the PubMed database and keywords: Faropenem, ALP 201, BLA 857, Farom, Faropenem sodium, FRPM, RU 67655, SUN 5555, SY 5555, WY 49605, and YM 044. A random search was performed using Google Scholar.

The literature search was restricted to English-language articles published until May 18, 2024. Following the database search, the title and abstract of identified articles were screened for eligibility based on the PICOS criteria [Table 1]. Systematic literature reviews, meta-analyses, narrative reviews, non-randomized or observational studies, conference or symposia abstracts or presentations, case series, case trials, editorials, and commentaries were excluded from the study. Further, clinical studies comparing the efficacy of faropenem with other penem drugs were also excluded from this review. The screened articles finally underwent full-text review to determine eligibility for inclusion in the final dataset. Two authors (DP and AP) independently examined the titles and abstracts of the retrieved records and subsequently, the full-text articles, based on the PICOS criteria. Any discrepancies between decisions were discussed with the reviewer (AS) until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Publications that met the inclusion criteria were classified as clinical studies or in vitro studies. From clinical studies, the relevant data on study characteristics, efficacy, and safety were extracted. The data on efficacy were summarized as success rate or cure rate with treatment. The safety endpoint also recorded adverse events (AEs). From in vitro studies, the data on study characteristics, clinical isolates/pathogen, and the MIC50, MIC90, and MIC range of faropenem and other antibiotics (co-amoxiclav, cefpodoxime, azithromycin, and levofloxacin) were summarized.

RESULTS

Summary of identified studies

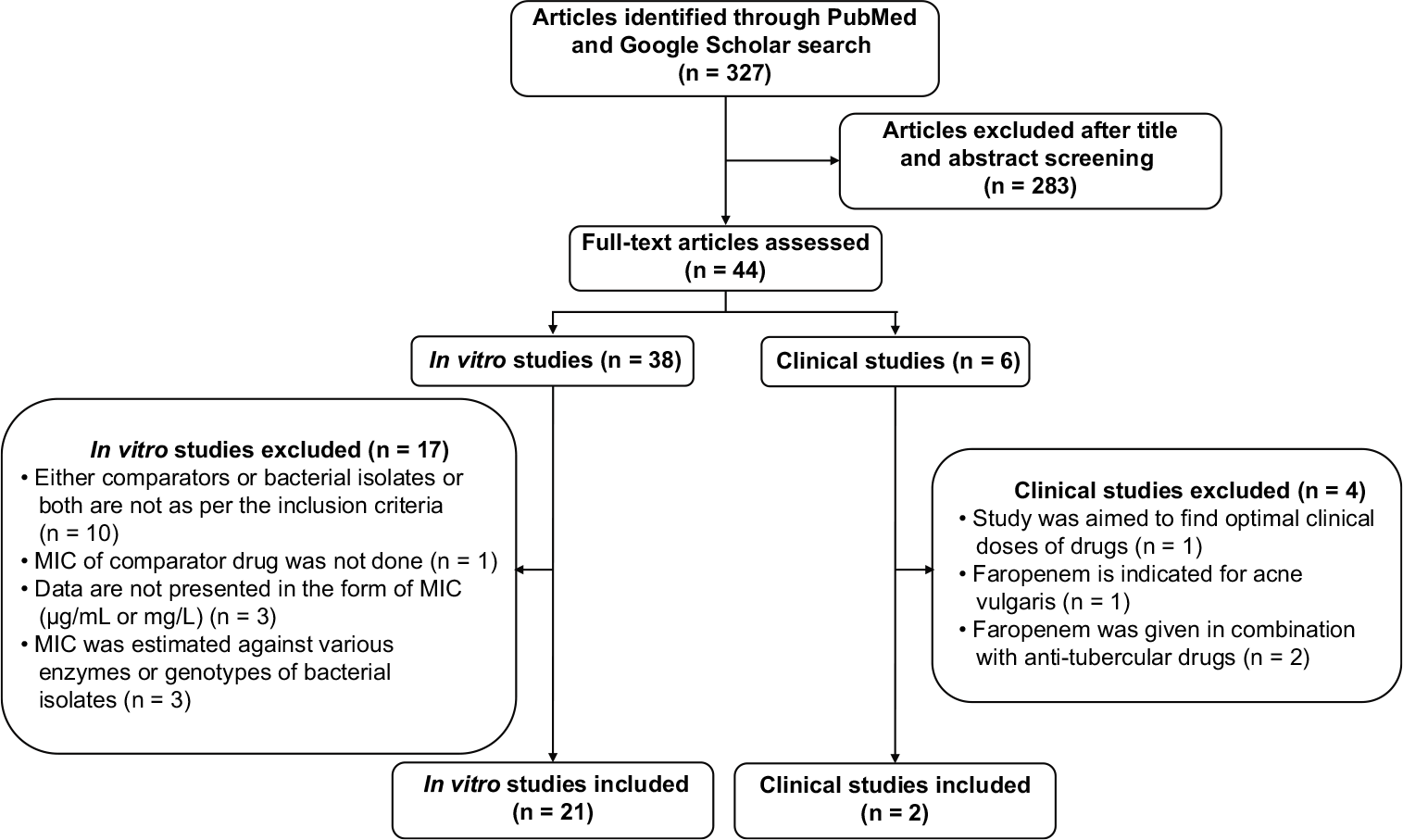

A total of 327 articles were identified in the literature search. Of these, 44 articles were selected for full-text screening, from which two clinical studies and 21 in vitro studies were considered eligible and included in the review [Figure 1].

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart. MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration

Faropenem in clinical studies

Both clinical studies were multicenter, randomized, and double-blind clinical trials involving adult patients with acute bacterial sinusitis.[17,18] A study by Siegert et al., conducted between October 2000 and June 2001, included 561 patients and showed clinical cure rates of 89% for faropenem and 88.4% for cefuroxime at 7–16 days post-therapy.[18] A study by UpChurch et al., conducted between October 2000 and November 2001, included 1106 patients and demonstrated clinical cure rates of 80.3% and 81.8% after 7 and 10 days of faropenem treatment, respectively, compared to 74.5% after 10 days of cefuroxime treatment [Table 2].[17]

| Author-Year | Study design | Country/region | Study duration | Sample size | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siegert et al., 2003[18] | Prospective, multinational, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, comparative study | France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Lithuania, Spain, Sweden | October 2000-June 2001 | n=561 | Acute bacterial maxillary sinusitis |

| Upchurch et al., 2006[17] | Prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, phase III study | USA, Canada | October 2000-November 2001 | n=1106 | Acute bacterial sinusitis |

| Author-Year | Intervention | Study population | Efficacy outcomes | Safety outcomes | |

| Siegert et al., 2003[18] | Faropenem (n=228): 300 mg twice daily orally for 7 days Cefuroxime (n=224): 250 mg twice daily orally for 7 days | Adults | Clinical cure rates: faropenem 89% and cefuroxime 88.4% Bacteriological success rate at 7-16 days posttherapy: faropenem 91.5% cefuroxime 90.8% | Drug-related AEs: faropenem 9.5% cefuroxime 10.3% | |

| Upchurch et al., 2006[17] | Faropenem (n=370): 300 mg twice daily for 7 days Faropenem (n=365): 300 mg twice daily for 10 days Cefuroxime (n=371) 250 mg twice daily for 10 days | Adults | Clinical cure rates: faropenem (7 days) 80.3% faropenem (10 days) 81.8% cefuroxime 74.5% | Drug-related AEs: faropenem (7 days) 22% faropenem (10 days) 20% cefuroxime 19% | |

AEs: Adverse events

Faropenem in in vitro studies

A total of 21 in vitro studies were included in this review.[9-16,23-35] These studies were published between 1995 and 2008, with the majority reporting MIC values (MIC50, MIC90, and MIC range; µg/mL). Among in vitro studies, the activity of faropenem was assessed against Gram-positive bacteria in 17 studies, Gram-negative bacteria in 13 studies, and resistant strains such as penicillin-susceptible/-resistant strains in eight studies, β-lactamase positive/negative strains in eight studies, and methicillin-/oxacillin-resistant strains in six studies [Tables 3 and 4; Supplementary Tables 2–4].

| Author year (country/region) comparators | Study organism/pathogen (no. of strains tested) | Faropenem | Comparator 1 (C1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | ||

| Spangler et al., 1994a[34] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Clostridium perfringens (21) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.03-4.0 | 0.25 | 2.0 | 0.125-8.0 |

| Clostridioides difficile (10) | 4.0 | 8.0 | 2.0-8.0 | 16.0 | 64.0 | 8.0-64.0 | |

| Other clostridia (16)a | 0.25 | 2.0 | 0.125-2.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 0.25-16.0 | |

| Peptostreptococci (55)b | 0.125 | 1.0 | 0.015-2.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.125-64.0 | |

| Sewell et al., 1995[35] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Enterococcus faecalis (185) | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.06->64.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.06->64.0 |

| Enterococcus faecium (11) | >64.0 | >64.0 | 1.0->64.0 | 8.0 | 64.0 | 0.5->64.0 | |

| Enterococcus spp. (101) | 1.0 | >64.0 | 0.06->64.0 | 0.5 | 8.0 | ≤0.03->64.0 | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (29) | ≤0.03 | 0.06 | ≤0.03-0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.03-0.06 | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (100) | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.03-0.25 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03-0.5 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (386) | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.03->64.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.12->64.0 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (134) | 0.12 | 2.0 | ≤0.03->64.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | ≤0.03->64.0 | |

| Staphylococcus hemolyticus (16) | 0.12 | >64.0 | ≤0.03->64.0 | 0.25 | 64.0 | 0.06-64.0 | |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus (20) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.06-1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-2.0 | |

| Staphylococci (CN) (264) | 0.12 | 4.0 | ≤0.03->64 | 1.0 | 8.0 | ≤0.03->64.0 | |

| Fuchs et al., 1995[24] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Enterococcus durans (10) | 2.0 | 16.0 | 0.06->16.0 | 0.25 | 1.0 | ≤0.006-2.0 |

| Enterococcus faecalis (10) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25-0.5 | |

| Enterococcus faecium (10) | 8.0 | >16.0 | 1.0->16.0 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 0.12-4.0 | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (15)c | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.03-0.5 | ≤0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.06-1.0 | |

| Streptococcus viridans (10) | 0.25 | 0.06 | ≤0.03-0.5 | 0.12 | 1.0 | ≤0.06-2.0 | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (15) | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.03-0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06-0.12 | |

| Groups C and G Streptococcus (20) | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | |

| Streptococcus spp. (15) | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (12) | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.06->16.0 | 0.25 | 2.0 | ≤0.06-8.0 | |

| Staphylococcus hemolyticus (10) | 4.0 | >16.0 | 0.12->16.0 | 16.0 | >16.0 | 1.0->16.0 | |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus (10) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25-0.5 | |

| Staphylococcus spp. (7)d | 0.12 | NA | 0.06-0.25 | ≤0.12 | NA | ≤0.06-0.25 | |

| Eliopoulos et al., 1995 (USA)[23] C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Enterococcus faecium (20) | 128.0 | >128.0 | 2.0->128.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 0.12-64.0 |

| Enterococcus avium (10) | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0-4.0 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.25-1.0 | |

| Enterococcus raffinosus (11) | 128.0 | 128.0 | 64.0->128.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 2.0-16.0 | |

| Enterococcus casseliflavus/gallinarum (10) | 4.0 | 8.0 | 1.0-8.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5-1.0 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis (15) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.5-4.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5-1.0 | |

| Group A streptococci (10) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.016-0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.016-0.03 | |

| Group B streptococci (10) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03–0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.06-0.12 | |

| Group C and G streptococci (9) | NA | NA | 0.016–0.03 | NA | NA | 0.016-0.06 | |

| Mortensen et al., 1995[15] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Enterococcus spp. (20) | 2.0 | >32.0 | 1.0–>32.0 | 1.0 | 16.0 | 0.5->32.0 |

| Ubukata et al., 1996[25] (Japan) C1: Cefpodoxime C2: Levofloxacin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (1283) | 0.031 | 0.5 | 0.004–4.0 | 4.0 | 32.0 | 0.063-64.0 |

| Woodcock et al., 1997[14] (UK) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Clostridium perfringens (10) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-1.0 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.06-0.25 |

| Clostridioides difficile (10) | 4.0 | 8.0 | 1.0-8.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-2.0 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis (10) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.25-4.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25-0.5 | |

| Enterococcus faecium (10) | 64.0 | >128.0 | 8.0->128.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 1.0-16.0 | |

| Group A streptococci (19) | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | |

| Group B streptococci (20) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. (19) | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.008-1.0 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.06-1.0 | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (20) | 0.008 | 0.25 | 0.004-0.5 | 0.015 | 1.0 | 0.015-2.0 | |

| Streptococcus milleri (28) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03-0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.03-0.5 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (20) | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.06->128.0 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.12->128.0 | |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus (28) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.12-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12-0.5 | |

| Wexler et al., 2002[28] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Clostridioides difficile (11) | 8.0 | 16.0 | 0.5-32.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.12-2.0 |

| Clostridium perfringens (20) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.12-1.0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12-1.0 | |

| Clostridium ramosum (10) | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.12-1.0 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12-1.0 | |

| Clostridium sordellii (10) | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12-5.0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12-0.25 | |

| Clostridium sporogenes (10) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5-1.0 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.12-0.5 | |

| Clostridium spp. (10)e | 2.0 | 8.0 | 0.5-8.0 | 0.5 | 2.00 | 0.25-8.0 | |

| Goldstein et al., 2002[27] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin |

Enterococcus spp. (10)f | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.03-1.0 | 0.125 | 0.5 | ≤0.015-0.5 |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. (16)g | 0.125 | 1.0 | ≤0.015-4.0 | 0.25 | 2.00 | ≤0.015-4.0 | |

| Streptococcus spp. (37)h | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03-0.25 | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.015-1.0 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (19) | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.06-0.5 | 0.5 | 2.00 | 0.125-4.0 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (12) | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.06-1.0 | 0.125 | 0.50 | 0.03-1.0 | |

| Staphylococci (CN) (11)1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03-1.0 | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.015-2.0 | |

| Milatovic et al., 2002[33] (Netherlands) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Enterococcus faecalis (291) | 1.00 | 8.00 | 0.06->32.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.03->32.0 |

| Enterococcus faecium (220) | >32 | >32.0 | 0.06->32.0 | 32.0 | >32.0 | 0.12->32.0 | |

| Group A Streptococci streptococci (186) | 0.03 | 0.03 | ≤0.015-0.06 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015-0.12 | |

| Group B Streptococci streptococci (163) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03-0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | ≤0.015-0.25 | |

| Streptococcus milleri (38) | 0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.015-0.12 | 0.12 | 0.25 | ≤0.015-0.25 | |

| Streptococcus viridans (191) | 0.12 | 1.0 | ≤0.015-8.0 | 0.12 | 2.0 | ≤0.015->32.0 | |

| Staphylococci (CN) (354) | 0.12 | 4.00 | <0.015->32.0 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 0.03->32.0 | |

| Milazzo et al., 2003[30] (Italy) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Peptostreptococcus spp. (11) | 0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.03-16.0 | 0.12 | 0.25 | ≤0.03-16.0 |

| Decousser et al., 2003[31] (France) C1: Levofloxacin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (194)j | 0.032 | 0.25 | 0.008-1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.25-2.0 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (60)k | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.008-1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5-2.0 | |

| Walsh et al., 2003[16] (UK) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (100) | 0.008 | 0.25 | 0.002-1.0 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.004-2.0 |

| Behra-Miellet et al., 2005[12] (France) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Clostridium perfringens (29) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.03-0.5 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03-0.12 |

| Clostridioides difficile (26) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.03-2.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.06-2.0 | |

| Gram-positive anaerobes (197) | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.015-2.0 | 0.12 | 1.0 | 0.03-2.0 | |

| Other clostridium (22)l | 0.12 | 2.0 | 0.015-2.0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.03-2.0 | |

| Stone et al., 2007[10] (Israel) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (393) | NA | 0.5 | ≤0.004-1.0 | NA | 2.0 | ≤0.015-4.0 |

| Stone et al., 2007[10] (Costa Rica) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (168) | NA | 0.06 | ≤0.004-2.0 | NA | 0.12 | ≤0.015-16.0 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (30) | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.008-0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | |

| Critchley et al., 2008[9] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (393) | NA | 1.0 | NA | NA | 8.0 | NA |

| Author year (country/region) comparator | Study organism/pathogen (no. of strains tested) | Comparator 2 (C2) | Comparator 3 (C3) | ||||

| MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | ||

| Spangler et al., 1994a[34] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Clostridium perfringens (21) | 1.0 | 8.0 | 0.06->32.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Clostridioides difficile (10) | >32.0 | >32.0 | 16.0->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Other clostridia (16)a | 8.0 | >32.0 | 0.125->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Peptostreptococci (55)b | 0.5 | 16.0 | 0.06-32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Sewell et al., 1995[35] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Enterococcus faecalis (185) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Enterococcus faecium (11) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Enterococcus spp. (101) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (29) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (386) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (134) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus hemolyticus (16) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus (20) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococci (CN) (264) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Fuchs et al., 1995[24] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Enterococcus durans (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Enterococcus faecalis (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Enterococcus faecium (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (15)c | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus viridans (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (15) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Groups C and G Streptococcus (20) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus spp. (15) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (12) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus hemolyticus (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus spp. (7)d | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Eliopoulos et al., 1995 (USA)[23] C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Enterococcus faecium (20) | >128.0 | >128.0 | >128.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Enterococcus avium (10) | 8.0 | 64.0 | 8.0-128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Enterococcus raffinosus (11) | >128.0 | >128.0 | >128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Enterococcus casseliflavus/gallinarum (10) | >128.0 | >128.0 | 32.0->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Enterococcus faecalis (15) | >128.0 | >128.0 | >128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Group A streptococci (10) | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.008-0.016 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Group B streptococci (10) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03-0.25 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Group C and G streptococci (9) | NA | NA | 0.016-0.03 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Mortensen et al., 1995[15] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Enterococcus spp. (20) | >32.0 | >32.0 | >32.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ubukata et al., 1996[25] (Japan) C1: Cefpodoxime C2: Levofloxacin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (1283) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.25-64.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Woodcock et al., 1997[14] (UK) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Clostridium perfringens (10) | 8.0 | 16.0 | 1.0-16.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Clostridioides difficile (10) | 128.0 | >128.0 | 128.0->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Enterococcus faecalis (10) | 8.0 | >128.0 | 2.0->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Enterococcus faecium (10) | >128.0 | >128.0 | 128.0->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Group A streptococci (19) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Group B streptococci (20) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03-0.06 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. (19) | 1.0 | 8.0 | 0.25-32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (20) | 0.03 | 2.0 | 0.03-4.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus milleri (28) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.03-32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (20) | 2.0 | 16.0 | 0.25->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus (28) | 4.0 | 8.0 | 1.0-8.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Wexler et al., 2002[28] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Clostridioides difficile (11) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Clostridium perfringens (20) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Clostridium ramosum (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Clostridium sordellii (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Clostridium sporogenes (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Clostridium spp. (10)e | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Goldstein et al., 2002[27] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin |

Enterococcus spp. (10)f | 0.5 | 1.0 | ≤0.06-1.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. (16)g | 0.5 | 4.0 | ≤0.06-8.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus spp. (37)h | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5-2.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (19) | 0.125 | 0.25 | ≤0.06-0.25 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (12) | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.125-8.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococci (CN) (11)i | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125-1.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Milatovic et al., 2002[33] (Netherlands) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Enterococcus faecalis (291) | >32.0 | >32.0 | 0.25->32.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Enterococcus faecium (220) | >32.0 | >32.0 | 0.25->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Group A Streptococci streptococci (186) | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015-0.12 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Group B Streptococci streptococci (163) | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.015-0.12 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus milleri (38) | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.015-0.5 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Streptococcus viridans (191) | 0.25 | 4.0 | ≤0.015->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Staphylococci (CN) (354) | 4.0 | >32.0 | 0.06->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Milazzo et al., 2003[30] (Italy) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Peptostreptococcus spp. (11) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Decousser et al., 2003[31] (France) C1: Levofloxacin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (194)j | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (60)k | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Walsh et al., 2003[16] (UK) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (100) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.12-2.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Behra-Miellet et al., 2005[12] (France) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Clostridium perfringens (29) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Clostridioides difficile (26) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Gram-positive anaerobes (197) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Other clostridium (22)l | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Stone et al., 2007[10] (Israel) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (393) | NA | 1.0 | 0.25-2.0 | NA | ≥8.0 | ≤0.03-≥8.0 |

| Stone et al., 2007[10] (Costa Rica) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (168) | NA | 1 | 0.5-1.0 | NA | 4.0 | ≤0.03->8.0 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (30) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-2.0 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.06-0.12 | |

| Critchley et al., 2008[9] C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Streptococcus pneumoniae (393) | NA | 1.0 | NA | NA | >16.0 | NA |

All MICs are presented in µg/mL. The number mentioned in parentheses after each bacterium denotes no. of strains tested. aIncludes Clostridium ramosum (2), Clostridium tertium (2), Clostridium innocuum (1), Clostridium sporogenes (1), Clostridium butyricum (2), Clostridium cadaveris (2), Clostridium bifermentans (2), Clostridium sordellii (1), Clostridium septicum (1), Clostridium histolyticum (1), Clostridium paraperfringens (1). bIncludes Peptostreptococcus asaccharolyticus strains (2), Peptostreptococcus magnus (14), Peptostreptococcus prevotii (1), Peptostreptococcus micros (2), Peptostreptococcus anaerobius (6), Peptostreptococcus tetradius (21), Peptostreptococcus productus (3), Peptostreptococci spp. (3), Staphylococcus intermedius (3). cIncludes penicillin-intermediate strains (2), penicillin-susceptible strains (13). dIncludes Staphylococcus hominis (2), Staphylococcus simulans (3), Staphylococcus warneri (2). eIncludes Clostridium butyricum (3), Clostridium clostridioforme (4), Clostridium innocuum (3). fIncludes Enterococcus avium (1), Enterococcus durans (3), Enterococcus faecalis (6). gIncludes Peptostreptococcus anaerobius (5), Peptostreptococcus asaccharolyticus (1), Peptostreptococcus ivorii (1), Peptostreptococcus magnus (2), Peptostreptococcus micros (4), Peptostreptococcus prevotii (2), Peptostreptococcus tetradius (1). hIncludes Streptococcus anginosus (7), Streptococcus constellatus (6), Streptococcus intermedius (7), Streptococcus mitis (6), Streptococcus mutans (1), Streptococcus oralis (3), Streptococcus salivarius (2), Streptococcus sanguis (2), Aerococcus viridans (1), Stomatococcus mucilaginosus (2). iIncludes Staphylococcus hyicus (2), Staphylococcus intermedius (5), Kocuria kristinae (1), Micrococcus spp. (2), Rhodococcus spp. (1). j Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated from blood cultures of adult patients. k Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated from blood cultures of children. lIncludes Clostridium baratii (1), Clostridium bifermentans (1), Clostridium fallax (2), Clostridium histolyticum (1), Clostridium ramosum (3), Clostridium sphenoides (2), Clostridium sporogenes (2), Clostridium sordelii (4), Clostridium septicum (1), Clostridium spp. (5). Co-amoxiclav: Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid combination, CN: Coagulase negative, MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration, NA: Not available

| Author year (country/region) comparators | Study organism/pathogen (no. of strains tested) | Faropenem | Comparator 1 (C1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | ||

| Spangler et al., 1994a[34] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Bacteroides fragilis (30) | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.06-4.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.25-4.0 |

| Sewell et al., 1995[35] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Citrobacter diversus (8) | 0.5 | NA | 0.25-1.0 | 2.0 | NA | 1.0-4.0 |

| Citrobacter freundii (41) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.25->64.0 | 64.0 | >64.0 | ≤0.03->64.0 | |

| Escherichia coli (817) | 0.5 | 1.0 | ≤0.03-16.0 | 4.0 | 32.0 | 0.5->64.0 | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca (45) | 0.5 | 4.0 | 0.25-64.0 | 4.0 | 16.0 | 0.12-32.0 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (186) | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.12-4.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 | 0.25-64.0 | |

| Proteus mirabilis (52) | 4.0 | 8.0 | 0.25-16.0 | 1.0 | 32.0 | 0.12->64.0 | |

| Proteus vulgaris (9) | 2.0 | NA | 0.5-16.0 | 16.0 | NA | 2.0-64.0 | |

| Pseudomonas spp. (8) | 64.0 | NA | 2.0->64.0 | 64.0 | NA | 1.0->64.0 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (246) | >64.0 | >64.0 | 8.0->64.0 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 32.0->64.0 | |

| Fuchs et al, 1995[24] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Citrobacter diversus (10) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25-0.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0-8.0 |

| Citrobacter freundii (21) | 2.0 | 4.0 | 0.25-4.0 | >16.0 | >16.0 | 8.0->16.0 | |

| Escherichia coli (25) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25-2.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 | 1.0-16.0 | |

| Klebsiella spp. (25) | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.25-4.0 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 1.0-16.0 | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis (15) | 0.12 | 0.5 | ≤0.03-0.5 | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06-0.25 | |

| Neisseria meningitidis (10) | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | 0.12 | 0.12 | ≤0.06-0.12 | |

| Proteus mirabilis (10) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0-2.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-1.0 | |

| Proteus vulgaris (10) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0-2.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 4.0-16.0 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (15) | >16.0 | >16.0 | >16.0 | >16.0 | >16.0 | >16.0 | |

| Pseudomonas spp. (20)a | >16.0 | >16.0 | 16.0->16.0 | >16.0 | >16.0 | 1.0->16.0 | |

| Salmonella spp. (15)b | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.12-1.0 | 0.5 | >16.0 | 0.25->16.0 | |

| Shigella spp. (20)c | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12-1.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 | 1.0-16.0 | |

| Eliopoulos et al., 1995[23] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Bacteroides fragilis (30) | 0.25 | 4.0 | 0.03-8.0 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 0.25-8.0 |

| Citrobacter freundii (20) | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.5-16.0 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 16.0-128.0 | |

| Escherichia coli (30) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.5-4.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 4.0-32.0 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (20) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.5-4.0 | 4.0 | 16.0 | 1.0-32.0 | |

| Proteus mirabilis (20) | 4.0 | 4.0 | 1.0-8.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0-16.0 | |

| Proteus vulgaris (10) | 8.0 | 8.0 | 4.0-8.0 | 16.0 | 32.0 | 8.0-32.0 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10) | >128.0 | >128.0 | 32.0->128.0 | >128.0 | >128.0 | >128.0 | |

| Salmonella spp. (13) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.5-4.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.5-32.0 | |

| Mortensen et al., 1995[15] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Citrobacter freundii (12) | 1.0 | 8.0 | 0.06-8.0 | >32.0 | >32.0 | 8.0->32.0 |

| Escherichia coli (67) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-2.0 | 16.0 | 32.0 | 1.0->32.0 | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca (23) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-2.0 | 16.0 | >32.0 | 8.0->32.0 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (36) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.25-32.0 | 8.0 | >32.0 | 1.0->32.0 | |

| M. catarrkalis (27) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.03-1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-2.0 | |

| Proteus mirabilis (17) | 4.0 | 8.0 | 2.0-8.0 | 1.0 | 32.0 | 1.0-32.0 | |

| Salmonella enteritidis (25) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-1.0 | 1.0 | 32.0 | 1.0-32.0 | |

| Shigella spp. (11) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.5-1.0 | 32.0 | 32.0 | 32.0->32.0 | |

| Woodcock et al., 1997[14] (UK) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Bacteroides fragilis (24) | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.12-32.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.25-4.0 |

| Citrobacter spp. (10)d | 0.5 | 4.0 | 0.25-4.0 | 16.0 | 64.0 | 1.0-128.0 | |

| Escherichia coli (71) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.06-8.0 | 4.0 | 16.0 | 0.5-32.0 | |

| Haemophilus influenzae (35) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-2.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.25-4.0 | |

| Klebsiella spp. (47) | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.06-8.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 | 0.5-32.0 | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis (35) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.03-1.0 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.015-1.0 | |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae (35) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.008-0.25 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.06-2.0 | |

| Neisseria meningitides (10) | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| Proteus mirabilis (49) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.25-2.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.25-16.0 | |

| Proteus vulgaris (20) | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.5-4.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0-8.0 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (9) | >128.0 | >128.0 | 8.0->128.0 | 64.0 | 128.0 | 32.0->128.0 | |

| Providencia stuartii (20) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.06-4.0 | 64.0 | 128.0 | 2.0->128.0 | |

| Salmonella spp. (5) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 16.0 | 0.5-16.0 | |

| Shigella spp. (5) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25-0.5 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 1.0-8.0 | |

| Wexler et al, 2002[28] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Bacteroides fragilis (68) | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.12-64.0 | 0.5 | 8.0 | 0.25-64.0 |

| Milatovic et al., 2002[33] (Netherlands) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Escherichia coli (323) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.25-32.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 2.0->32.0 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis (307) | 0.12 | 0.5 | ≤0.015-1.0 | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.015-0.5 | |

| Proteus mirabilis (282) | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.25-16.0 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 0.5->32.0 | |

| Proteus vulgaris (85) | 4.0 | 8.0 | 0.5-16.0 | 4.0 | 16.0 | 1.0->32.0 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (228) | >32.0 | >32.0 | 2->32.0 | >32.0 | >32.0 | 2.0->32.0 | |

| Walsh et al., 2003[16] (UK) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin |

Haemophilus influenzae (100) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.06-4.0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.016-2.0 |

| Jones et al. 2005 [13] (USA) C1: Levofloxacin C2: Azithromycin |

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (265) | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.008-0.5 | 0.016 | 4.0 | ≤0.008->4.0 |

| Behra-Miellet et al., 2005[12] (France) C1: Levofloxacin C2: Azithromycin |

Bacteroides fragilis (85) | 0.01 | 0.5 | 0.015->128.0 | 0.25 | 4.0 | 0.06->64.0 |

| Gram-negative anaerobes (265) | 0.12 | 1.0 | 0.015->128.0 | 0.25 | 8.0 | 0.03->64.0 | |

| Stone et al., 2007[10] (Israel) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Haemophilus influenzae (367) | NA | 0.25 | 0.015-4.0 | NA | 1.0 | 0.12-8.0 |

| Stone et al., 2007[10] (Costa Rica) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Haemophilus influenzae (187) | NA | 0.5 | 0.008-4.0 | NA | 1.0 | 0.03-2.0 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis (43) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.008-0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.015-0.5 | |

| Author year (country/region) comparators | Study organism/pathogen (no. of strains tested) | Comparator 2 (C2) | Comparator 3 (C3) | ||||

| MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | ||

| Spangler et al., 1994a[34] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Bacteroides fragilis (30) | 32.0 | >32.0 | 0.5->32.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Sewell et al., 1995[35] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Citrobacter diversus (8) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Citrobacter freundii (41) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Escherichia coli (817) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca (45) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (186) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus mirabilis (52) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus vulgaris (9) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Pseudomonas spp. (8) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (246) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Fuchs et al., 1995[24] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Citrobacter diversus (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Citrobacter freundii (21) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Escherichia coli (25) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Klebsiella spp. (25) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis (15) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Neisseria meningitidis (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus mirabilis (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus vulgaris (10) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (15) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Pseudomonas spp. (20)a | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Salmonella spp. (15)b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Shigella spp. (20)c | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Eliopoulos et al., 1995[23] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Bacteroides fragilis (30) | 32.0 | >128.0 | 4.0->128.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Citrobacter freundii (20) | 4.0 | >128.0 | 2.0->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Escherichia coli (30) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.12-2.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (20) | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.06->128 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus mirabilis (20) | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.06-1.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus vulgaris (10) | 2.0 | >128.0 | 0.25->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10) | >128.0 | >128.0 | >128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Salmonella spp. (13) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.25-2.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Mortensen et al., 1995[15] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Citrobacter freundii (12) | 8.0 | >32.0 | 0.25->32.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Escherichia coli (67) | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.06-32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca (23) | >16.0 | >16.0 | >16.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (36) | 0.25 | 32.0 | 0.06->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| M. catarrkalis (27) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.25-2.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus mirabilis (17) | 0.06 | 8.0 | 0.03->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Salmonella enteritidis (25) | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.25-1.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Shigella spp. (11) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.5-1.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Woodcock et al., 1997[14] (UK) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Bacteroides fragilis (24) | 64.0 | >128.0 | 8.0->128.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Citrobacter spp. (10)d | 1.0 | 64.0 | 0.25->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Escherichia coli (71) | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.06->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Haemophilus influenzae (35) | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.06-0.5 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Klebsiella spp. (47) | 0.12 | 4.0 | 0.015-128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis (35) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.12-1.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae (35) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.002-0.06 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Neisseria meningitides (10) | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.002-0.004 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus mirabilis (49) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03-0.12 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus vulgaris (20) | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.06-1.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (9) | >128.0 | >128.0 | 128.0->128.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Providencia stuartii (20) | 0.06 | 2.0 | 0.015-16.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Salmonella spp. (5) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.5-2.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Shigella spp. (5) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25-0.5 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Wexler et al., 2002[28] (USA) C1: Co-amoxiclav |

Bacteroides fragilis (68) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Milatovic et al., 2002[33] (Netherlands) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Cefpodoxime |

Escherichia coli (323) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.12->32.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Moraxella catarrhalis (307) | 0.5 | 1.0 | ≤0.015-1.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus mirabilis (282) | 0.06 | 8.0 | ≤0.015->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Proteus vulgaris (85) | 0.5 | 16.0 | 0.06->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (228) | >32.0 | >32.0 | 16.0->32.0 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Walsh et al., 2003[16] (UK) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin |

Haemophilus influenzae (100) | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.004-1.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Jones et al. 2005[13] (USA) C1: Levofloxacin C2: Azithromycin |

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (265) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.03-2.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Behra-Miellet et al., 2005[12] (France) C1: Levofloxacin C2: Azithromycin |

Bacteroides fragilis (85) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gram-negative anaerobes (265) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Stone et al., 2007[10] (Israel) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Haemophilus influenzae (367) | NA | 0.015 | ≤0.004-0.03 | NA | 2.0 | 0.25-4.0 |

| Stone et al., 2007[10] (Costa Rica) C1: Co-amoxiclav C2: Levofloxacin C3: Azithromycin |

Haemophilus influenzae (187) | NA | 0.015 | ≤0.004-1.0 | NA | 2.0 | 0.12-4.0 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis (43) | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.004-0.5 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03-0.5 | |

All MICs are presented in pg/mL. The number mentioned in parentheses after each bacterium denotes no. of strains tested. aIncludes Pseudomonas cepacia (5), Pseudomonas fluorescens (6), Pseudomonas putida (4), Pseudomonas stutzeri (5). bIncludes Salmonella enteritidis (10), Salmonella typhi (5). cIncludes Shigella dysenteriae (5), Shigella flexneri (5), Shigella boydii (5), Shigella sonnei (5). dIncludes Citrobacter freundii (6), Citrobacter diversus (4). Co-amoxiclav: Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid combination, MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration, NA: Not available

Faropenem activity against Gram-positive bacterial isolates

The most frequently studied bacterial isolates were S. pneumonia, followed by Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Enterococcus faecium [Table 3].

The MIC90 of faropenem obtained in different studies varied from 0.015 to 1 µg/mL against Streptococcus species.[9,10,14,16,23-25,27,31,33,35] However, this was lower than that for comparators: co-amoxiclav, from ≤0.015 to 8 µg/mL;[9,10,14,16,23,24,27,33,35] cefpodoxime, from ≤0.015 to 32 µg/mL;[14,23,25,33] levofloxacin, from 1 to 2 µg/mL;[9,10,16,25,27,31] and azithromycin, from 0.12 to >16 µg/mL.[9,10]

The MIC90 of faropenem ranged from 0.06 to >64 µg/mL against Staphylococcus species,[14,24,27,33,35] which was lower than that of co-amoxiclav (0.25–64 µg/mL),[14,24,27,33,35] cefpodoxime (8–>32 µg/mL),[14,33] and levofloxacin (0.25– 1 µg/mL).[27]

Faropenem showed good activity against Clostridium species, with the MIC90 ranging from 0.12 to 16 µg/mL,[12,14,28,34] whereas the reported MIC90 ranges for co-amoxiclav (0.03– 64 µg/mL)[12,14,28,34] and cefpodoxime (8–>128 µg/mL)[14,34] were broader than that for faropenem.

The MIC90 against Enterococcus species ranged from 1 to >128 µg/mL for faropenem,[14,15,23,24,27,33,35] from >32 to >128 µg/mL for cefpodoxime,[14,15,23,33] and from 0.5 to 64 µg/mL for co-amoxiclav.[14,15,23,24,27,33,35]

Faropenem activity against Gram-negative bacterial isolates

Commonly studied Gram-negative bacterial isolates were H. influenzae, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis [Table 4].

In in vitro studies, the MIC90 of faropenem for E. coli ranged from 0.5 to 1 µg/mL[14,15,23,24,33,35] and for Proteus species from 2 to 8 µg/mL:[14,15,23,24,33,35] these figures were lower than those for co-amoxiclav (MIC90 for E. coli, from 8 to 32 µg/mL; for Proteus species, from 1 to 32 µg/mL)[14,15,23,24,33,35] and cefpodoxime (MIC90 for E. coli, from 0.5 to 2 µg/mL and Proteus species, from 0.06 to >128 µg/mL.[14,15,23,33]

The MIC90 of faropenem ranged from 1 to 4 µg/mL against Klebsiella species,[14,15,23,24,35] while the MIC90 reported for coamoxiclav was 8–>32 µg/mL[14,15,23,24,35] and for cefpodoxime 1–32 µg/mL.[14,15,23]

Against Pseudomonas species, faropenem had the lowest reported MIC90 (0.5 µg/mL)[14,23,24,33,35] compared to co-amoxiclav (16 µg/mL)[14,23,24,33,35] and cefpodoxime (>32 µg/mL).[14,23,33] The maximum reported values for the MIC90 of faropenem,[14,23,24,33,35] co-amoxiclav,[14,23,24,33,35] and cefpodoxime[14,23,33] were similar (>128 µg/mL).

Further, faropenem showed good activity against Citrobacter species, with the lowest MIC90 of 0.5 µg/mL to the highest of 8 µg/mL[14,15,23,24,35] and against Bacteroides species, from 0.5 µg/mL to 4 µg/mL,[12,14,23,28,34] compared to co-amoxiclav and cefpodoxime. The reported MIC90 of co-amoxiclav against Citrobacter species ranged from 2 µg/mL to >64 µg/mL[14,15,23,24,35] and against Bacteroides species from 2 µg/mL to 8 µg/mL,[12,14,23,28,34] whereas the MIC90 of cefpodoxime against Citrobacter species ranged from >32 µg/mL to >128 µg/mL[14,15,23] and against Bacteroides species from >32 µg/mL to >128 µg/mL.[14,23,34]

Faropenem activity against resistant species

The MIC90 of faropenem against penicillin-susceptible Streptococcus species ranged from 0.008 to 0.12 µg/mL[10,11,15,23,29,31,33,35] and was lower than co-amoxiclav (≤0.03–0.5 µg/mL),[10,15,23,29,33,35] cefpodoxime (0.03–0.5 µg/mL),[15,23,33] azithromycin (0.06–>128 µg/mL),[10,11] and levofloxacin (1 µg/mL).[10,11,29,31] Against penicillin-intermediate resistant or resistant strains of S. pneumoniae, the lowest reported MIC90 (0.25 µg/mL) was similar for faropenem[10,11,15,23,29,31,33,35] and cefpodoxime,[15,23,33] whereas the highest reported MIC90 (8 µg/mL) for faropenem[10,11,15,23,29,31,33,35] was similar to co-amoxiclav;[10,15,23,29,33,35] lower than cefpodoxime (16 µg/mL)[15,23,33] and azithromycin (>128 µg/mL);[10,11] and higher than levofloxacin (1 µg/mL) [Supplementary Table 2].[10,11,29,31]

The MIC90 of faropenem ranged from 0.25 to 4 µg/mL against β-lactamase negative strains of H. influenzae,[10,15,24,26,29,32,33,35] whereas that of co-amoxiclav ranged from 0.5 to 8 µg/mL).[10,15,24,26,29,32,33,35] The MIC90 of cefpodoxime was 0.12 µg/mL;[15,26,32,33] levofloxacin, 0.015 µg/mL;[10,29] and azithromycin, 2 µg/mL;[10,26] all were lower compared to faropenem. The reported MIC90 of faropenem against β-lactamase positive strains of H. influenzae ranged from 0.25 to 64 µg/mL,[10,15,24,26,29,32,33,35] that was broader than that of all comparators: co-amoxiclav (1–2 µg/mL);[10,15,24,26,29,32,33,35] cefpodoxime (0.12–0.25 µg/mL);[15,26,32,33] levofloxacin (0.015 µg/mL);[10,29] and azithromycin (2 µg/mL).[10,26] The MIC90 of faropenem ranged from 0.12 to 0.5 µg/mL against β-lactamase–negative and from 0.25 to 1 µg/mL against β-lactamase–positive strains of M. catarrhalis;[26,29,35] for coamoxiclav, the MIC90 ranges were 0.03–0.5 µg/mL and 0.25– 0.5 µg/mL, respectively [Supplementary Table 3].[26,29,35]

The MIC90 of faropenem ranged from 0.1 to 0.25 µg/mL against methicillin- or oxacillin-sensitive S. aureus,[14,15,23,24,33,35] which was lower than the MIC90 of co-amoxiclav (0.5– 4 µg/mL)[14,15,23,24,33,35] and cefpodoxime (4–16 µg/mL).[14,15,23,33] However, against methicillin- or oxacillin-resistant S. aureus, the MIC90 of faropenem and comparators was similar: faropenem, 2–>128 µg/mL;[14,15,23,24,33,35] co-amoxiclav, 8–64 µg/mL;[14,15,23,24,33,35] and cefpodoxime, >32–>128 µg/mL [Supplementary Table 4].[14,15,23,33]

DISCUSSION

This comprehensive systematic review of 21 in vitro studies and two clinical comparative studies demonstrates the antimicrobial activity and resistance pattern of faropenem compared to other antibiotics against a variety of bacterial isolates. Two clinical comparative studies of faropenem versus other antibiotics reported a higher bacteriological success rate with faropenem than cefuroxime in treating respiratory infection (acute bacterial maxillary sinusitis) in adults,[18] and the 7-day and 10-day twice-daily treatment regimen of faropenem (300 mg) was non-inferior to the standard 10-day twice-daily cefuroxime (250 mg) regimen in terms of clinical cure rates and drug-related AEs.[17] Furthermore, in vitro studies identified in this review have demonstrated the good activity of faropenem, in terms of MIC, compared to co-amoxiclav, cefpodoxime, levofloxacin, and azithromycin against a wide bacterial spectrum. The findings of this review suggest the potential of faropenem against Gram-positive and Gram-negative aerobes and anaerobes, especially community pathogens causing respiratory tract infections. Bacterial strains producing β-lactamase and other strains resistant to penicillin, methicillin, and oxacillin were also found to be susceptible to faropenem.

A prospective, multinational, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, comparative study by Siegert et al., included 561 adult patients with acute bacterial maxillary sinusitis, with the predominant causative organisms S. pneumoniae (47.1%), H. influenzae (30.1%), S. aureus (14.7%), and M. catarrhalis (8.8%). The study demonstrated a higher bacteriological success rate after 7-10 days post-treatment with twice-daily faropenem 300 mg (91.5%) than cefuroxime axetil 250 mg (90.8%), with clinical cure rates of 89% with faropenem and 88.4% with cefuroxime. Drug-related AEs were found to be similar between faropenem (9.5%) and cefuroxime (10.3%).[18] Another prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, phase III study by UpChurch et al., including 1106 patients with acute bacterial sinusitis, compared two regimens of faropenem 300 mg twice daily for 7 days and 10 days, with one of cefuroxime 250 mg twice daily for 10 days. This study reported the efficacy as clinical cure rates of faropenem (80.3% for 7 days and 81.8% for 10 days) versus cefuroxime axetil (74.5%), which suggests that both faropenem regimens were non-inferior to the standard 10-day cefuroxime regimen in terms of efficacy and safety.[17] Cefuroxime axetil has low oral bioavailability (about 36–52%), which may affect the clinical efficacy despite its low MIC against the bacterial strains causing the infection,[36,37] whereas faropenem demonstrates high oral bioavailability (70–80%),[19] which could be responsible for higher bacterial and clinical success rate. The study also showed that patients treated with cefuroxime axetil had liver function abnormality, which is a known effect of β-lactams, and the evidence of hepatic enzyme elevation by cefuroxime has been shown by previous evidence.[18,36] Further, there are limited comparative clinical studies of faropenem versus other antibiotics; hence, drawing conclusions on the therapeutic response of faropenem versus other antibiotics is difficult and could point to future avenues of research.

The MIC values serve as the basis for assessing the degree of susceptibility or resistance of pathogens to a specific antibiotic[38] and help to select the most appropriate treatment.[39] A study by Stone et al. demonstrated the activity of faropenem against respiratory pathogens such as S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae, isolated from middle ear fluid, compared to other antimicrobial agents including coamoxiclav, azithromycin, and levofloxacin. Faropenem also showed activity against M. catarrhalis and Streptococcus pyogenes.[10] Further, faropenem showed potent anti-gonococcal activity against N. gonorrhoeae, regardless of resistance phenotype.[13] Faropenem had a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity against lower respiratory tract pathogens such as S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis,[16,33] with S. pneumoniae being the most susceptible. Two in vitro studies showed activity of faropenem (MIC90 0.25 and 1 µg/mL) against S. pneumoniae strains isolated from adults and children compared to quinolones and cephalosporins.[9,31] The activity of faropenem (MIC90 0.5 and 1 µg/mL) was comparable to coamoxiclav (MIC90 0.25 and 0.5 µg/mL) against H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis isolated from the lower respiratory tract.[16] These findings suggest the potential of faropenem against a variety of community pathogens, suggesting its effectiveness in treating community-acquired infections, especially respiratory tract infections.

The irrational use of antibiotics significantly contributes to antimicrobial resistance, the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria, delayed antimicrobial response, and even therapeutic failures.[21,22] Faropenem possesses unique characteristics that make it resistant to hydrolysis by nearly all β-lactamases.[40] In vitro studies (n=12) identified in this review showed the activity of faropenem with other antimicrobial agents such as β-lactams, quinolones, and cephalosporins against penicillin-resistant, β-lactamase– positive, and amoxicillin- or oxacillin-resistant strains. Critchley et al. reported that faropenem is less active against penicillin-intermediate resistant and S. pneumoniae-resistant strains compared to susceptible strains.[29] However, it was demonstrated that the activity of faropenem is not compromised against β-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis strains.[10,29] Furthermore, the MIC90 of faropenem was 0.015 µg/mL for penicillin-susceptible isolates of S. pneumoniae, while it was 1 µg/mL for penicillin-resistant strains, which was generally comparable to that of levofloxacin.[10] Milatovic et al. showed that the MICs of faropenem against β-lactamase positive and negative H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis strains were generally similar. The activity of faropenem against H. influenzae was comparable to that of co-amoxiclav, and its activity against M. catarrhalis was two- to eight-fold higher than that of cefpodoxime.[33] Furthermore, faropenem was demonstrated to have activity against methicillin- or oxacillin-resistant S. aureus.[14,15,33] These findings suggest that faropenem has activity against β-lactamase–producing bacterial isolates as well as penicillin-, methicillin-, and cloxacillin-resistant strains; however, comparative inference with other antibiotics is difficult due to variation in isolated strains, and methodology in studies.

This systematic review has several strengths. It is a comprehensive review of in vitro and comparative clinical trials demonstrating the activity of faropenem against a wide range of pathogens, including resistant strains. Furthermore, it compares the activity of faropenem with antibiotics of different classes, highlighting its clinical and microbiological efficacy. Several limitation s should also be noted. This review is limited to presenting the full-text articles published in the English language identified, through PubMed and Google Scholar, based on set PICOS inclusion criteria. We intended to understand how the therapeutic response obtained in comparative clinical trials of faropenem correlated with the in vitro activity of faropenem versus other antibiotics. However, a paucity of clinical comparative trials and the variation in in vitro studies of faropenem versus other antibiotics led to difficulties in making any definite inferences. In addition, we could not present the details of the risk of bias assessment for the clinical studies that were included since only a few studies met the inclusion criteria. There are limited in vitro studies reporting the activity of faropenem against azithromycin and levofloxacin.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review consolidates in vitro as well as clinical evidence of faropenem against a wide microbial spectrum. In in vitro studies, faropenem showed better antimicrobial activity compared to other antimicrobial agents such as co-amoxiclav, cefpodoxime, levofloxacin, and azithromycin against a wide spectrum of bacterial pathogens, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative aerobes and anaerobes, β-lactamase producers, and various resistant strains. Clinical studies demonstrated comparable clinical cure rates of faropenem compared to cefuroxime axetil in patients with acute bacterial sinusitis within 7 days of treatment. Furthermore, the findings underscore the potential for faropenem in treating community-acquired infections, particularly respiratory tract infections. However, more comparative clinical research is required for a definitive understanding of the antimicrobial activity and resistance pattern of faropenem compared to other antibiotics.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Roshni Patel, PhD and Sonali Dalwadi, PhD, CMPP™ of IWANA Consultancy Solutions for providing medical writing support for this manuscript.

Author contribution

DP and AS: Contributed to study concept, design, and methodology; AP and AS: Contributed to literature screening, analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to drafting and reviewing manuscript, and approved the final version to be published. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required

Declaration of patient consent

Patient consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

AP, DP, and AS are employees of Alkem Laboratories Ltd., Mumbai, India.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: This review was sponsored by Alkem Laboratories Ltd., Mumbai, India.

References

- Currently available antimicrobial agents and their potential for use as monotherapy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:30-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New antimicrobial molecules and new antibiotic strategies. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30:161-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol. 2018;4:482-501.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in pharmaceutical approaches of antimicrobial agents for selective delivery in various administration routes. Antibiotics. 2023;12:822.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role of faropenem in treatment of pediatric infections: The current state of knowledge. Cureus. 2022;14:e24453.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbapenem resistance: Overview of the problem and future perspectives. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2016;3:15-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://cdscoonline.gov.in/cdsco/drugs [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 24]

- Prevalence of serotype 19A Streptococcus pneumoniae among isolates from U.S. children in 2005-2006 and activity of faropenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2639-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Activity of faropenem against middle ear fluid pathogens from children with acute otitis media in Costa Rica and Israel. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2230-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro activity of β-lactams macrolides, telithromycin, and fluoroquinolones against clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Correlation between drug resistance and genetic characteristics. J Infect Chemother. 2005;11:262-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro evaluation of faropenem activity against anaerobic bacteria. J Chemother. 2005;17:36-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Activity of faropenem tested against Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates including fluoroquinolone-resistant strains. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53:311-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The in-vitro activity of faropenem, a novel oral penem. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;17:35-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative in vitro activity of furopenem against aerobic bacteria isolated from pediatric patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;22:301-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The in vitro effects of faropenem on lower respiratory tract pathogens isolated in the United Kingdom. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:581-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randomized double-blind study comparing 7-and 10-day regimens of faropenem medoxomil with a 10-day cefuroxime axetil regimen for treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:511-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the efficacy and safety of faropenem daloxate and cefuroxime axetil for the treatment of acute bacterial maxillary sinusitis in adults. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2003;260:186-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A systematic scoping review of faropenem and other oral penems: Treatment of Enterobacterales infections, development of resistance and cross-resistance to carbapenems. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2022;4:1-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections in adult primary care. JAMA. 2003;289:719-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral faropenem sodium-implications for antimicrobial resistance and treatment effectiveness. Indian Pediatr. 2022;59:879-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial multidrug resistance: Clinical implications for infection management in critically ill patients. Microorganisms. 2023;11:2575.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro activity of WY-49605, a penem antimicrobial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1995;5:251-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity of WY-49605 compared with those of six other oral agents and selection of disk content for disk diffusion susceptibility testing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1472-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro evaluation of the activity of beta-lactams, new quinolones, and other antimicrobial agents against Streptococcus pneumoniae. . 1996;2:213-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of faropenem, a new oral penem, against lower respiratory tract pathogens. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1999;5:282-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative in vitro activity of faropenem and 11 other antimicrobial agents against 405 aerobic and anaerobic pathogens isolated from skin and soft tissue infections from animal and human bites. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:411-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro activities of faropenem against 579 strains of anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3669-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Activities of faropenem, an oral β-lactam against recent U.S. isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:550-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faropenem, a new oral penem: Antibacterial activity against selected anaerobic and fastidious periodontal isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:721-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative in vitro activity of faropenem and 11 other antimicrobial agents against 250 invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates from France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:561-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro activity of faropenem and 20 other compounds against β-lactamase-positive and-negative Moraxella catarrhalis and Haemophilus influenzae isolates and the effect of serum on faropenem MICs. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:220-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro activity of faropenem against 5460 clinical bacterial isolates from Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:293-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Activity of WY-49605 compared with those of amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, imipenem, ciprofloxacin, cefaclor, cefpodoxime, cefuroxime, clindamycin, and metronidazole against 384 anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2599-604.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative antimicrobial activities of the penem WY-49605 (SUN5555) against recent clinical isolates from five U.S. Medical Centers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1591-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cefuroxime axetil. A review of its antibacterial activity pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1996;52:125-58.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro capability of faropenem to select for resistant mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:748-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The minimum inhibitory concentration of antibiotics: Methods, interpretation, clinical relevance. Pathogens. 2021;10:165.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- When and how to use MIC in clinical practice? Antibiotics. 2022;11:1748.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faropenem susceptibility of multidrug-resistant contemporary clinical isolates from Zhejiang Province, China. Infect Microbes Dis. 2020;2:26-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]