Translate this page into:

Hepatitis E virus: A leading cause of waterborne viral hepatitis in Northwest Districts of Punjab, India

Address for correspondence: Dr. Maninder Kaur, Department of Microbiology, Government Medical College, Amritsar, Punjab, India. E-mail: singhbunny1975@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Acute viral hepatitis (AVH) caused by enterically transmitted hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis E virus (HEV) poses a major health problem in developing countries such as India. Despite improving sanitation, heath awareness, and socioeconomic conditions, these infections continue to occur both in sporadic as well as in epidemic forms in different parts of India.

AIMS:

The aim of this study is to determine the total as well as age-specific prevalence rates of HAV and HEV in the outbreaks of waterborne hepatitis in districts surrounding Amritsar region of Punjab.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The study was conducted in the Virology Research and Diagnostic Laboratory, Government Medical College, Amritsar, during the study period of January 2015–March 2016. Samples from suspected outbreaks of AVH occurring in various districts around Amritsar were included as a part of the study. A total of 95 sera were tested for IgM antibody to HEV and HAV using IgM capture ELISA kit.

RESULTS:

Out of the total 95 samples received, 73 samples (76.84%) were positive for HAV/HEV. Out of the total positive cases, 65 (68.42%) had HEV infection, 2 (2.1%) had HAV, and 6 cases (6.31%) were coinfected with both HAV and HEV. The 21–30 years age group (25 cases) was identified as the most susceptible group for HEV infection. The coinfected subjects presented a wider range of age distribution (1–10 years: 1; 11–20 years: 3; 21–30 years: 1; 31–40 years: 1). Seasonal distribution of data revealed bimodal peaks for HEV infection.

CONCLUSION:

There should be some surveillance system to regularly monitor the portability of drinking water from time to time to avoid such preventable outbreaks in future.

Keywords

Acute viral hepatitis

hepatitis A virus

hepatitis E virus

outbreaks

Introduction

Acute viral hepatitis (AVH) caused by enterically transmitted hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis E virus (HEV) poses a major health problem in developing countries such as India. Both viruses are transmitted primarily by the fecal–oral route and cause a disease that is insignificant without serological testing.[1] India is hyperendemic for HAV and HEV.[2] Despite improving sanitation, heath awareness, and socioeconomic conditions, these infections continue to occur both in sporadic as well as in epidemic forms in different parts of India.

HAV is the most common cause of acute hepatitis in pediatric age group (1–3 years).[3] With improvement in socioeconomic conditions and its consequences, early childhood exposure to the virus has decreased. Hence, there has been a gradual shift in the age of acquiring the infection from early childhood to adulthood in different parts of the world.[4] HAV remains self-limiting and does not progress to chronic liver disease. Children with HAV tend to present with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms, and jaundice with cholestasis is common. Viral HAV in adults has more severe course than in children.[56]

HEV is one of the leading causes of hepatitis worldwide. Most of the outbreaks of waterborne hepatitis in India have been attributed to HEV.[7] It is uncommon in children younger than 10 years.[8] HEV affects young to middle-aged adults and causes high mortality in pregnant women, 20–30% as compared to 0.2–1% in general population.[9] HEV infection during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of prematurity, abortion, low birth weight, perinatal mortality, fulminant hepatitis, and maternal mortality.[8] HEV has been implicated as an important etiological agent for sporadic fulminant hepatic failure in developing countries.[8] Increasing the complexity of the HEV epidemiology, HEV is occasionally associated with HAV outbreaks in developing regions in the form of dual infection.[810]

According to the annual report of Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme, Punjab, a total of 19 outbreaks of hepatitis occurred from 2012 to 2014, out of which 6 outbreaks occurred in 2014 itself.[11] As limited data are available focusing on outbreaks of viral hepatitis in this region of Punjab, the present study was undertaken to investigate the contribution of HEV and HAV among cases of waterborne hepatitis and to study their epidemiology in relation to age and seasonal prevalence of these infections in this region.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in the Virology Research and Diagnostic Laboratory, Government Medical College (GMC), Amritsar, during the study period of January 2015–March 2016.

Serum samples from suspected cases of AVH were collected at the district level and sent through civil surgeon of respective districts to our tertiary care hospital at GMC, Amritsar, for investigating the causative organism behind the outbreaks. Each sample was accompanied by fully filled requisite form containing information regarding the name, age, sex, residential address, symptoms of AVH such as jaundice, fever, malaise, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, date of onset of symptoms, and date of sample collection.

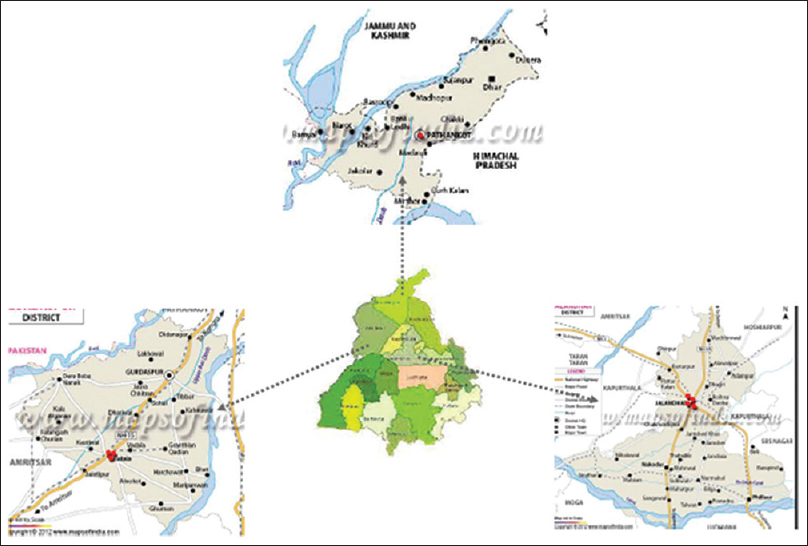

A total of nine outbreaks were reported, out of which four outbreaks were from Gurdaspur region, four from Jalandhar, and one from Pathankot [Figure 1]. All such samples received were included as a part of the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of Institutional Ethical Committee. All the sera were screened for IgM antibody to HEV and HAV using IgM capture ELISA kit (Dia. Pro Diagnostic Bioprobes, Italy) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Each test run was accompanied with two negative and one positive control provided within the kit as an internal quality check (according to the manufacturer, the kit has diagnostic sensitivity of 100% and diagnostic specificity of ≥95%).

- Map of Punjab showing hepatitis affected districts

Results

The present study, conducted to identify HAV and HEV in Punjab, reported nine outbreaks comprising a total of 95 samples. IgM antibodies for HAV/HEV were diagnosed in the serum samples of 73 cases (76.84%). Out of these, 65 (68.42%) were tested positive for HEV infection, 2 (2.1%) had HAV, and 6 (6.31%) were coinfected with both HAV and HEV.

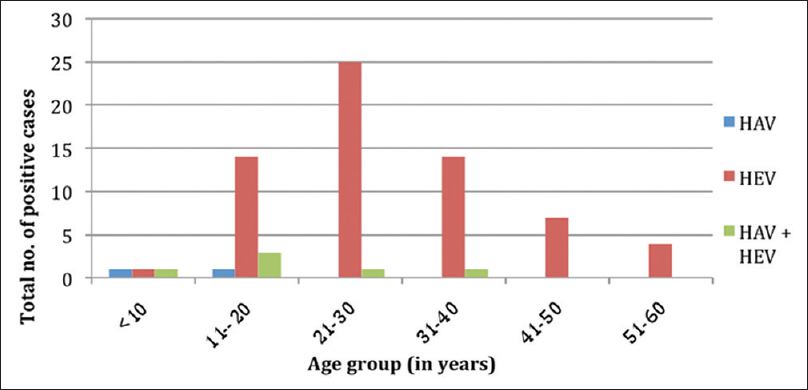

The cases were classified according to their age groups into ≤10 years, 11–20 years, 21–30 years, 31–40 years, 41–50 years, and >50 years [Figure 2]. The 21–30 years age group (25 cases) was identified as the most susceptible group for HEV infection. The HAV predominated in younger age groups (one case in ≤10 years and one in 11–20 years age group). The coinfected subjects presented a wider range of age distribution (1–10 years: 1; 11–20 years: 3; 21–30 years: 1; 31–40 years: 1) No major differences were reported in clinical presentations and outcome among the various age groups of coinfected cases.

- Age-wise distribution of positive cases of hepatitis A virus and hepatitis E virus

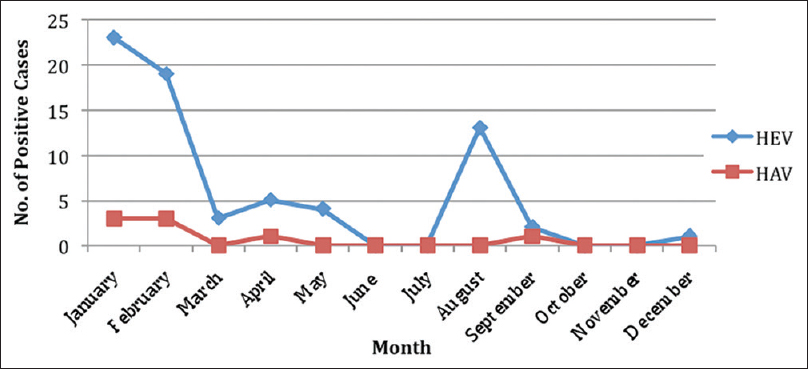

Seasonal distribution of data revealed bimodal peaks for HEV infection. One peak has been observed in winters and another peak in the monsoon season for both the infections [Figure 3].

- Seasonal distributions of positive cases of hepatitis A virus and hepatitis E virus

Discussion

HEV has been reported as a major causative agent in outbreaks reported from different parts of India in the past such as Kanpur,[7] Rajasthan,[12] Kolkata,[13] Hyderabad,[14] and Ahmedabad.[15] The present study also points toward HEV being the prime etiological agent for outbreaks of acute hepatitis in the studied region of Punjab.

A very high prevalence (68.42%) of HEV has been recorded in the current study. Similar figures were reported from other studies also.[161718] However, the prevalence observed for HAV was quite low (2.1%) indicating that HAV was also circulating. However, no significant difference has been seen in clinical presentation among HAV and HEV cases. Several studies from India and abroad have reported a varying prevalence of HAV ranging from 1.7% to 67%.[19] A comparatively lower HAV prevalence may be the consequence of an overall declining trend due to improved living standards and environmental hygiene. Besides, dual infections of HAV and HEV have also been detected in 6.31% cases, which is comparable to other studies undertaken in the Indian population.[1617]

Relatively higher number of adults in the age group of 21–30 years were infected with HEV in comparison to children (<20 years). This trend is a hallmark of HEV epidemiology and has been reported by other Indian authors too.[917] With the improvement in socioeconomic conditions and its consequences, early childhood exposure to HAV has decreased markedly. Hence, there has been a gradual shift in the age of acquiring the infection from childhood to adulthood in different parts of the world.[4] This trend has also been reported in this study as a single case of HAV has been seen in <10 years age group among the total HAV cases. In addition, out of the total coinfected (HAV and HEV) cases also, only one case was identified below 10 years.

Many authors have investigated fetal outcomes of HEV infection in pregnant women and found in utero transmission with fetal outcomes ranging from intrauterine fetal death to symptomatic and asymptomatic neonatal liver infection.[920] Interestingly, two pregnant females presented with the clinical symptoms for viral hepatitis and both of them were confirmed to contain the HEV IgM antibodies in their serum. On follow-up, one pregnancy ended in stillbirth and the other continued unaffected.

In reference to the seasonal variation of the occurrence of HAV and HEV infections, maximum number were diagnosed in winter months of January and February, followed by monsoons (August). Fecal contamination of water pipelines leading to contamination of drinking water may have been the reason for outbreaks in winter months. The heavy run off during rains causes contamination of water leading to excess of HAV and HEV infections during the rainy season. Outbreaks during rainy season have been reported by other researchers also.[2122]

Conclusion

These investigations are an indication to civic authorities to take prompt action to curtail the outbreaks. Collaboration of various public heath sectors to work together with health department for prevention of such outbreak is the need of the hour to avoid such kind of outbreaks in future.

Limitation of the study

The present investigation suffers from limitation that we received samples for investigating the type of virus causing the outbreaks and the reports of the results were sent to the respective civil surgeons of the various districts, but further actions such as locating the source and taking control measures necessary for curtailing the outbreaks were done at the level of district authorities.

Although the sample size is very less, high prevalence of HEV seen in outbreaks reported in the study region mandates the screening for HEV. This is especially essential for pregnant women where outcome can be affected besides mortality in pregnant females themselves.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Financial support was provided by the Secretary, Department of Health Research Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and the Director-General, ICMR, under Viral Research and Diagnostic Laboratory project.

References

- Hepatitis A and E seroprevalence and associated risk factors: A community-based cross-sectional survey in rural Amazonia. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:458.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroepidemiology of hepatitis A virus infection among school children in Delhi and North Indian patients with chronic liver disease: Implications for HAV vaccination. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:822-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of acute viral hepatitis in Southern India. Med J Armed Forces India. 2009;65:7-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological transition of hepatitis a in India: Issues for vaccination in developing countries. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128:699-704.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute hepatitis a infection in children: A 20-year experience of a medical center in Southern Taiwan. Acta Paediatr Taiwan. 2007;48:131-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A relapsing and protracted form of viral hepatitis A: Comparison of adults and children. Vnitr Lek. 1995;41:525-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- A large waterborne viral hepatitis E epidemic in Kanpur, India. Bull World Health Organ. 1992;70:597-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mystery of hepatitis e virus: Recent advances in its diagnosis and management. Int J Hepatol. 2015;2015:872431.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contribution of hepatitis E virus in acute sporadic hepatitis in north western India. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136:477-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transmission, diagnosis, and management of hepatitis E: An update. Hepat Med. 2014;6:45-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- An outbreak of viral hepatitis in Jodhpur city of Rajasthan. J Commun Dis. 1995;27:175-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- An outbreak investigation of viral hepatitis E in South dumdum municipality of Kolkata. India J Community Med. 2007;32:84-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of waterborne hepatitis E in Hyderabad, India, 2005. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:234-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemic investigation of the jaundice outbreak in Girdharnagar, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India, 2008. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:294-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of acute viral hepatitis due to hepatitis E virus in Hyderabad. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:378-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Water borne hepatitis a and hepatitis e in Malwa region of Punjab, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2163-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- An outbreak of hepatitis E virus in Raipur, Chattisgarh, India in 2014: A conventional and genetic analysis. J Med Microbiol Diagn. 2015;4:209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus and hepatitis E virus as causes of acute viral hepatitis in North India: A hospital based study. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:261-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis E virus (HEV) in the patients presenting with acute viral hepatitis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33:102-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of an epidemic of non-A, non-B hepatitis. Possibility of another human hepatitis virus distinct from post-transfusion non-A, non-B type. Am J Med. 1980;68:818-24.

- [Google Scholar]