Translate this page into:

Pulmonary nocardiosis caused by Nocardia arthritidis – A case report

*Corresponding author: Latha Ragunathan, Department of Microbiology, Aarupadai Veedu Medical College and Hospital, Puducherry, India. latha.ragunathan@avmc.edu.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Shebeena S, Haridas C, Ragunathan L, Raj M, Kannaiyan K, Balaji K, et al. Pulmonary nocardiosis caused by Nocardia arthritidis – A case report. J Lab Physicians. 2024;16:417-21. doi: 10.25259/JLP_64_2024

Abstract

Nocardiosis is a rare systemic infection caused by aerobic, Gram-positive filamentous bacteria that belong to the genus Nocardia, typically affecting immunocompromised individuals but can also manifest in immunocompetent people. We report a case of pulmonary nocardiosis caused by Nocardia arthritidis in a 56-year-old female with a history of recurrent respiratory illness. The patient presented with a persistent cough, on-and-off fever, and a history of pulmonary tuberculosis. Sputum analysis revealed Gram-positive beaded branching filamentous bacilli, confirmed as N. arthritidis through molecular methods. Treatment with cotrimoxazole and ceftriaxone led to symptomatic improvement.

Keywords

Pulmonary nocardiosis

Nocardia arthritidis

Immunocompetent

INTRODUCTION

Edmond Nocard, a French microbiologist, was the pioneer in describing Nocardial infections. Nocardia spp. is slender, Gram-positive, beaded, branching, and filamentous bacilli that grow slowly in aerobic conditions. They show weak acid-fast staining properties and are typically found in soil.[1] It primarily affects immunocompromised individuals but can also occur in one-third of cases in people with normal immune function.[2] In immunocompromised individuals, pulmonary nocardiosis is more prevalent than extrapulmonary cases, primarily affecting the skin and soft tissues, presenting as cellulitis, mycetoma, and lymphocutaneous lesions resembling sporotrichosis.[3] Nocardiosis presents a broad spectrum of clinical symptoms, including cutaneous infections and the involvement of the pulmonary and central nervous systems. Here, we report a rare case of pulmonary nocardiosis in an immunocompetent patient caused by Nocardia arthritidis.

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old female presented to the respiratory medicine outpatient department with complaints of cough with expectoration and loss of weight for three months. Cough was chronic, productive, and more at night which aggravated on lying in the left lateral position. Sputum was yellow colored, mucopurulent, and more at night aggravating on lying in the left lateral position.

The patient had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis seven years back, for which she completed antituberculosis therapy for six months. She had a recurrent respiratory illness for one and a half years and had been taking treatment from other hospitals without complete relief of symptoms. History of COVID-19, one year back, she took the COVID-19 vaccine. She took multiple courses of antibiotics, but the symptoms persisted. She had no other relevant history.

On the first day, a detailed physical and respiratory system examination was done. All the routine investigations were sent, including sputum AFB and culture and sensitivity. The general examination findings were normal. Examination of the respiratory system showed normal vesicular breath sounds with bilateral air entry with coarse crepitations in the right mammary and bilateral basal areas on auscultation. Chest X-ray PA view showed cystic areas in the right middle zone, right lower zone, and left lower zone [Figure 1]. All blood investigations were normal except for the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which was elevated.

- Chest X-ray showing cystic areas in the right middle zone, right lower zone, and left lower zone.

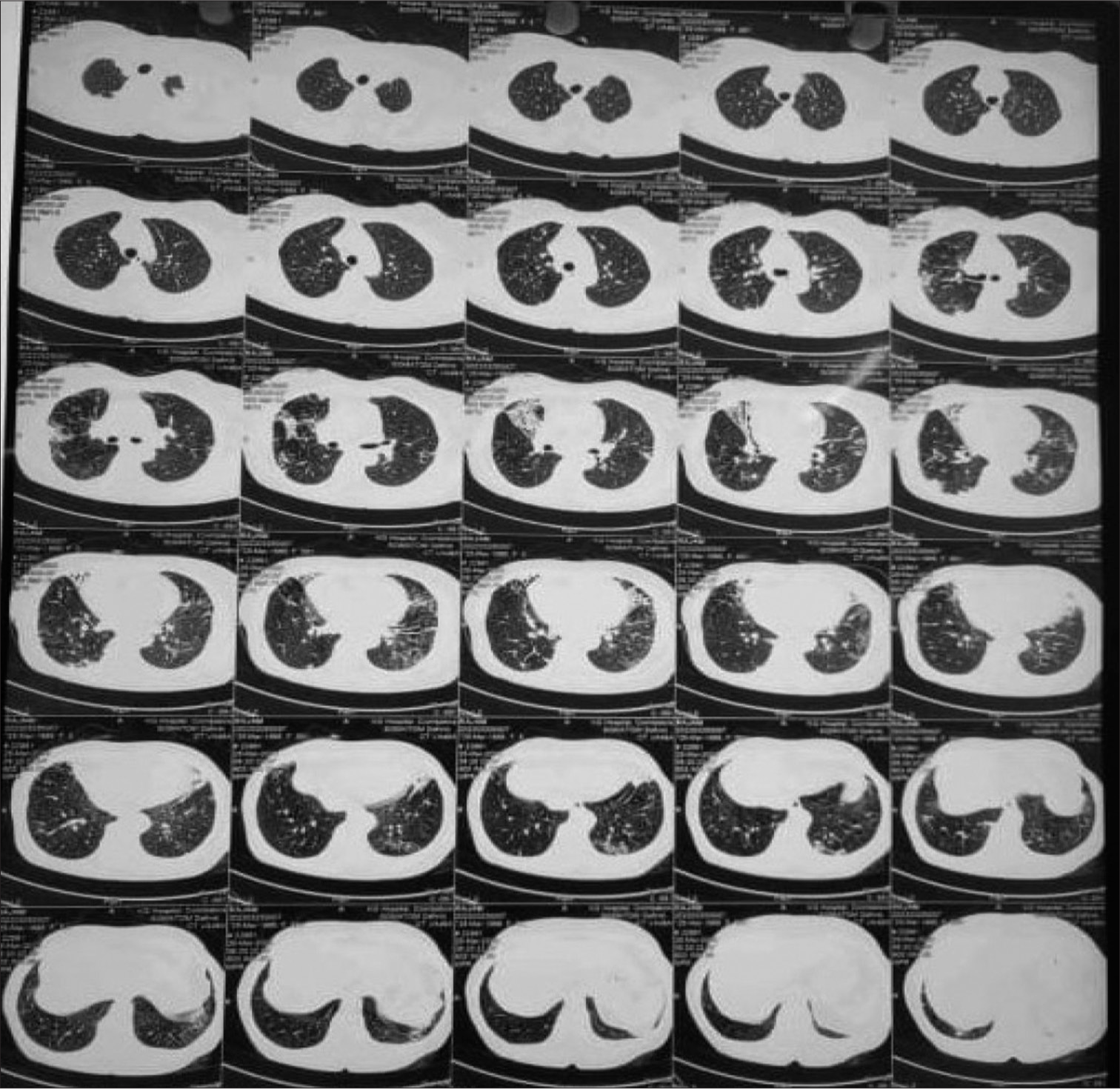

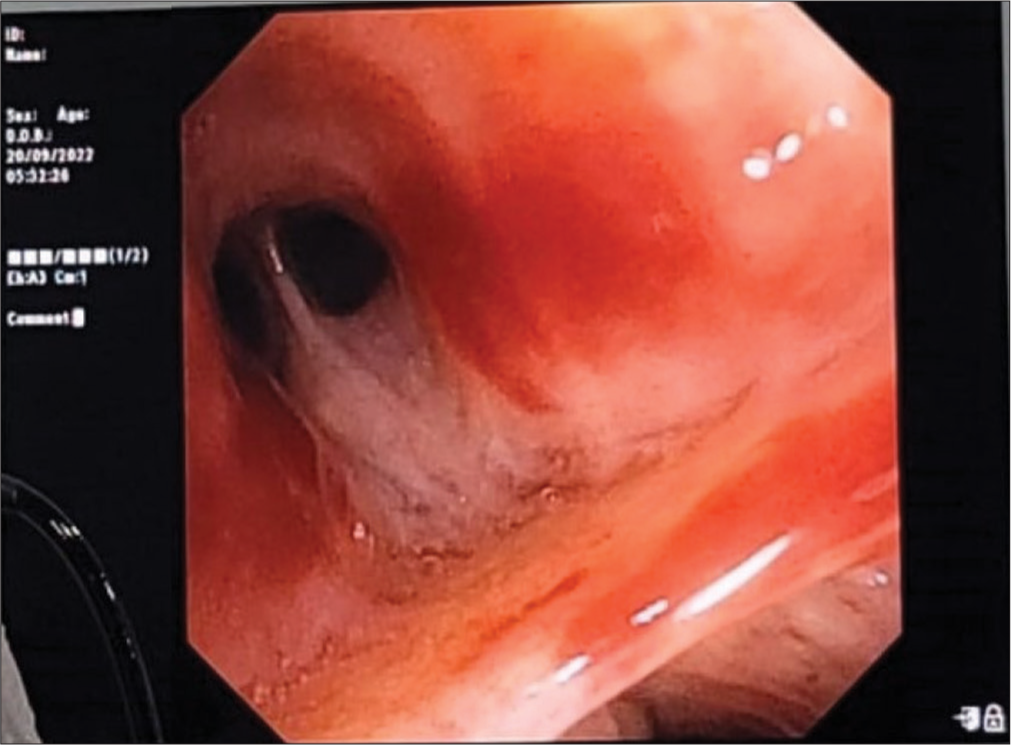

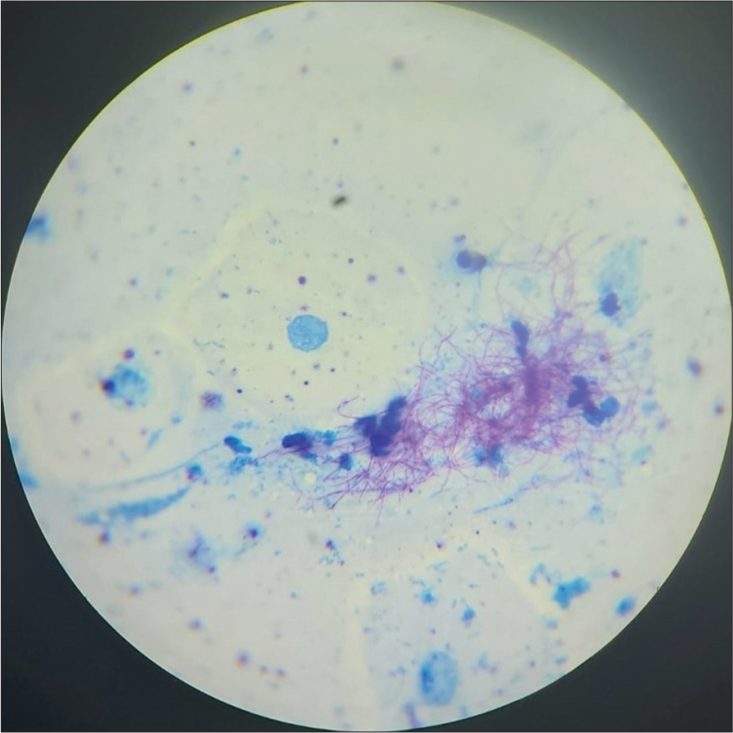

Sputum was sent for gram stain, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining, culture, and sensitivity. High-resolution computed tomography thorax was also done as the X-ray showed cystic changes and showed bilateral apical pleural thickening with bilateral lung hyperinflation, right middle lobe and left lower lobe bronchiectasis (tubular), bilateral lower lobe mucoid impaction, and bilateral lower lobe patchy consolidation [Figure 2]. Sputum Grams stain showed plenty of pus cells with few Gram-negative bacilli. AFB staining showed no AFB. Sputum culture and sensitivity showed growth of Klebsiella spp. sensitive to amikacin, amoxiclav, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, piperacillin/tazobactam, ciprofloxacin, co-trimoxazole, gentamycin, and meropenem. The patient was given ceftriaxone 1 gm intravenously twice daily according to antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) for Klebsiella sp., but the patient was not symptomatically improving. Hence, a bronchoscopy was performed to rule out tuberculosis and fungal pathology. Both tracheobronchial trees left lower lobe bronchial segments, right middle lobe, and right lower lobe segments were widely dilated and mucopurulent secretion was present [Figure 3]. Bronchoalveolar lavage from the right middle lobe and right and left lower lobe was sent for gram stain, AFB staining, and culture and sensitivity. Gram stain showed pus cells and gram variable branching filamentous bacilli; hence, a modified Ziehl–Neelsen staining using 1% H2SO4 was done. It was positive for Nocardia spp. [Figure 4]. Chalky white, tough colonies with a freshly turned soil odor were grown in blood agar after 48 h [Figure 5]. Subculture on brain heart infusion agar showed dry, chalky white, tough, and glabrous colonies. Antibiotic susceptibility testing for Nocardia was done by the minimum inhibitory concentration broth dilution method using cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines M24 3rd edition. The isolate was found susceptible to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, amikacin, gentamycin, cotrimoxazole, ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, cefepime, ceftazidime, doxycycline, linezolid, and resistant to imipenem. Serum immunoglobulin (Ig) profile of the patient was done (Serum IgA 290 mg/dL, serum IgM 150 mg/dL, and Ig G 850 mg/dL) to rule out immunosuppression.

- High-resolution computed tomography thorax showing bilateral apical pleural thickening with the right middle and left lower lobe bronchiectasis.

- Bronchoscopy image showing thick mucopurulent secretion in the right middle lobe medial segment.

- Modified Ziehl Neelsen staining showing acid-fast branching filamentous bacilli.

- Chalky white, tough colonies grown in blood agar.

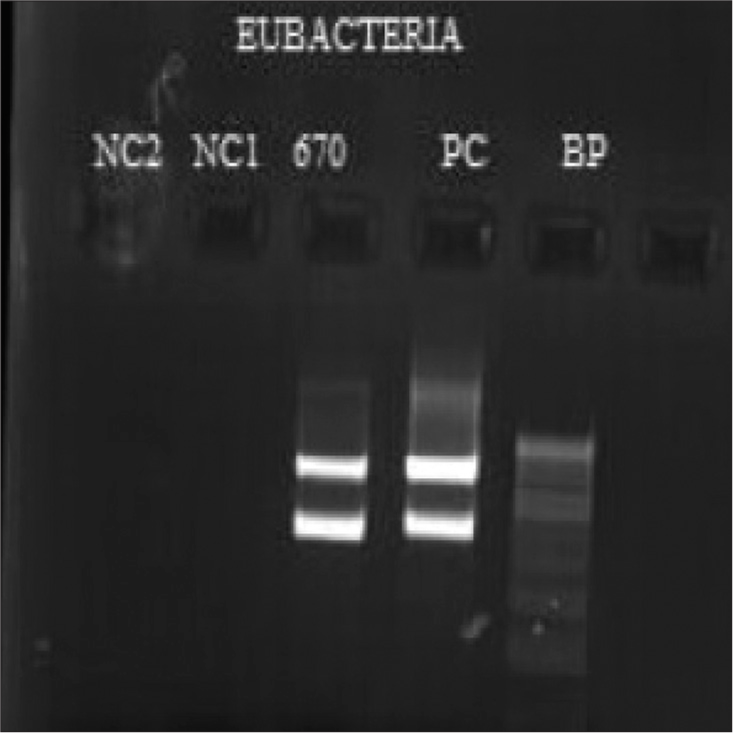

The isolate was speciated using molecular techniques. DNA was extracted from the isolate and subjected to polymerase chain reaction. Gel electrophoresis was performed to confirm the presence of the bacterial genome, targeting the 16s ribosomal RNA region [Figure 6]. Sanger sequencing confirmed it as N. arthritidis.

The patient was treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX 160mg/800mg) TID and other supportive therapy for one week. The patient clinically improved and was continued on TMP/SMX for six months. She was on regular follow-up. The sputum culture and sensitivity showed no growth of Nocardia after six months.

- Gel electrophoresis image of the amplicon of bacterial genome targeting 16S ribosomal RNA region.

DISCUSSION

Nocardia spp. is often considered an opportunistic pathogen causing infection in people with immunosuppression. A combination of long-term corticosteroid therapy, chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, elderly people, and diabetes mellitus are some of the risk factors. The most common site of infection is the lungs.[4] A study conducted by Wang et al. in China stated that specimens from the respiratory tract, skin, and soft-tissue infections accounted for a larger percentage in their study. Nocardia species have different geographic prevalence, with Nocardia farcinica, Nocardia cyriacigeorgica, and Nocardia abscessus identified as most common in some studies and Nocardia cyriacigeorgica and Nocardia nova complex in other studies conducted in different geographical areas.[5] N. arthritidis are strictly aerobic, Gram variable, AFB, first isolated from the sputum and exudate of a rheumatoid arthritis patient in 2004.[6] However, the first isolate was obtained from animals infected with bovine farcy, a granulomatous disease, by Edmond Nocard in the year 1888 on Guadeloupe Island.[7] Here, we report a rare case of an immunocompetent patient with pulmonary nocardiosis caused by N. arthritidis. Accurately diagnosing nocardiosis is crucial for determining the appropriate treatment. The definitive diagnosis typically relies on isolating microorganisms from clinical samples. However, conventional culture methods often struggle to isolate these microorganisms due to their slow growth, and they may be overshadowed by the rapid growth of other aerobic bacteria in mixed flora. Hence, the incubation period of microbiological samples is to be extended 2–3 weeks to facilitate the growth of Nocardia, if suspected, given its prolonged incubation period.[8]

Another challenge is performing AST for Nocardia, as there are insufficient data correlating AST and clinical outcomes. According to the CLSI guidelines, micro-broth dilution with cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth is the standard reference for Nocardia.[9] The treatment of choice is TMP-SMX for the long term, and it is used in immunocompromised people for prophylactic treatment of Nocardia and Pneumocystis jirovecii.[10] In this case, the patient was given TMP/SMX for 6 months; the patient recovered completely with no relapse.

CONCLUSIONS

Nocardia are ubiquitous saprophytes in soil, dust, decaying vegetation, and animal fecal deposits worldwide. It is an aerobic, Gram-variable, and acid-fast actinomycete that forms branched orange substrate mycelium. Pulmonary nocardiosis resulting from N. arthritidis is scarcely documented, but its incidence is increasing due to population longevity and comorbidities. Clinical suspicion is vital because specific tests and extended treatment are necessary for identification and management.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Nocardiosis: A neglected disease. Med Princ Pract. 2020;29:514-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary nocardiosis. A case report. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2022;35(Suppl 1):114-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical manifestations and outcome of nocardiosis and antimicrobial susceptibility of Nocardia species in southern Taiwan, 2011-2021. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2023;56:382-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revisiting nocardiosis at a tertiary care institution: Any change in recent years? Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:446-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance profiles of the Nocardia species in China, 2009 to 2021. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10:e0156021.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocardia arthritidis scleritis: A case report. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2023;29:101794.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocardiosis with diffuse involvement of the pleura: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:6824-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic susceptibility testing and species identification of Nocardia isolates: A retrospective analysis of data from a French expert laboratory, 2010-2015. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:489-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenic Nocardia A diverse genus of emerging pathogens or just poorly recognized? PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008280.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]