Translate this page into:

Revisiting renal amyloidosis with clinicopathological characteristics, grading, and scoring: A single-institutional experience

Address for correspondence: Dr. Megha S. Uppin, Department of Pathology, Nizam's Institute of Medical Sciences, Punjagutta, Hyderabad - 500 082, Telangana, India. E-mail: megha_harke@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Kidney involvement is a major cause of mortality in systemic amyloidosis. Glomerulus is the most common site of deposition in renal amyloidosis, and nephrotic syndrome is the most common presentation. Distinction between AA and AL is done using immunofluorescence (IF) and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Renal biopsy helps in diagnosis and also predicting the clinical course by applying scoring and grading to the biopsy findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The study includes all cases of biopsy-proven renal amyloidosis from January 2008 to May 2017. Light microscopic analysis; Congo red with polarization; IF; IHC for Amyloid A, kappa, and lambda; and bone marrow evaluation were done. Classification of glomerular amyloid deposition and scoring and grading are done as per the guidelines of Sen S et al.

RESULTS:

There are 40 cases of biopsy-proven renal amyloidosis with 12 primary and 23 secondary cases. Mean age at presentation was 42.5 years. Edema was the most common presenting feature. Secondary amyloidosis cases were predominant. Tuberculosis was the most common secondary cause. Multiple myeloma was detected in four primary cases. Grading of renal biopsy features showed a good correlation with the class of glomerular involvement.

CONCLUSION:

Clinical history, IF, and IHC are essential in amyloid typing. Grading helps provide a subtle guide regarding the severity of disease in the background of a wide range of morphological features and biochemical values. Typing of amyloid is also essential for choosing the appropriate treatment.

Keywords

Grading

immunofluorescence

immunohistochemistry

renal amyloidosis

typing of amyloid

Introduction

Amyloidosis encompasses a group of diseases characterized by tissue deposition of abnormal proteins in the form of insoluble fibrils which have characteristic appearance on light microscopy, electron microscopy, and X-ray diffraction studies.[12] The fibrils are heterogeneous in chemical composition; Amyloid Light chain and AA are the most common, seen in primary amyloidosis or myeloma and chronic inflammatory conditions, respectively.[2345] Others include Amyloid transthyretin in senile systemic amyloidosis and hereditary polyneuropathies and AB2 in long-term hemodialysis.[23456] Based on the extent of involvement, it is classified into localized and systemic forms. Most cases of hereditary amyloidosis are associated with hereditary inflammatory diseases such as familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) and Muckle–Wells syndrome.[7] Morbidity in amyloidosis is related to the direct toxicity of the amyloid fibrils as well as to the extent of functional compromise of the involved organ.[89]

The kidney is one of the most common organs to be affected in systemic amyloidosis, which is also a principal cause of mortality other than the heart, irrespective of the underlying cause.[10] The spectrum of renal morphological changes is quite variable, with the chemical composition determining the predominant site of involvement to a certain extent.[1112] Nevertheless, glomerulus is the most common site of initial fibril deposition. Other associated findings such as glomerular sclerosis, interstitial inflammation, fibrosis, and tubular atrophy also contribute to the morbidity significantly.[1314]

The most common presentation of renal amyloidosis is nephrotic syndrome; however, patients can present with renal failure if the deposits are predominantly vascular or medullary. It leads to end-stage renal disease if left untreated. Hypertension is less common, and diabetes insipidus has been reported uncommonly.[1516]

Histopathology forms the cornerstone for diagnosis using Congo red staining and visualization under a polarizing microscope where it displays apple-green birefringence.[17] Tests for categorizing into primary and secondary include demonstration of clonality of light chains using immunofluorescence (IF) or immunohistochemistry (IHC) in the former and of acute-phase reactants, usually Serum Amyloid A (SAA), in the latter.[181920] Renal biopsy is a valuable tool for diagnosis as well as predicting the clinical course.

Scoring of renal amyloid deposits has been attempted in several studies.[21222324] However, the scoring and grading scheme proposed by Sen S et al. provides a better means for predicting the outcomes as well as comparing therapeutic trials.[11] They have also attempted to standardize reporting of renal amyloidosis which enables uniformity and interinstitutional comparison.

The type of renal amyloidosis also has shown geographic variations. The western world has shown the dominance of primary or light-chain forms, whereas secondary form is common in the developing countries including India.[25262728]

In this article, we have tried to study the clinical features, biopsy findings, as well as grading of amyloid on renal biopsies.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective study and included all cases of biopsy-proven renal amyloidosis from January 2008 to May 2017. The clinical information was retrieved from medical records, and the clinical and demographic features were noted with respect to age and other demographic details, clinical presentation, proteinuria, renal failure, and bone marrow biopsy details.

Histopathological analysis

Light microscopic evaluation was done with the help of hematoxylin and eosin (H and E), periodic acid–Schiff, methenamine silver–periodic acid–Schiff, Masson's trichrome, and Congo red with polarization. In all the cases, amyloid was visualized as amorphous eosinophilic extracellular material on H and E which was congophilic and showed apple-green birefringence under polarizer.

Direct IF was performed on fresh-frozen renal biopsy using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibodies against kappa and lambda light chains along with IgM, IgA, IgG, C3, and C1q in 1:30 dilution followed by incubation for 30 min. The slides were examined under Zeiss Axioscope with FITC filter.

IHC was performed using ready-to-use antibodies against AA (Dako, Germany) and kappa and lambda light chains (Dako, Germany) on a fully automated immunostainer. Goat anti-rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin was used as a secondary antibody which was labeled using poly-horseradish peroxidase polymer, and 3,3'-diaminobenzidine was used as the chromogen.

The immunostaining, both IF and IHC, was interpreted in every case by comparing with positive and negative controls for kappa, lambda, and SAA. Tissues of documented cases were used as positive controls and tissues on which antibody addition was omitted were used as negative controls. Mesangial staining was taken into account for interpretation of light chains.

Histopathological evaluation

The amyloid deposits in biopsies were looked for dominant involvement, i.e. glomerular, interstitial, vascular, or all compartments.

The classification of glomerular involvement from 1 to 6 along with scoring and grading is done as per the study by Sen S et al.

Scoring of amyloid included the extent of involvement of glomerular, interstitial, and vascular compartments as well as interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, interstitial inflammation, and glomerular sclerosis in addition to the glomerular class, and the cumulative score is called the renal amyloid prognostic score (RAPS).[11] The renal findings are finally graded according to the RAPS into four grades from 0 to 3.

AL amyloidosis was confirmed by demonstrating:

-

Light-chain restriction using direct IF

-

Bone marrow plasma cells along with immunoelectrophoresis and immunofixation.

AA amyloidosis was considered by:

-

History of chronic infection

-

Absence of light-chain restriction

-

Positive IHC expression of AA.

Results

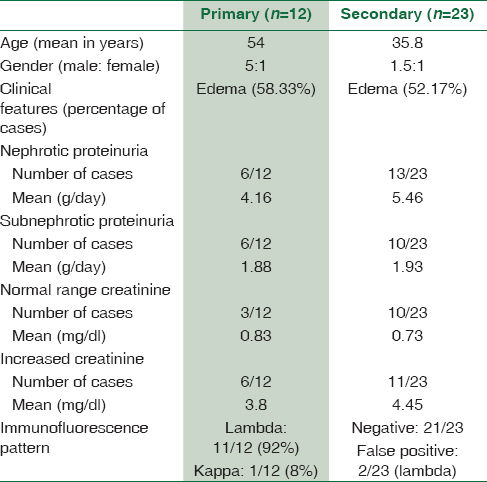

A total of 40 cases of renal amyloidosis were diagnosed in the study period including12 primary and 23 secondary cases. Five biopsies remained unclassified due to inadequate tissue for IHC and unavailability of complete clinical details. The 40 patients included 28 male and 12 females with an M: F ratio of 2.3:1. Edema was the most common presenting feature. Others included joint pains, diarrhea, and raised serum creatinine. Mean proteinuria was 3.8 g/24 h and mean creatinine 3.1 mg/dl.

A comparison of the basic clinical and laboratory parameters is provided in Table 1. Higher mean age and light-chain restriction was seen in primary amyloidosis. Two secondary amyloidosis cases also showed lambda light-chain restriction on IF. However, these two patients had a history of chronic infection and positive AA IHC on biopsy. The bone marrow examination did not reveal increased plasma cells.

Among the 12 cases of primary amyloidosis, four were subsequently diagnosed as multiple myeloma. The remaining eight cases did not fulfill the diagnostic criteria for myeloma and hence classified as nonmyeloma-associated primary amyloidosis. Light-chain restriction in these cases was found to be lambda type, with a single case showing kappa restriction.

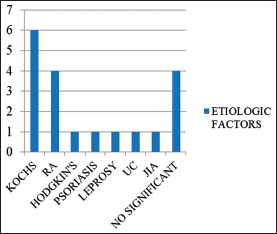

Tuberculosis was the most common chronic infection in the secondary amyloid cases (6/23) as shown in Graph 1.

- Spectrum of secondary causes of amyloidosis. RA=Rheumatoid arthritis; UC=Ulcerative colitis; JIA= Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

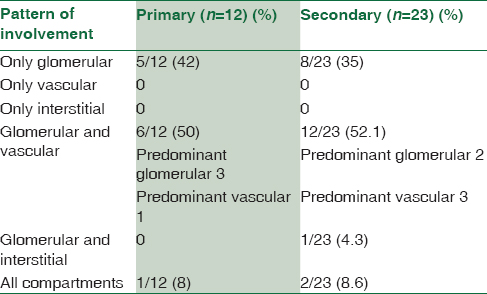

The histopathological findings are summarized in Table 2 and show predominant glomerular involvement in all the groups.

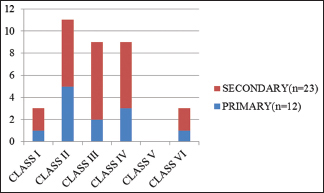

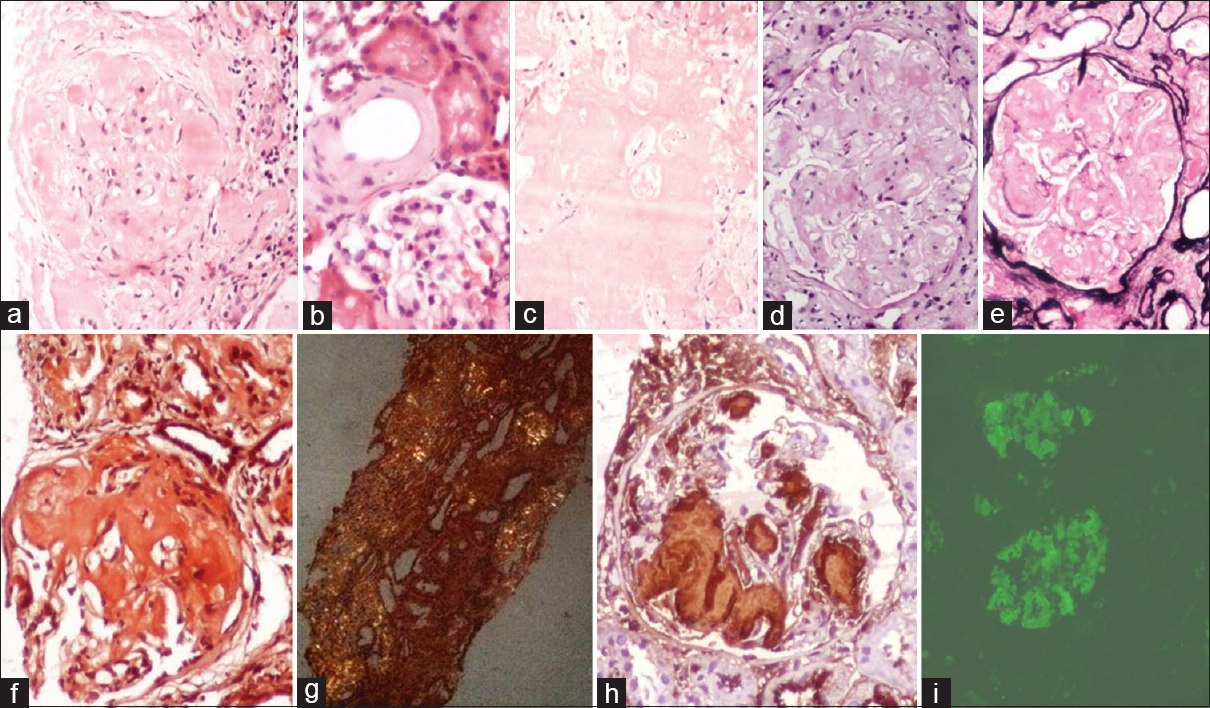

The classification of glomerular involvement is shown in Graph 2 and Figure 1.

- Classification of glomerular amyloid deposits shows cases predominantly in Class 2

- Glomerular (a), vascular (arrow) (b), and interstitial (c) amyloid deposits in H and E. These deposits are negative on periodic acid–Schiff (d) and methenamine silver-periodic acid–Schiff (e). Congo red staining shows positivity (f) with apple-green birefringence under polarizer (g). Immunohistochemistry with AA shows positivity in a case of secondary amyloidosis (h). Direct immunofluorescence showing lambda positivity in a primary amyloidosis case (i)

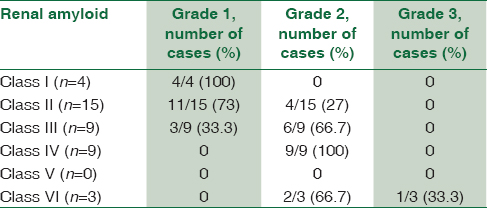

Grading of amyloidosis showed predominantly Grade 2 and correlated well with the class [Table 3] of glomerular involvement.

Discussion

We report 40 cases of biopsy-proven renal amyloidosis over a 9-year period, which accounted for 0.34% of all the renal biopsies in the study period. Majority (65.7%) of the cases were secondary in our series, similar to other Indian and some of the Asian studies. Contrarily, primary amyloidosis is more common in studies from the Western world.[252627] The mean age at presentation is variable, ranging from 35 to 63 years in different studies similar to that observed in the present study.[7252627282930] Primary amyloidosis is seen in the elderly age group. Chronic infections such as tuberculosis and leprosy are prevalent in India and other developing Asian countries, and this is perhaps the reason for more number of secondary amyloid cases. Renal involvement is the rule in secondary AA type of amyloidosis which is seen in younger individuals as against the primary amyloidosis.

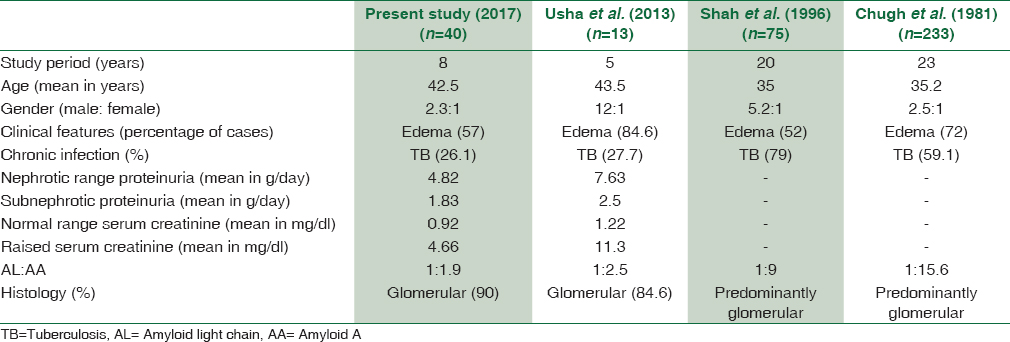

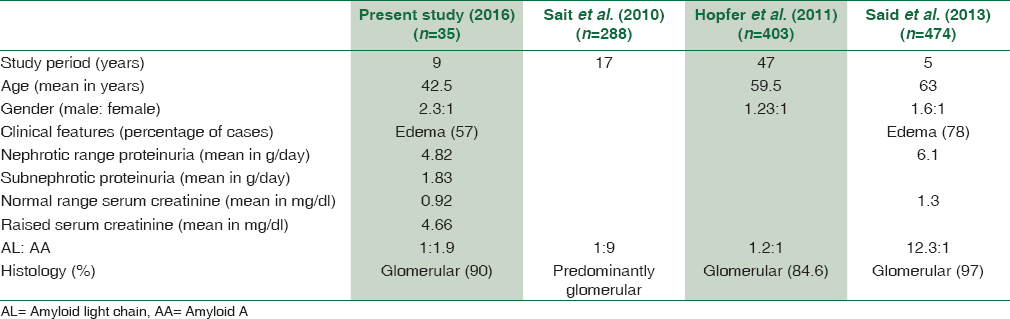

Majority of our patients had nephrotic range proteinuria with subnephrotic range in few. This finding is also comparable to other studies and can be explained by the predominance of glomerular involvement.[111226313233] A comparison of the findings of the present study with other similar studies is provided in Tables 4 and 5.

Some of the authors correlated the principal site of involvement in the renal biopsy with the type of precursor protein and showed that fibrinogen A alpha amyloidosis is typically glomerular and the deposits in AApoA and ALECT2 are extraglomerular and present with renal failure.[1112] The pattern of renal involvement in the present study was predominantly glomerular (90%), either in isolation or in addition to other compartments. Exclusive vascular or interstitial involvement was not seen in the absence of glomerular deposition. There were no differences between primary and secondary amyloidosis cases with respect to the distribution of amyloid in various compartments of the kidney. This is the reason why light microscopic findings alone are not sufficient to characterize the type of amyloid protein. Clinical history as well as IF and IHC is essential in the workup of amyloid subtyping.

We attempted to score and grade the amyloid as per the guidelines of Sen S et al.[11] Most of our cases belonged to Classes 2–4 and none belonged to Class 5. In their study, a positive correlation was noted between Class 1 and Grade 1, Class 3 and Grade 2, and Class 4 and Grade 3. Our findings were comparable to that of Sait et al. as has been given in Table 5. These findings help provide a subtle guide to the clinicians regarding the severity of the disease in the background of a wide range of morphological features and biochemical values. However, it needs a clinical follow-up of patients for comparison with the outcome and survival analysis. The findings of Sen S et al.[11] were predominantly based on AA type of precursor in cases of FMF which was the major cause of secondary amyloidosis in their study. Unlike that, the present study had a variety of underlying conditions, with tuberculosis being the major chronic infection. Our series does not include any heredofamilial cases. Nevertheless, the grading of renal biopsy showed a good correlation with the class of glomerular amyloid deposits and can be expected to give a good idea of overall prognosis.

Typing of amyloid is also essential for choosing the appropriate line of treatment. The current treatment strategies aim to eradicate the underlying source of clonal plasma cell population in AL amyloidosis. Chemotherapeutic drugs and autologous stem cell transplantation to help the recovery of the marrow have been employed for the same. On the other hand, the treatment for AA amyloidosis aims to halt the chronic inflammatory process by employing cytotoxic agents and tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Even with these agents, it may be difficult to suppress SAA production adequately. Molecules that inhibit fibrillogenesis are under trial for these cases.[8] Treatment-associated toxicity with chemotherapy remains an issue of concern. Hence, therapy needs to be administered only after the nature of amyloid is proved to be AL or AA by appropriate tests on the biopsy.

Retrospective nature of the study and absence of follow-up data are the limitations of the present study.

Conclusion

We have seen more number of secondary amyloidosis in patients having a history of varied chronic infectious and inflammatory diseases. The pattern of renal involvement does not vary with the type of amyloidosis. Grading and scoring the amyloid on renal biopsy correlates with the class of glomerular involvement.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amyloid deposits and amyloidosis. The beta-fibrilloses (first of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1980;302:1283-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amyloid fibril protein nomenclature: 2012 recommendations from the Nomenclature Committee of the International Society of Amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2012;19:167-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nomenclature 2014: Amyloid fibril proteins and clinical classification of the amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2014;21:221-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anew form of amyloid protein associated with chronic hemodialysis was identified as beta 2-microglobulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;129:701-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics of the patients with systemic amyloidosis in 2000-2010. Rev Clin Esp (Barc). 2013;213:186-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- AL-amyloidosis and light-chain deposition disease light chains induce divergent phenotypic transformations of human mesangial cells. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1322-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- A proposed histopathologic classification, scoring, and grading system for renal amyloidosis: Standardization of renal amyloid biopsy report. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:532-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal amyloidosis: Origin and clinicopathologic correlations of 474 recent cases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1515-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognosis of renal amyloidosis: A clinicopathological study using cluster analysis. Nephron. 2001;87:42-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and histological characteristics of renal AA amyloidosis: A retrospective study of 68 cases with a special interest to amyloid-associated inflammatory response. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1798-809.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus caused by amyloid disease. Evidence in man of the role of the collecting ducts in concentrating urine. Am J Med. 1960;29:539-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Persistent water diuresis in renal amyloidosis. A case report. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1981;15:77-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A short historical survey of developments in amyloid research. Protein Pept Lett. 2006;13:213-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunohistochemical classification of amyloid in surgical pathology revisited. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:673-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and immunohistochemical classification of systemic amyloidoses. Report of 43 cases in an unselected autopsy series. Virchows Arch. 1998;433:19-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunohistochemistry in the classification of systemic forms of amyloidosis: A systematic investigation of 117 patients. Blood. 2012;119:488-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphological and clinical features of renal amyloidosis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1975;366:125-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal amyloidosis. Correlations between morphology, chemical types of amyloid protein and clinical features. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1988;412:197-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perimembranous-type renal amyloidosis: A peculiar form of AL amyloidosis. Nephron. 1989;53:27-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glomerular crescents in renal amyloidosis: An epiphenomenon or distinct pathology? Pathol Int. 2001;51:179-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systemic amyloidosis in England: An epidemiological study. Br J Haematol. 2013;161:525-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal amyloidosis – A clinicopathologic study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:179-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Secondary systemic amyloidosis: Response and survival in 64 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:246-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical profile of patients having pulmonary tuberculosis and renal amyloidosis. Lung India. 2009;26:41-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- A retrospective analysis for aetiology and clinical findings of 287 secondary amyloidosis cases in Turkey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:2003-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal involvement in systemic amyloidosis – An Italian retrospective study on epidemiological and clinical data at diagnosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1608-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathological study of renal amyloidosis. Clinicopathological study of renal amyloidosis. JK Sci. 2006;8:18-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal amyloidosis revisited: Amyloid distribution, dynamics and biochemical type. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2877-84.

- [Google Scholar]