Translate this page into:

Spinal Tuberculosis (Pott's disease) Mimicking Paravertebral Malignant Tumor in a Child Presenting with Spinal Cord Compression

Address for correspondence: Professor. Suna Emir, sunaemir@yahoo.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Paravertebral tumors may interfere with the radiological and clinical features of spinal tuberculosis. We report a case of a 3-year-old boy with spinal tuberculosis who was initially misdiagnosed as having a paraspinal tumor. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was made on the basis of intraoperative findings and confirmed by histopathology. This case highlights the importance of awareness of the different radiographic features of spinal tuberculosis, which can mimic a spinal malignancy. In order to avoid delayed diagnosis, pediatricians and radiologists must be aware of spinal tuberculosis, which may interfere with other clinical conditions.

Keywords

Cancer

children

paravertebral tumor

pott's disease

tuberculosis

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (tbc) remains one of the most important infectious diseases and its incidence is increasing in Turkey and all over the world.[12] Tuberculosis of the skeletal system is frequently located in the spine, a condition known as, “Pott's disease”. It affects individuals of all ages, but mainly children.

If the possibility of spinal tuberculosis as a diagnosis is not initially kept in mind, radiological and clinical features might lead to misdiagnosis, as they can be indistinguishable from those of malignant lesions.

Here, we report a case of a 3-year-old boy with spinal tuberculosis that was initially misdiagnosed as a paraspinal tumor. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was made on the basis of intraoperative findings and confirmed by histopathology.

CASE REPORT

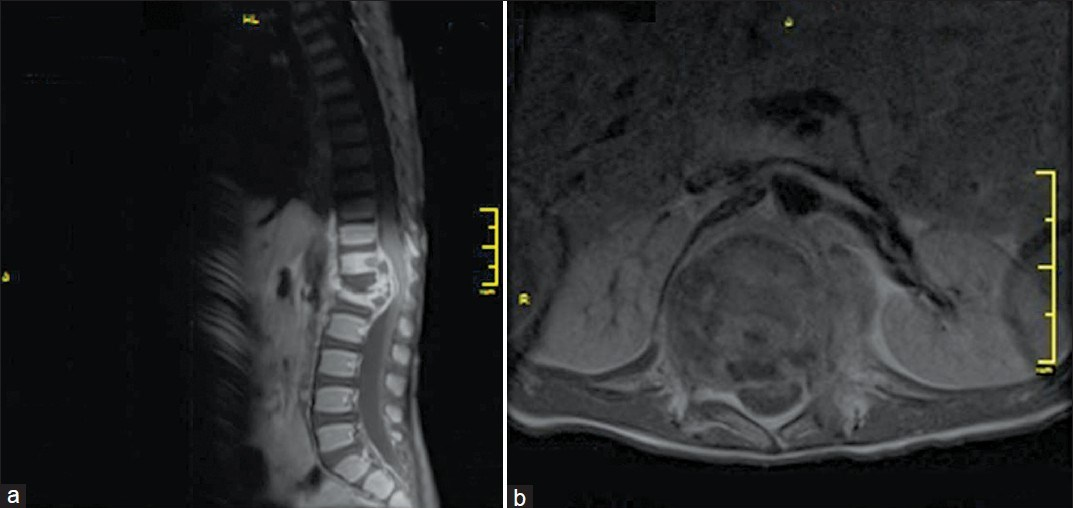

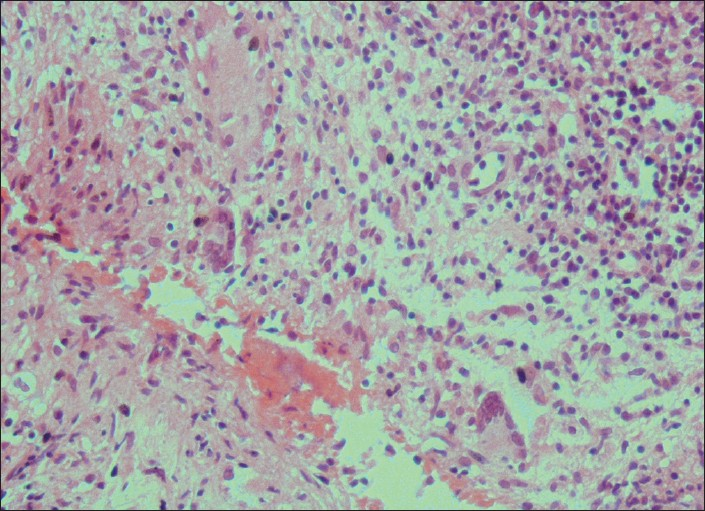

A 3-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital with a 6-month history of gait disturbance and back pain. After spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a tumoral mass at L1 with cord compression, malignancy was suspected, and our oncology department was consulted. His past history was uneventful. There was no known family history of any disease, including exposure to tuberculosis. He had no history of fever, significant weight loss, or night sweats. On physical examination he had back pain and tenderness of the paravertebral region from L1 to L3. Neurological examination showed grade 3/5 motor weakness in the lower extremities, hyperalgesia below the level of L1 vertebra, hyporeflexia of deep tendon reflexes on the lower extremities. Laboratory examination revealed mild anemia and a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (36 mm/h). Chest X-ray was unremarkable. X-ray of the spine showed destruction of the L1 vertebral body and angulation of the lumbar region [Figure 1]. Spinal MRI revealed a destructive mass at the level of the L1 vertebra with soft tissue infiltration and compression of the spinal cord [Figures 2a and b]. On suspicion of malignancy, the patient underwent an open surgical biopsy. During surgery, a seropurulent fluid was discharged and sent for microbiological examination. Microscopic examination for acid-fast bacilli, via staining, and culture for tuberculosis were negative. For culture incubation Löwenstein Jensen medium was used for 21 days. Pathologic examination revealed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation composed of epithelioid cells, lymphocytes, and Langhan's giant cells; consistent with tuberculosis [Figure 3].

- Lateral X ray of the lumbar spine showing destruction of L1 vertebra corpus and kyphosis

- Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in sagital and axial slices after injection of Godolinium (a) destructive mass at the level of L1 vertebra with soft tissue infiltration (b) L1 spondylitis causing kyphosis and compression of the cauda equina

- Histopathologic examination showing granulomatous inflamation with caseous material

The purified protein derivative (PPD) test was 14 -15 mm. positive. The patient was administered four-drug chemotherapy (isoniazid 15 mg/kg; rifampicin 10 mg/kg; pirazinamide 30 mg/kg and streptomycin 20 mg/kg) for 2 months. After 4 weeks of four-drug antituberculosis therapy, the symptoms improved, and he gained weight. When a detailed family history was taken again, we realized that his grandfather had been diagnosed with tuberculosis. We referred him to the neurosurgery clinic for spinal surgical treatment. We administered four-drug treatment for 2 months and planned to continue antituberculosis treatment with two drugs for 1 year.

DISCUSSION

Tuberculosis is still an important infectious disease in many parts of the world, including Turkey. It has been reported that 9.2 million new cases of tuberculosis were diagnosed worldwide in the year 2006.[13] It is known that tuberculosis can mimic several different clinical pictures.[4–7] Therefore, it is very important that clinicians increase their awareness of tuberculosis and characteristic manifestations. Pott's disease represents the most common form of spinal tuberculosis.[8] Tuberculous spondylitis usually presents as mass lesions with little evidence of systemic illness. Extension of the infection from the vertebrae into the adjacent soft tissue to form paravertebral or epidural masses is commonly observed. Spinal tuberculosis in children commonly affects the dorsolumbar spine. Benzagmout et al, reported that, in their study, the most commonly infected area was the lumbar spine.[9] Similarly, in our case, the affected vertebra was L1. The clinical symptoms of spinal tuberculosis are usually insidious, such as back pain, fever, paraparesis, sensory disturbance, and bladder dysfunction. All these symptoms may be interpreted as stemming from an underlying paravertebral mass. Among the types of vertebral osteomyelitis, a relatively longer mean diagnostic delay is observed in spinal tuberculosis. Since the signs and symptoms are not specific, this disease may be easily misdiagnosed as other disorders. In the majority of cases, the diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis was confirmed by radiological characteristic findings after clinical suspicion. The diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis on MRI depends on the presence of paravertebral abscess and the involvement of contiguous vertebrae and intervening discks.[8] But MRI findings may not be sufficiently diagnostic for tuberculosis in some cases. Pathological examination is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis. Huang et al, reported a case of primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma originating from a lumbar vertebra that was initially misdiagnosed as tuberculous spondylitis.[4] They reported that radiological and clinical examination led them to the diagnosis of spinal tbc, and they treated their patient with antituberculous therapy. However, after failing to respond to antituberculous therapy, their patient underwent spinal cord decompression and lesion biopsy, and was finally diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Paravertebral masses may occur as a result of benign or malignant tumors. Common primary paravertebral tumors in children include neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Güne° et al , in a study of 28 children with primary paravertebral tumors, reported that the majority of tumor diagnoses were neuroblastoma (46.4 %), and soft tissue sarcoma (35.7%).[10] Because a variety of unusual lesions have radiological features similar to paravertebral tumors, in the case of a paravertebral mass, a diagnosis other than malignant tumor should be considered, including tuberculosis, especially in endemic areas. In conclusion, this case highlights the importance of being aware that spinal tuberculosis has many different radiographic features and can mimic a spinal malignancy. In order to avoid delayed diagnosis, pediatricians and radiologists must be aware of spinal tuberculosis, which may interfere with other clinical conditions.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Species distribution of theMycobacterium tuberculosis complex in clinical isolates from 2007 to 2010 in Turkey: a prospective study. J clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3837-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO report 2008: Global tuberculosis control: Surveillance, planning, financing. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the lumbar vertebrae mimicking tuberculous spondylitis: A case report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:1621-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tuberculoma of the cervical spinal canal mimicking en plaque meningioma. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:197-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of spinal infection and malignancy. J Neuroimaging. 2005;15:164-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- The usefulness of CT perfusion in differentiation between neoplastic and tuberculous disease of the spine. J Neuroimaging. 2009;19:132-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Noncontiguous spinal tuberculosis: Incidence and management. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:1096-0.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paravertebral malignant tumors of childhood: Analysis of 28 pediatric patients. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:63-9.

- [Google Scholar]